Inside the academic conference taking Terrifier back to school

A forthcoming conference seeks to position the ultraviolent horror franchise within academia – what might we learn from Art the Clown? The post Inside the academic conference taking Terrifier back to school appeared first on Little White Lies.

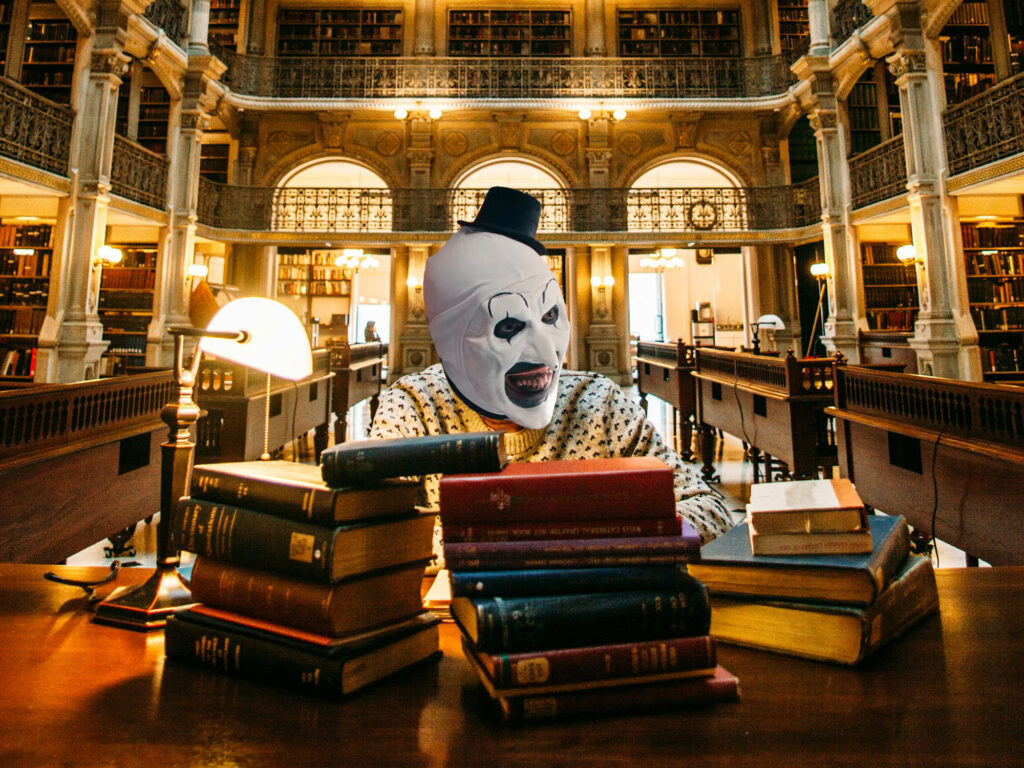

While the typical academic film conference might unpick the oeuvres of Robert Bresson or Chantal Akerman, film scholar Dr Reece Goodall and historian Dr Hannah Straw are gathering the world’s finest in May to paint the hallowed halls of Warwick University with blood (figuratively speaking of course). This spring, they’re presenting the world’s first Terrifier Conference: a contrarian academic assembly discussing Damien Leone’s titular gore-sploitation clown-based franchise.

The franchise’s gratuitous violence is hard to digest, but Goodall and Straw are encouraging film studies’ brightest to get stuck in. Brutality as art, cinematic afterlives on TikTok and takes on franchise figurehead Art the Clown (an anti-Chaplin sadist responsible for Terrifier’s brutal kills) are just some of the many scalpelled approaches the conference will take to Leone’s axe-swinging corpus. “We aren’t doing anything stuffy and formal,” assures Goodall. Straw concurs: “We just wanted to bring everyone together to talk about [Terrifier]; you don’t have to love it or hate it.”

While Leone’s stomach-churning films are the main focus of the conference, there is a secondary operation at play, one allowing academics to shed their proverbial tweed blazers and seriously address typically shrugged-off ‘low art’. As much as it is about the Terrifier franchise, the conference is also about asking how, and not why, ‘trash cinema’ should be studied, raising questions about how value is attributed to art within academia.

Trash studies seems like a contemporary scholarly pursuit, but academics have examined the bottom of the cinematic barrel since the ‘90s. When Jeffrey Sconce’s essay ‘Trashing the Academy’ strutted onto campus in 1995, it ushered in what lecturer Dr Iain Robert Smith describes as “a generation of PhD students that were really invested in cult and trash cinema”. Thanks to Sconce’s survey of para-cineastes – those rejecting elitist high arts – the field of academia was split open. “It was no longer a divide between art cinema and popular,” explains Smith, “Cult was this new area.”

Operating on a level miles from the accepted film studies canon, yet working under the auspices of its terminology, trash cinema studies corrupts the foundations of cultural value on which the field is built. Case in point, if Damien Leone and Yasujirō Ozu can both be auteurs, then what is the value of that label? Further still, how is that value ascribed? Straw says, “In history, we are a bit more reluctant to study things that are considered – I hate this word – unimportant. So I’ve always been really interested in the history of what people think is trashy and what people think is gossip and not worthwhile.” Studying trash is the ideal site for interrogating what and why certain art is deemed unimportant, opening opportunities for reconsiderations of once-repugnant work as underground, art house and beyond.

Of course, putting trash under the microscope smooths its rough edges. The pope of trash, John Waters, has always been baffled by academic responses to his work, writing in ‘Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste’, “I hate message movies and pride myself on the fact that my work has no socially redeeming value.” Yet Pink Flamingos is enshrined in the Criterion Collection and is hailed as a landmark piece of queer cinema. Giallo mastermind Dario Argento demonstrates a similar mutation, as demonstrated in the recent retrospective of the once controversial creative at the BFI. Partially thanks to scholarly reappraisals, the pot-infused aura of irreverence once synonymous with trash is less pungent. “Loads of people say that cult cinema is dead,” says Smith, citing the internet and a recent uptake of interest in horror as also contributing to a decline in academic interest.

This is why the Terrifier conference is an interesting anomaly. Just when trash scholars are hanging up their mortarboards, making way for Tumblr-mods-cum-academics, Goodall and Straw hope to prove that there are new tricks to learn from this old dog. “The question really is, what questions should we be asking about the works that we engage with, and that’s something that all our fields are still grappling with,” observes Goodall. Instead of blowing hot air debating the worth of a film, this conference is aiming for the jugular, interrogating the perverse pleasures of trash within the film’s boundaries.

Asked if anything is off the cards for study, Goodall immediately stands firm on the value of low art: “If we ask the right questions of things we look at, we are going to come up with many interesting, insightful things about ourselves and the world that we live in and the culture that we engage with.” Consider that Terrifier 3 took 45 times its budget at the box office, opera and theatre are struggling to put bums on seats, and that many upstart cineastes are cutting their teeth on YouTube, TikTok, and Letterboxd to avoid tuition fees. While social media will never substitute for a lecture, and the eye-watering fees making academia unreachable for many aren’t getting smaller, this conference does demonstrate that the elitist boundaries which once designated the treasure from the trash aren’t informing today’s tastemakers. It’s as John Waters said: “To understand bad taste, one must have very good taste.” Who would dare disagree with the pope himself?

The post Inside the academic conference taking Terrifier back to school appeared first on Little White Lies.

![‘Haruki Murakami Manga Stories Vol. 3’ Gives Foreboding Fiction a Macabre Makeover [Review]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Haruki-Murakami-Manga-Stories-Vol-3-Car-Attack.jpg?fit=1400%2C700&ssl=1)

.png?format=1500w#)

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)