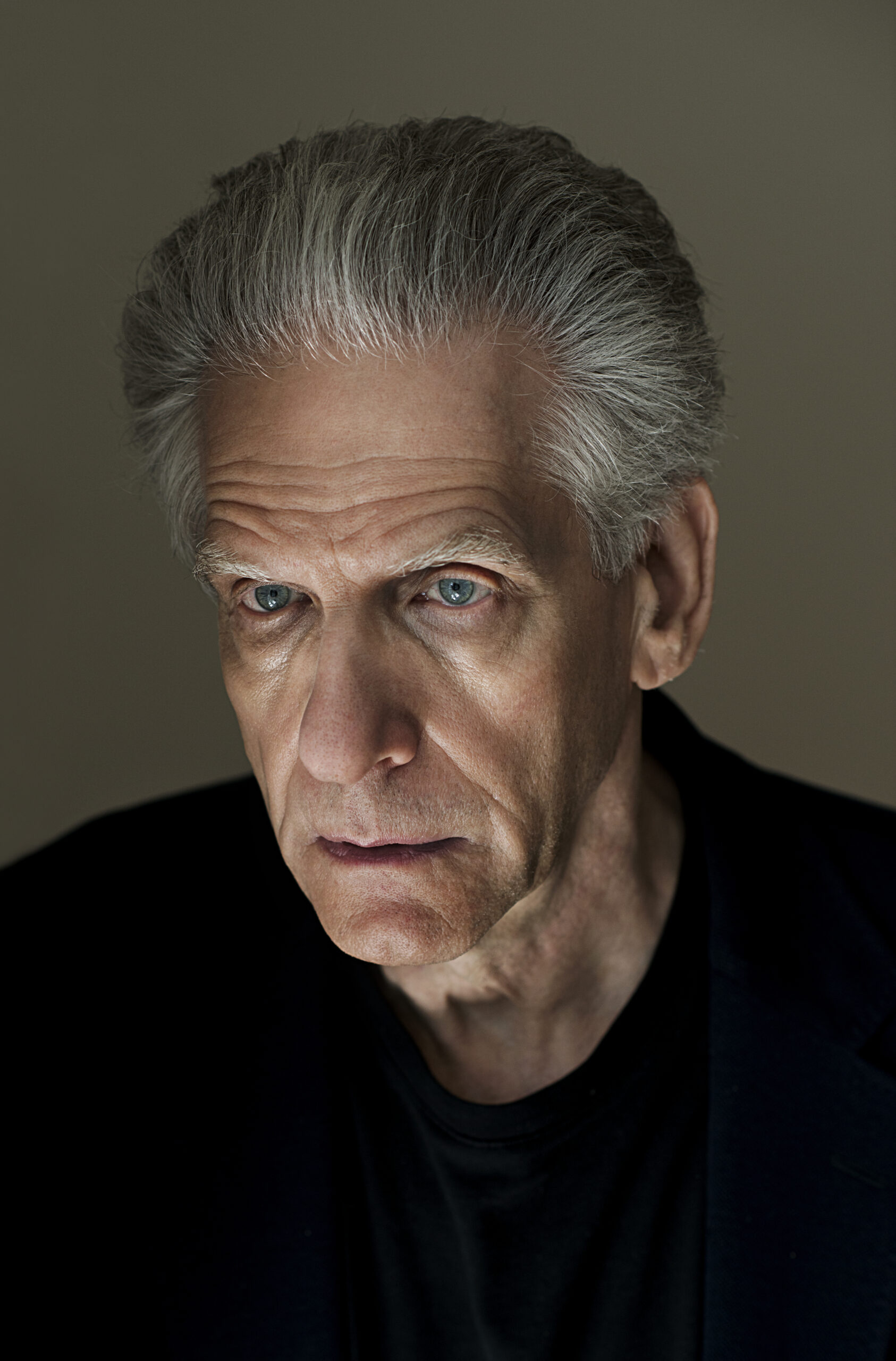

There’s No Catharsis: David Cronenberg on “The Shrouds”

An interview with the legend about his latest film, The Shrouds.

