The Heyday of Horror Hotlines and Why We Still Love to Fear the Phone

It’s no accident Freddy Krueger is the most famous monster of the last 50 years. He craves the spotlight. Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, Leatherface—those killers operate in the shadows. They hide their faces, dispatch their victims quickly, and don’t speak. But Freddy is an exhibitionist. Each kill in the Nightmare on Elm Street saga is an elaborate production of Freddy’s design. His kills are performances, right down to working out his new comedy material—which is really its own form of torture. Forget the souls of children, Freddy is hungry for attention. Which, by the way, is a hunger just as depraved. (Trust me; I’m an unemployed actor.) It’s no surprise his most memorable line, from 1987’s Dream Warriors, remains “WELCOME TO PRIMETIME, BITCH.” Sometime around the 1989 release of The Dream Child, Freddy’s exhibitionism escaped into the real world in the form of endless Nightmare on Elm Street merch. There were Freddy t-shirts and Freddy jean jackets. A tie-in board game and a “Talking Freddy” doll that wished you “pleasant dreams” when you pulled a string on his back. You could join the Freddy Fan Club or read a novel from his YA series. Watch the syndicated TV show Freddy hosted, or listen to songs about Freddy from four—four!—Grammy-nominated artists. Krueger eerily gained in real life the omnipresent power he possessed in his movies, living forever in teenagers’ minds, moving from one trend to the next, powered by something more sinister than dark magic: marketing. So of course Freddy would capitalize on one of his decade’s definitive devices: the telephone. In the late 1980s you could communicate with Krueger on your home phone (after you “get your parents’ permission,” of course) through the awesome telecommunicative power of the hotline. Dialing 1-900-909-FRED connected brave teens to a running tape of short ghost stories, each introduced by Freddy Krueger like a malevolent MTV VJ throwing to Paula Abdul videos…HAHAHAHAHAHAHA. IT’S TIME FOR ANOTHER ONE OF FREDDY’S FAVORITE BEDTIME STORIES. AND THIS ONE’S A DREAM—MY KIND OF DREAM: THE KIND YOU DON’T WAKE UP FROM… You can listen to 40 consecutive minutes of this stuff on YouTube, thanks to some intrepid young Gen-Xer who owned a tape deck and I guess was willing to catch hell from their parents when the phone bill arrived. The phone-a-Freddy number is just one example of the “horror hotline,” itself a spooky subgenre of the 900-number boom. Nine-hundred numbers—or phone services that charged callers by the minute—weren’t exclusive to horror. On the contrary, you could find a hotline for just about anything you wanted, from sports scores to video game tips to religious sermons to a phone number that simply gave you compliments (1-900-EGO-LIFT). “When you think about it, in the late ’80s, there was no way to find out what the weather was in California if you were in New York,” industry expert Rick Parkhill told Fast Company in 2015, “unless you called somebody, or turned the television on and waited for something to happen.” The Los Angeles Times even dubbed hotlines “the fourth medium.” Indeed, 900 numbers were an early beacon of the global marketplace made possible through technology’s miraculous potential.(Rolls eyes.) Yes, the biggest ones were sex stuff. The low overhead required, combined with the lax regulation of a new industry, turned the 1980s hotline business into a neon-colored gold rush. It was the decade’s biggest telecom innovation since the see-through phone. By 1993, over 10,000 pay-per-minute hotlines were operating, according to Priceonomics, earning nearly a billion dollars per year. That’s a lot of parentally approved minutes. One former hotline businesswoman called it “the wild west.” Horror hotlines also brought home (literally) the long relationship between phones and fear. As it always has, horror thrived in such a shadowy landscape. Freddy’s 900 numbers were joined by other hotlines offering creepy audio, like 1-900-660-FEAR and 1-900-909-EVIL. Some were similar to Freddy’s ghost story service. Other 900 numbers were more creative with the technology. Ads for 1-900-490-DEAD promised to connect callers to “the phone zombies” and a chance to speak to one live (as “live” as zombies can be, anyway), 1-900-900-DARE gave your “horror-scope,” and on “Creep Phone” (“THE PHONE NUMBER NIGHTMARES ARE MADE OF”) you could record your own “screaming monster message” to be broadcast to “millions” of other “monsters and madmen,” which basically sounds like a precursor to Twitter. Some horror hotlines even served as an early interactive marketing tool for scary movies. In TV spots for Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers, fans were challenged to “Save Michael’s Next Victim,” a kind-of dial-your-own-adventure where the caller ran for their life through Haddonfield for $2 per minute. Whatever their particular paranormal service, these hotlines were usually produced under the same lo-fi conditions as our favorite horror

