Revisiting the Bunker: Michael Shannon on “Eric LaRue”

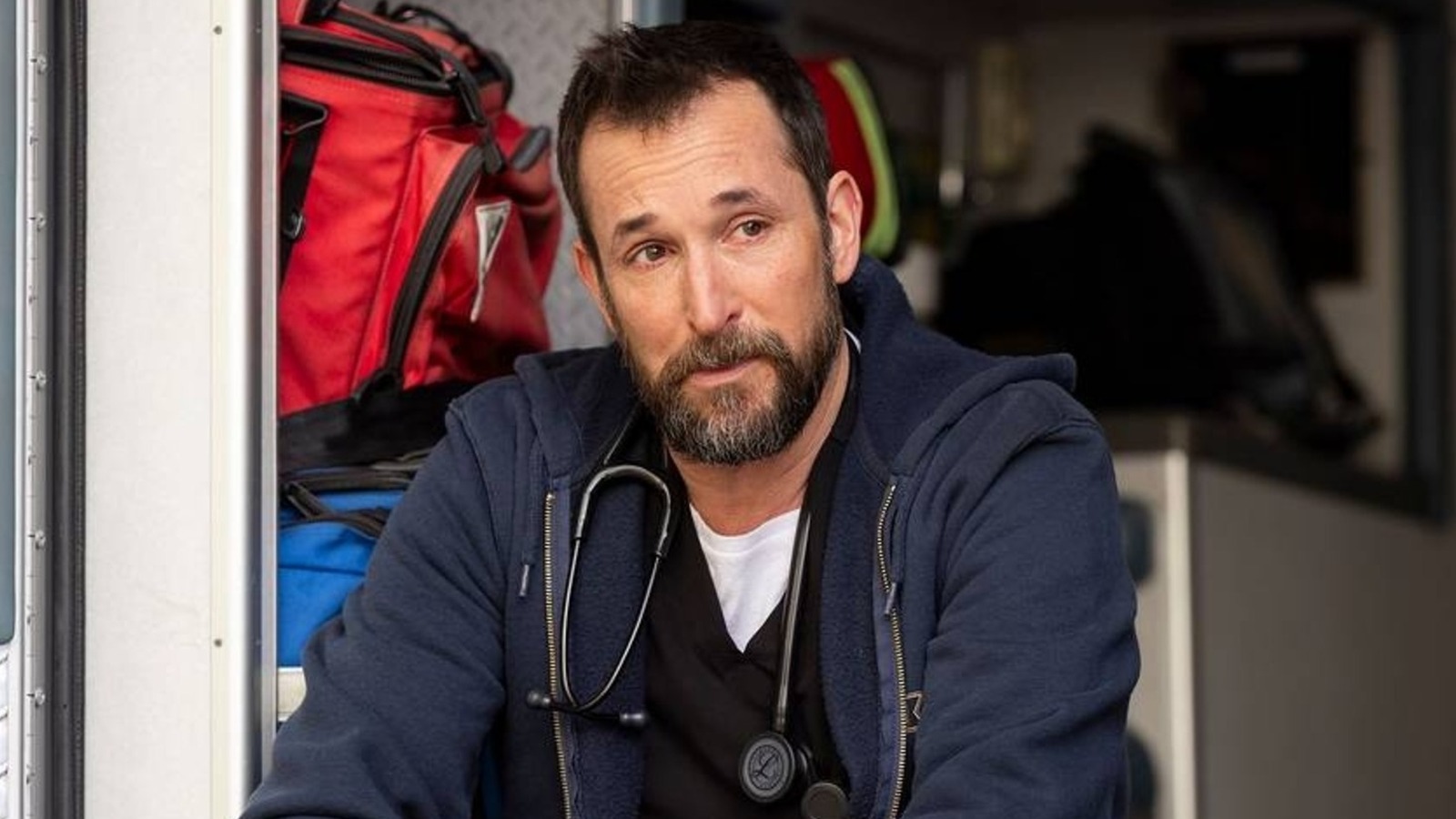

The actor talks about the deep bench of acclaimed filmmakers he's collaborated with, and working with Chicago actors for his own directorial debut.