The latest film by David Cronenberg is his most personal in decades. Written after the death of his wife of 43 years, it’s about the unending nature of grief, the strange ways that people suffer, and what truth constitutes in a world of endless, meaningless possibilities.

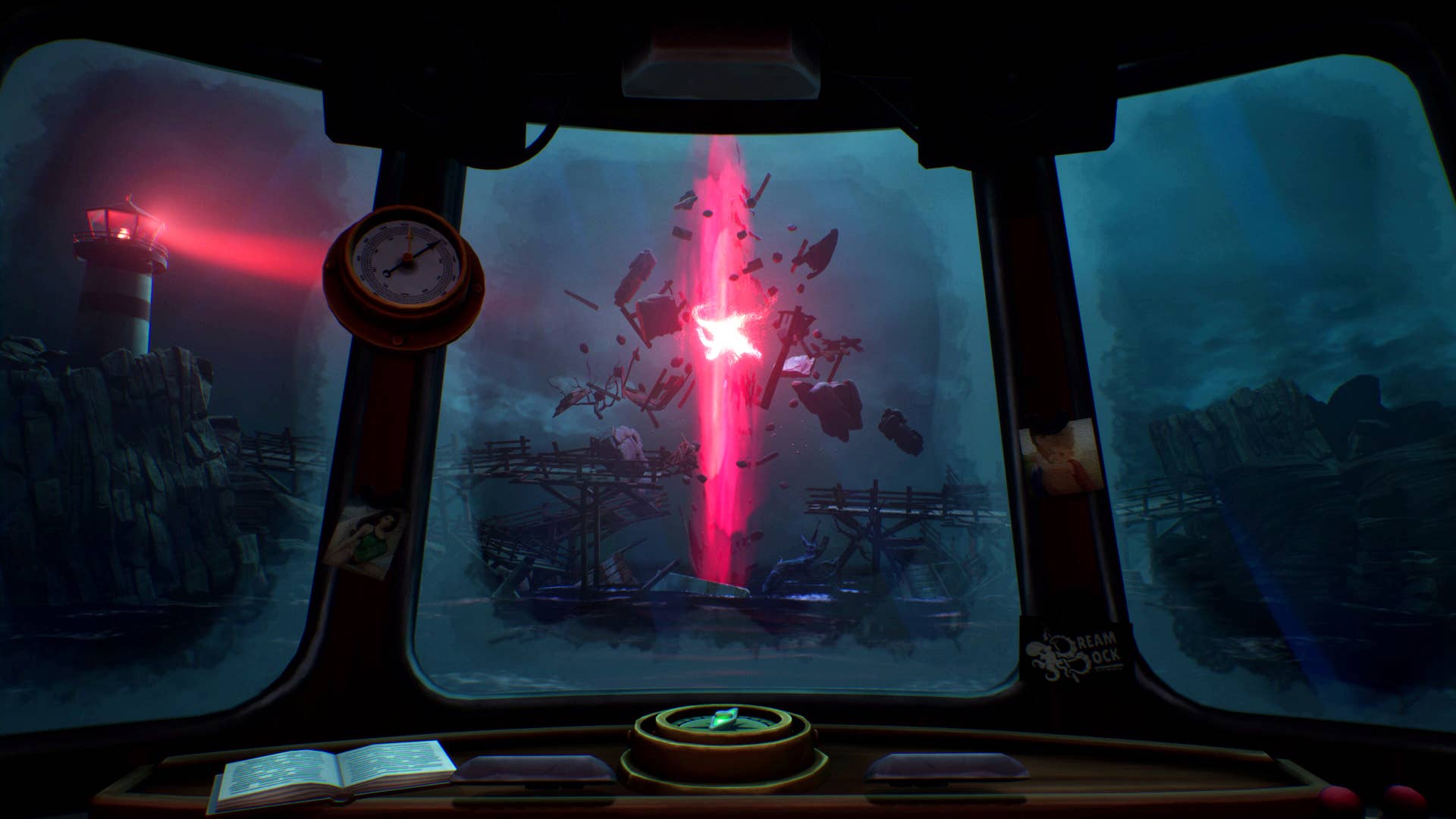

In “The Shrouds” (in theaters April 18), an entrepreneur named Karsh (Vincent Cassel) has designed a high-tech burial shroud, equipped with cameras, that allows the bereaved to watch the bodies of their loved ones decomposing in real time. Karsh was moved to create this technology, which he calls GraveTech, by the loss of his wife, Becca (Diane Kruger), after a debilitating illness. That he can’t bring himself to move on is a frequent topic of conversation with Becca’s twin sister, Terry (also Kruger), with Terry’s ex-husband, Maury (Guy Pearce), and with the AI assistant (voiced by Kruger) upon which he’s become increasingly dependent.