It’s no accident Freddy Krueger is the most famous monster of the last 50 years. He craves the spotlight. Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, Leatherface—those killers operate in the shadows. They hide their faces, dispatch their victims quickly, and don’t speak. But Freddy is an exhibitionist. Each kill in the Nightmare on Elm Street saga is an elaborate production of Freddy’s design. His kills are performances, right down to working out his new comedy material—which is really its own form of torture. Forget the souls of children, Freddy is hungry for attention. Which, by the way, is a hunger just as depraved. (Trust me; I’m an unemployed actor.) It’s no surprise his most memorable line, from 1987’s Dream Warriors, remains “WELCOME TO PRIMETIME, BITCH.”

Sometime around the 1989 release of The Dream Child, Freddy’s exhibitionism escaped into the real world in the form of endless Nightmare on Elm Street merch. There were Freddy t-shirts and Freddy jean jackets. A tie-in board game and a “Talking Freddy” doll that wished you “pleasant dreams” when you pulled a string on his back. You could join the Freddy Fan Club or read a novel from his YA series. Watch the syndicated TV show Freddy hosted, or listen to songs about Freddy from four—four!—Grammy-nominated artists. Krueger eerily gained in real life the omnipresent power he possessed in his movies, living forever in teenagers’ minds, moving from one trend to the next, powered by something more sinister than dark magic: marketing.

So of course Freddy would capitalize on one of his decade’s definitive devices: the telephone. In the late 1980s you could communicate with Krueger on your home phone (after you “get your parents’ permission,” of course) through the awesome telecommunicative power of the hotline. Dialing 1-900-909-FRED connected brave teens to a running tape of short ghost stories, each introduced by Freddy Krueger like a malevolent MTV VJ throwing to Paula Abdul videos…

HAHAHAHAHAHAHA. IT’S TIME FOR ANOTHER ONE OF FREDDY’S FAVORITE BEDTIME STORIES. AND THIS ONE’S A DREAM—MY KIND OF DREAM: THE KIND YOU DON’T WAKE UP FROM…

You can listen to 40 consecutive minutes of this stuff on YouTube, thanks to some intrepid young Gen-Xer who owned a tape deck and I guess was willing to catch hell from their parents when the phone bill arrived.

The phone-a-Freddy number is just one example of the “horror hotline,” itself a spooky subgenre of the 900-number boom. Nine-hundred numbers—or phone services that charged callers by the minute—weren’t exclusive to horror. On the contrary, you could find a hotline for just about anything you wanted, from sports scores to video game tips to religious sermons to a phone number that simply gave you compliments (1-900-EGO-LIFT). “When you think about it, in the late ’80s, there was no way to find out what the weather was in California if you were in New York,” industry expert Rick Parkhill told Fast Company in 2015, “unless you called somebody, or turned the television on and waited for something to happen.” The Los Angeles Times even dubbed hotlines “the fourth medium.” Indeed, 900 numbers were an early beacon of the global marketplace made possible through technology’s miraculous potential.

(Rolls eyes.) Yes, the biggest ones were sex stuff.

The low overhead required, combined with the lax regulation of a new industry, turned the 1980s hotline business into a neon-colored gold rush. It was the decade’s biggest telecom innovation since the see-through phone. By 1993, over 10,000 pay-per-minute hotlines were operating, according to Priceonomics, earning nearly a billion dollars per year. That’s a lot of parentally approved minutes. One former hotline businesswoman called it “the wild west.”