After one of the cemeteries is vandalized, with Becca’s grave among those desecrated, Karsh attempts to investigate, though tracking down those responsible—with Icelandic eco-terrorists, Chinese corporations, and nefarious doctors in the mix, there’s no shortage of suspects—turns out to be more difficult than expected. At the same time, he’s trying to date again, embarking on a relationship with a blind woman (Sandrine Holt) whose terminally ill husband stands to invest in GraveTech.

“You’ve made a career out of bodies,” a character tells Karsh at one point, and it’s separately fascinating to read “The Shrouds” as Cronenberg reflecting on his career-long interest in both matters of the flesh and his characters’ amorphous insides. With a shock of white hair and a European accent that’s amusingly askew in the film’s Toronto setting (shot in mournfully mundane shades of gray by cinematographer Douglas Koch, who also lensed “Crimes of the Future”), Cassel makes for a particularly intriguing director stand-in.

Even as it explores burial rites and mourning phases, there’s a metastatic quality to “The Shrouds,” in that it starts out as a meditation on grief but gradually spreads from there into a more unsettling, peculiar, and morbidly funny vision of dystopia. From his central concept of burial shrouds that perhaps misleadingly intimate the same closeness their digital connectivity only allows from a distance, Cronenberg extrapolates a near-future in which his characters’ confusion and paranoia is sustained and often justified by artificially simulated images and the multitude of untrustworthy screens they’re presented through.

At last fall’s New York Film Festival, where “The Shrouds” screened as a Main Slate selection, Cronenberg spoke with RogerEbert.com about why art is not therapy, how the body is reality, and what conspiratorial thinking has to offer for those in search of comfort and closure.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

It’s a pleasure to speak with you today. I saw “The Shrouds” for the first time at Cannes, and I had an opportunity to do so again at the NYFF screening. I mention that because, with this audience more than the Cannes audience, people were laughing throughout. This is a moving film, but it’s also a very funny one.

Thank you. As you know, in Cannes, there weren’t so many laughs. There were probably more laughs here than in Cannes, because of the language barrier. I think people are afraid to laugh at Cannes sometimes, as well. It’s so powerful; the venue has this glitz and glamor. They laughed more at the Toronto International Film Festival, for example, and I’m sure they did here as well. They get the jokes better.

“Crimes of the Future” ends with this extraordinary shot, impossibly close to Viggo Mortensen’s face, that evokes “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” by Carl Theodor Dreyer: gaze cast upward, eyes far away, a single tear rolling down his cheek. One of the first shots in “The Shrouds,” of Vincent Cassel in the grave with his wife’s corpse, bearing witness to her body’s deterioration, reminded me just as directly of the out-of-body experience of the coffin viewing in “Vampyr,” the film Dreyer made next.

I can see why you connect those moments. I can’t say it was inspired by “Vampyr,” or anything like that, in this case, but that moment was the first one I wrote. What inspired me was this sense of the Jewish philosophy of the soul and the body. I can’t tell you what else inspired me, other than that it came to me that he would be dreaming, and he would be seeing that, and that he would be under a dentist’s anesthetic. I don’t know where it came from beyond that; I can’t tell you.

It’s a powerful moment: this intimate but still essentially abstract access that Karsh has gained, through the shrouds, brings him no catharsis. It only prolongs pain.