As it always has, horror thrived in such a shadowy landscape. Freddy’s 900 numbers were joined by other hotlines offering creepy audio, like 1-900-660-FEAR and 1-900-909-EVIL. Some were similar to Freddy’s ghost story service. Other 900 numbers were more creative with the technology. Ads for 1-900-490-DEAD promised to connect callers to “the phone zombies” and a chance to speak to one live (as “live” as zombies can be, anyway), 1-900-900-DARE gave your “horror-scope,” and on “Creep Phone” (“THE PHONE NUMBER NIGHTMARES ARE MADE OF”) you could record your own “screaming monster message” to be broadcast to “millions” of other “monsters and madmen,” which basically sounds like a precursor to Twitter. Some horror hotlines even served as an early interactive marketing tool for scary movies. In TV spots for Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers, fans were challenged to “Save Michael’s Next Victim,” a kind-of dial-your-own-adventure where the caller ran for their life through Haddonfield for $2 per minute.

Whatever their particular paranormal service, these hotlines were usually produced under the same lo-fi conditions as our favorite horror movies. The Freddy Krueger 900 number was created by Phone Programs, Inc., whose vice president, Cory Eisner, described a typical production in Fast Company’s story: “It would almost be like old-time radio,” Eisner said. “We would produce these messages in our studio, and it would go for a minute or so depending on which line you were doing.”

The same bonanza that helped elevate such easily produced 900 numbers to nine-figure revenues would eventually cause national drama, as we’ll see. But in their brief existence, horror hotlines provided audiences with a new, intimate kind of fear. They also brought home (literally) the long relationship between phones and fear, and pointed toward a deeper relationship between communication, technology, and the new existential anxieties they’ve unleashed on mankind.

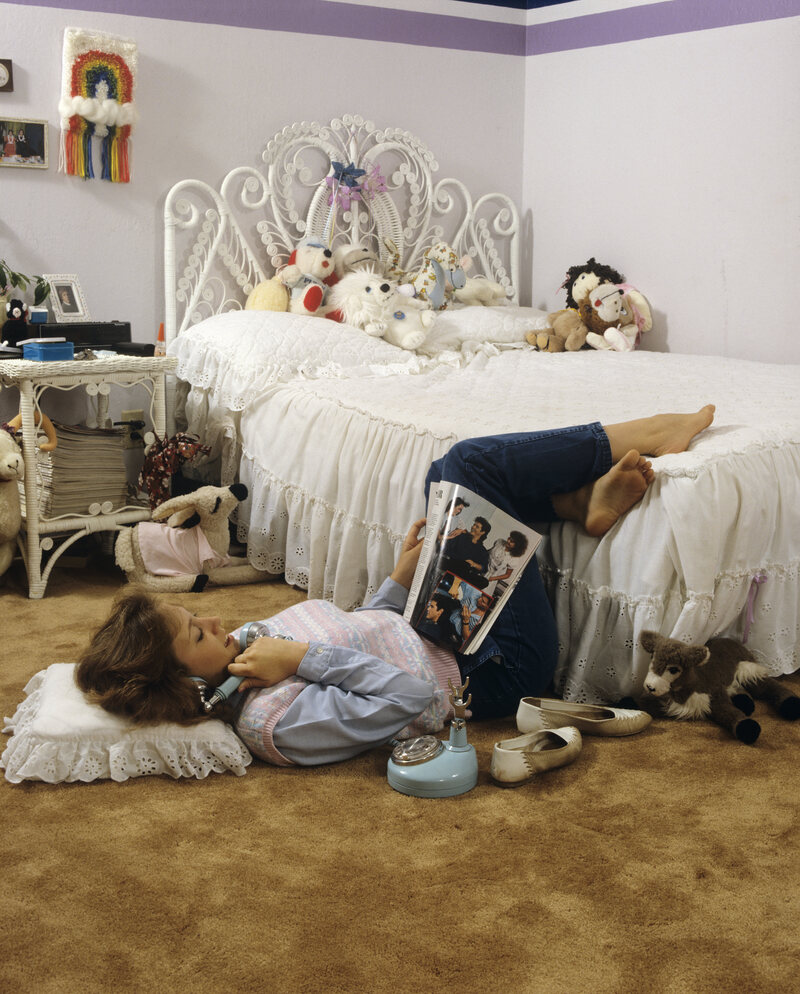

Now, full disclosure: I never actually called any of these numbers. No hotline was as terrifying as what my dad would do to me if he discovered I’d racked up God knows how much in charges calling the Sega Tips & Tricks hotline (1-900-200-SEGA) because I couldn’t beat Golden Axe. But I suspect my friends had similar financial limitations: We all sucked at Golden Axe. In fact, I think this was true for many of us, and that society’s recollection of hotlines are not memories of the hotlines themselves but the commercials for those hotlines. It’s like some New Wave remix of the Mandela effect.

But those ads are no less revealing. For example, an unsettling trait shared by nearly all horror hotline commercials was intimacy. “I’m closer than you think,” says Freddy in one of his ads. “Just a phone call away.” And the zombies of 1-900-490-DEAD, its ad warned, were “in the phone, and they’ve got your number!” My personal favorite, however, is the bizarre and frantic 10-second spot for 1-900-660-UGLY:

“The night holds terror too horrible to be seen. You think you’re safe all alone in your nice, warm house? Well, look outside: It’s outside your door, and it’s coming to take you away to a JOURNEY INTO TERROR!!!”

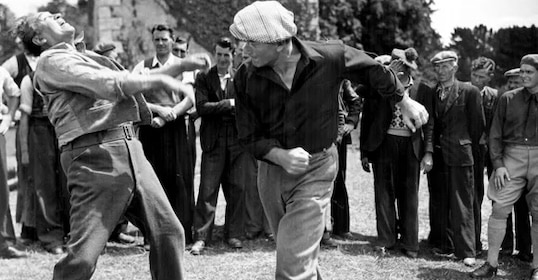

This thing is remarkable for two reasons: (1) The ad helps establish hotlines as a 1980s phenomenon, since its announcer is clearly on cocaine. (2) It played on audiences’ preconceived fear of telephone calls, established by their malevolent role across decades of horror films. With its ability to disguise a caller’s identity and location, the telephone is a useful device for suspense. This led to what critic Marc Olivier has dubbed the “home-alone-with-a-phone” horror subgenre, including such formative slashers as Black Christmas (1974) and Halloween (1978). A 2020 Rue Morgue essay by Chad Collins reminds us that these movies are themselves likely inspired by the urban legend of “The Babysitter,” in which a harassed teenager is told “the calls are coming from inside the house.” (This premise is also, of course, exactly what happens to a young Carol Kane in the opening of 1979’s When a Stranger Calls.) “‘The Babysitter,’” Collins writes, “and by extension Clark’s Black Christmas, recounts the story of young women, within the domestic sphere, receiving menacing phone calls.” And it’s proved a timeless fear. The Scream franchise is the ultimate ode to horror conventions, and what is the first image in the series we ever see? A telephone.

But this bloody knife cuts both ways. As the philosopher Marshall McLuhan has been quoted as saying, “We shape our tools, and our tools shape us.” Yes, phones scared us because of how they were used in horror films, but they were also, I believe, in horror films in the first place because phones are inherently unsettling. Many of the electronic age’s invisible powers seemed mysterious to the average American at first, but phones in particular must have had a radical impact on our perception of reality. Phone communication is so commonplace today that it is impossible to fully appreciate what a phenomenal shift it was when, after 300,000 thousand years of face-to-face contact, homo sapiens could suddenly have real-time conversations with a distant and disembodied voice. What did we even have to compare it to? Hallucinations? The voice of God? Yodeling?

This, the film scholar Alison Wheatley argues, is what first attracted horror creators to phones: “Some of the more grotesque dramatic traditions seized upon the technologies’ potentially disturbing qualities, such as its estrangement of the voice from the body,” she writes in her essay, “Can You Fear Me Now?” Phones, in other words, aren’t just scary because a monster might be on the other end; the phone itself is unsettling. I would even argue this is why so much of the language that evolved around phones has a morbidity to it. Lines “go dead.” Callers get “cut off.” Even their ringing places phones in a grim tradition. To quote Lord Varys from HBO’s Game of Thrones, bells always “ring of horror: a dead king, a city under siege… a wedding.”