It’s the same for me and my film. I wouldn’t say that it prolongs the pain; it just acknowledges it. To me, art is not therapy, and there’s no catharsis. It’s not cathartic to do something like this film, for me. I can tell you an anecdote: an Italian psychiatrist came to my house in Toronto to talk to me because he liked to write about films from the psychiatric point of view. And one of the things he said was, “How are you dealing with your loss?” I said, “Well, I’m suffering. That’s how I’m dealing with it.” And he said, “Oh, I don’t think you need any therapy.” [laughs]

Because that’s the reality: you will suffer, and it won’t go away. Doing the movie was more because, as an artist, you tend to shape your experience of life into some kind of art, and that’s your impulse to do that. But, as I say, it’s not for catharsis, and it’s not for therapy. I mean, listen, if there’s some sculptor or painter who said, “No, what I do is therapy,” fine. I’m not going to argue. But for me, I don’t see art as being that; it’s something else. I’m the same as Karsh. You’re looking at it, but that doesn’t make it less painful.

You come from a secular Jewish background, but Karsh does not. In that first scene, with his date, Karsh refers to himself as a “non-observant atheist” and even suggests that the shroud of Turin might be a fake. “The Shrouds” is a film most concerned with burial rites and customs, so I’m curious about positioning Karsh outside of a chosen faith despite the nature of his work.

It was interesting for me to open with that. As he discusses with his date, it’s all from the point of view of someone who would be religious: not him but, he’s saying, in the Jewish religion, this is what matters. I normally don’t have characters who are driven by religion; it doesn’t really interest me, in general, but in terms of the emotion and situation of the film, it felt right to do that in this film. This was a pretty Jewish film, on many levels.

Down to the Matzoh ball soup and pastrami.

Yes, with corned-beef sandwiches, even.

There’s an absurdity to mourning rituals, as well, in that a certain distance can open up for the observant. This series of cultural and religious expectations can sometimes supplant a more direct, personal, emotional reckoning with grief—as if it’s a screen they’re looking through, which you get at in this film.

But they go together, you know? A lot of the ritual around grief has been developed in order to shape the grief and bring to it a communal understanding, so there’s not just a private grief. Through ritual, you share the grief. And I understand that, from a human point of view. In terms of actually believing in a soul after life? Well, I don’t. But I understand the metaphorical use of that idea. And it’s not just metaphorical; there’s an emotional and a communal understanding that goes with it.

For Karsh, given the commercial potential he seems to see in GraveTech, I found it intriguing to see his grief being shaped by capitalism, outside of other cultures or religions.

Being a capitalist and an entrepreneur is his art. It’s his mode of expression, his way of dealing with the world and engaging with it. For him, it’s a natural thing to do something like GraveTech. It’s not perverse. It’s not dishonorable. It might make money or might not; we don’t get into that. As Maury, his brother-in-law, says, “I’m going to bring down the whole empire.” And Terry says, “There is no empire!” He wants one, maybe, but he hasn’t created it yet. And it’s his version of making the movie. For me, it’s making the movie; for him, it’s making the GraveTech cemetery.

One could say, “you making this movie is you making money from your grief.” If you want to get moralistic about it—although I think it would be rather strange—you could say this film is exploitative, that you’re exploiting the death of your wife. But if you do that, then you have dismantled the whole human enterprise of art. You’ve made art impossible, basically. You’re saying all art is immoral, because it’s always exploitative. And I can see some people being happy to do that—not to get into it, but if you agree with the whole idea in identity politics that you can only create characters who are like you, then there’s no art. It’s over. It’s over.

The shrouds allow people to watch their loved ones decompose—in 8K resolution, even, with the most recent upgrades. This is a film full of screens…

There are a lot of screens, yes, including in the Tesla.

And the reality of what anybody’s being shown—versus what they’re seeing—through screens is in question; the screen is not necessarily bringing you closer to anything other than its own display.

Because it’s a creation. There’s a lot of technology and a lot of creativity on every screen—on those screens, on your phone’s home screen. That leaves a lot of room for other kinds of things to be there between you and what you want to see. A lot of it is great and exciting, and some of it is sinister.

Karsh is alerted, at one point, that Hunny—his animated AI assistant, who resembles both Becca and her sister—is not trustworthy, because she’s not independent and is instead being controlled by somebody hiding behind the image.