Existential techno-fears like these later manifested in Japanese horror films like Suicide Club (2001), Pulse (2001), Uzumaki (2000), and most notably Ringu and its wildly popular American remake (1998 and 2002, respectively). Nina Nesseth cites these movies in her book Nightmare Fuel as stories that “looked at alienation, isolation, and the importance of human connection when all of our communication seems to be mediated by either technologies or consumer products and media.” Long before his hotline, Freddy took this fear to its grossest extreme in the original Nightmare. He doesn’t scare Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) with a phone call, but by turning into the phone—for extra creepiness, he sticks his tongue through the receiver.

Back in the real world, horror hotlines, along with the rest of the industry, enjoyed years of unimpeded popularity. The talent grew bigger, with 900-numbers featuring movie stars like Michael J. Fox, musicians like Prince, and movie-star-musicians like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. At the peak of the WWE’s Golden Era (1982–1993), the league tag-teamed with a hotline studio, corralling icons like Hulk Hogan and Macho Man Randy Savage. “When the wrestlers came out of the ring, their first stop was to be interviewed for the 900 number hotline,” a former CBS advertising associate told Priceonomics. There was even a 900-number award show, the “Golden Telephones.” (I’m not sure which hotline won, but if the show was anything like the Oscars, it probably wasn’t a horror hotline.)

But with 900-numbers’ rising power came chaos. Consumer advocates criticized hotlines’ predatory business practices, like targeting children to make impulsive purchases. (This led to the iconic “get your parents’ permission” caveat.) And the infamous “party” lines made 900-numbers synonymous with sex, outraging the so-called moral majority. On the flip side, according to the L.A. Times, other consumers complained about the hotlines’ “inferior porn.” In 1989, hotline controversy even reached the Supreme Court, with Sandra Day O’Connor and William H. Rehnquist among the majority who found in favor of picking up the phone and dialing NOW. Three years later, however, a new law was upheld that effectively banned adult 900 numbers. These sexy services were, of course, the industry’s biggest earners, and the new regulation would cost hotline companies nearly half a billion dollars that first year. Even the biggest Freddy fan wouldn’t stay on the phone long enough for them to recoup that much loss.

The final blow against hotlines came from the internet. Telephone cords, the hotline’s lifeline, were literally unplugged from touch-tones and switched to modems, making 900 numbers virtually obsolete. But in their relatively short life, hotlines laid some of the cultural and economic groundwork for the very online world that killed them. Pay-per-minute numbers demonstrated people’s demand for instant information in their homes; they proved consumers would pay for that information; and they proved there was no information too strange, obscure, or illicit to find an audience.

Horror hotlines, meanwhile, added a new dimension to the long relationship between our love and our fear of communication. Before they vanished, the horror hotline had one final, glorious, gruesome moment—perhaps its biggest moment: It got a horror film of its own. The 1988 cult classic 976-EVIL had its world premiere in glamorous Los Angeles. It was a sendoff that, however briefly, made 900 numbers a movie star. Naturally, its director was Robert Englund, better known as Freddy Krueger.

![‘Snowtown’ Unpacks the Brutal “Bodies in the Barrels” Case [Murder Made Fiction Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Snowtown-2011.jpeg)

![Lifetime’s ‘Trapped in Her Dorm Room’ Tackles Toxic Male Entitlement [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Trapped-in-Her-Dorm-Room-2025.jpg)

![Bill Skarsgård's Thriller Locked Went Above And Beyond To Maximize Its Primary Location [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/bill-skarsgrds-thriller-locked-went-above-and-beyond-to-maximize-its-primary-location-exclusive/l-intro-1742587986.jpg?#)

![How To Turn An Airline Meal Voucher Into A Starbucks Gift Card—Or Use It To Earn Miles [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/20230619_080120.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)