What you’re saying is that there’s this ideal of a completely independent AI creature responding to you in a completely independent way, like another human might, and that’s said to be a good thing. That’s the goal. But is it really the goal? And is it really possible? The film’s about all these things.

Many of your films have explored the relationship between the body and the spirit. In following the body after death—through disease and decay—how did you think about the relative presence or absence of the soul in this particular film?

It’s very straightforward, and it’s very existentialist. You’re basically saying that body is reality, taken from “Crimes of the Future.” Body is human reality. It’s the way we understand the Earth, as being all about our neurology and neurological structure. And when the body ends, you end, and that’s it. You’re back to oblivion, where you came from; therefore, there is no afterlife, and there is no point in killing people because of your views of Heaven or some afterlife, though people still do that. That’s basically it.

Karsh is accepting that reality. He’s not going with the dream that you see him in, at first, that there’s a soul fluttering around, and it’s separate from the body. That’s him thinking about the way some people that he knows might think about it, but in his reality, there is nothing, and that’s a fantasy or a delusion, depending on how you look at it. That’s my feeling as an atheist.

I’m not a militant atheist, although, honestly, I think the world would be better off if everybody was an atheist—but maybe I’m wrong about that. It certainly didn’t work very well for the Soviet Union, so whatever. There have been, and still are, some experiments in atheism, and it always ends up being that the state then becomes the religion, and then the martyrs of the state end up being the saints, so you’re really constructing another religion—as in North Korea, for example, or the religion of high tech, where we also have our martyrs.

If the body is reality, can there be anything real in disembodied, digital spaces? There’s a swirl of confusion created by the online interactions in this film, and “The Shrouds” is at its funniest in turning this search for truth and meaning into a full-on conspiracy.

That search is itself a conspiracy, I’m saying. Even if it’s a political conspiracy, it’s empowering you, because you know what’s really going on, so you’re very special. But it’s also giving meaning to some things that are meaningless. And so, in a sense, death is meaningless, and the death of someone young is especially meaningless. Could it really just be the rampages of a single cell that becomes tumors, that becomes cancerous? Is that really what it’s all about? That seems meaningless.

It doesn’t make sense. This entire human being who’s had an entire, complex life is suddenly dead because of that one thing? That can’t be possible. It must be something else. It must be the doctors. It must be the priest. Maybe she was taking some drugs that I didn’t know about. Maybe she was having an affair with some crazy person. It’s all to find a way to deal with the grief, and that’s just one possibility.

One conspiracy theory I’m fond of is dead-internet theory: that bots and algorithms generate most internet content, and organic human interaction is disappearing online.

That it’s all bots talking to bots? Yes: that’s possible. I think humans will still want to interact with other humans, and they’ll find ways to make sure that they’re really doing that, but it’s absolutely the case right now, with deepfakes everywhere. It’s compelling and full of all kinds of possibilities, most of them sort of stupid but some of them quite sinister.

With every form of communication, there have always been people trying to control us through it, with propaganda. What is propaganda? Well, it’s bot stuff, really—a relatively, technologically primitive version of bots. If you look at the history of propaganda, it’s been around forever, and it’s usually sophisticated for whatever time it comes from. Right now, there are more people on Earth, and there’s more ways to reach them than ever before, so it’s kind of working together.

I’d asked about Dreyer earlier, but I was curious as well to ask about Alfred Hitchcock’s place among your influences, given what I saw reflected of “Vertigo” in Karsh’s relationship with Becca’s twin sister, really with all three of Diane Kruger’s characters.

I mean, I love Hitchcock, and I enjoy his presence as a character as well as a filmmaker. And he made many wonderful films, and he was a really entertaining guy. And I think the way he talked about filmmaking, he was being a little bit naughty in what he was saying, because I think that it was a lot more art, spontaneity, and personality at play, in that he wasn’t just the puppet master manipulating the audience, which is the way he liked to play it. I think there was a lot of himself in that.

For me, it’s not like De Palma, who really specifically worshipped him and modeled himself around his structures. I don’t say this as a matter of humble bragging, but I really took my creative inspiration from literature more than movies, even though I loved movies and saw everything, from cowboy movies to you name it, being a kid. I don’t really have a specific guiding spirit when it comes to movies as such.

Obviously, I’m sure I’ve taken tons of stuff from everybody. I don’t normally think of myself as taking anything from Hitchcock, but there’s a moment in “Vertigo” where I remember thinking, “This makes no psychological sense, whatsoever.” James Stewart is dressing Kim Novak as his wife, and he says, “Surely, it can’t matter to you.” [laughs] And I said, “I don’t think there’s any woman who it wouldn’t matter to,” you know? You’re dressing me up to look like your dead wife. I mean, really. I thought that was a bit of structural manipulation but not very realistic; even as a kid, when I saw the movie, I didn’t buy that. I thought, “She’s gotta say no!” [laughs]

This reminds me of the catastrophic date Karsh takes this woman on, to the restaurant that adjoins the cemetery where his wife is buried. There’s this projection of his complex of grief over all the other characters on screen. It feels like we’re inside his headspace, looking out.

Although I do like Maury, because Maury has some things going on. And, honestly, if you asked Diane Kruger, she would say it’s Terry, because she had a lot of fun playing with Terry, who was sort of outrageous. But it is a Karsh-focused story; it is, in that sense, a first-person movie. But I don’t think about that, honestly. I let the characters wrestle with each other as they can.

I’ve had a couple of movies with women as protagonists, like “eXistenZ,” for example, and that just seemed like a natural choice for that movie. I distinctly remember not being able to get it to work until I changed the protagonist to a woman. Why that was the case, I have no idea, but I went with it, so it became her first-person story. Once it starts to come alive, I don’t worry about what it is, in that sense, or what its structure is. It tells you when it’s coming alive, and when it’s fighting you and it’s not coming alive.

Is it always easy to see which direction an idea’s going in?

Once the momentum is there, I don’t recall really wrestling in that way, where it’s fighting me to the death. You get past a certain point, and it just starts to flow. You go back and forth. It’s never completely linear. But I haven’t had that problem.

How did you end up with Vincent Cassel in the lead role, and what do you make of those who’ve said that he looks like you—or that he was styled to resemble you?

As I have jokingly—but honestly—said, I didn’t cast him for his hair. I’ve always said that casting is a black art, and there’s a lot that goes into it—including whose passport is involved, because it’s an international co-production, and that you can’t have everybody you want, for obvious reasons. They might not want to do it, they might be too expensive, and they might not be available. I considered a lot of people before I ended up with Vincent. It wasn’t really, “Let’s find somebody who looks like me,” because I frankly do not think that Vincent looks at all like me, right?

Well…

The hair, maybe, a little bit. Unbelievable as it might seem to some people, it never occurred to me that he was looking anything like me, frankly.

It creates this inability to fully grip the character, I think, because there’s that slight resonance of resemblance.

That’s true. And that’s, first of all, because I wrote it that way, though I’m not an entrepreneur, and I don’t own a restaurant or a cemetery, and I would not be very good at it if I did. But I did say to Vincent—although I knew he would have an accent—to basically use me as a model for speaking, because this is a Toronto movie, and these people are from midtown Toronto. That’s where I’m from, and that’s where my accent comes from.

“As you try to dampen your French accent a little bit and make it a little more Canadian,” I told him, “use me as a model.” I said the same to Diane, actually, and she was very good at it. And one of the things that he did was slow down his speech, because he’s usually very rapid-fire in French, and his French movies are very quick and staccato. He wanted to be “more chill,” as he said that’s what he thinks I am. He should only know.

He would chill it down and be a little more relaxed in his speech. It wasn’t just the accent, but it’s the rhythm of speech, and I can see why that would make people think even more that he was my surrogate. And that’s okay. The fact that some of the dialogue in the movie has come from my life right to the screen, and that its initiation was because of my wife’s death, doesn’t make it a good movie automatically, just because it’s based on real life. That’s just the beginning. In a way, it’s irrelevant.

I know it’s of interest to people who read about it, but for people who have no idea who I am, have never met me, and don’t know what I look like, the movie has to work. The characters have to be alive on their own. They can’t take anything from me into it, so it’s not really an added value.

“The Shrouds” opens in U.S. theaters April 18, via Janus and Sideshow.

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)