Michael Shannon’s feature directorial debut, “Eric LaRue,” is of a piece with the anguished psychological dramas for which he’s acclaimed as an actor. But its painful subject matter also reflects the burning social conscience he says he’s long been driven to interrogate through art.

An adaptation of Brett Neveu’s 2002 play of the same name, this bleak drama (in limited theaters April 4, on digital April 11) confronts gun violence, crises of faith, and the inability of organized religion—with its helpless thoughts and prayers,its facile concepts of healing and atonement—to help those grappling with unimaginable tragedy and unanswerable questions.

Left devastated and set adrift after their teenage son murders three classmates in a school shooting, Janice (Judy Greer) and husband Ron (Alexander Skarsgård) struggle to navigate their grief and guilt, as well as the shell-shocked isolation they feel in a small town torn apart by the crime. Seeking guidance from rival religious congregations, one overseen by a Presbyterian pastor (Paul Sparks) and the other by a motivational preacher (Tracy Letts), the pair set about preparing to meet with the other mothers involved, even as Janice anticipates another difficult reunion: with her son, Eric (Nation Sage Henrikson), at a prison she has yet to visit.

Michael Shannon first encountered the play in 2002, at Chicago’s A Red Orchid, the Old Town theater company he helped to found more than three decades ago, and which he’s returned to across his career (including just last year, to star in Levi Holloway’s “Turret,” about a soldier in a bunker at the end of the world). Seeing “Eric LaRue” as an audience member, coming off his acclaimed lead performance in the same theater company’s production of “Bug,” Shannon was captivated by the play’s exploration of what he refers to as “the fundamental confusion that is woven into the fabric of our American life,” a confusion bred of not only the trauma and hardship that attends tragedy but our collective inability to care for one another through such ordeals.

Revisiting the material years later as a screenplay, Shannon found it every bit as troubling and thought-provoking as he had on the stage. Seized by the urge to direct a feature film adaptation, he met with producer Sarah Green, who’d worked with Jeff Nichols on all his films since “Take Shelter,” and secured her support; Nichols also came aboard as an executive producer. Though the pandemic delayed production for a few years, the project moved forward quickly once it was feasible to do so. Prep, filming, and post-production took place in just six months—despite the production relocating from Arkansas to North Carolina at the last moment after a state law banning nearly all abortions was triggered by the U.S. Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade.

In casting, Shannon called first on close friends and collaborators. Greer, he’d worked with on “Pottersville,” while he’s known Skarsgård since “The Little Drummer Girl,” and his friendships with Sparks and Letts date back decades. Other parts are played by A Red Orchid regulars; Mierka Girten and Larry Grimm portray Janice’s manager and boss, respectively. Jen Engstrom—who played another part in the 2002 production of “Eric LaRue”—plays one of the grieving mothers; Steppenwolf regular Kate Arrington, to whom Shannon is married, and Annie Parisse, who’s married to Sparks, play the other two.

Shannon bringing together this ensemble—plus skilled craftspeople like production designer Chad Keith (“Take Shelter”), cinematographer Andrew Wheeler (“God’s Country”), and Mike Selemon (“Daine”)—results in a sensitive drama that punches well above its weight class as a modest indie production, affording Greer a particularly moving showcase while granting the other actors the opportunity to similarly play against type. And as a director, Shannon displays a patient and steady hand, lingering in moments of mournful ambiguity and terrible silence.

At the Gene Siskel Film Center in Chicago, ahead of introducing a special screening of the film, Shannon—sporting an eccentrically half-shaved haircut in likely reference to R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe, whom he’s been channeling on stage as the lead singer for a cover band that just finished touring the country; more on that later—spoke to RogerEbert.com about his career-long interest in the fissures of American society, what keeps drawing him back to the proverbial bunker, and art as a chamber for shared experience.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Tell me about first encountering this play; you saw it staged after not only the Columbine school shooting but after 9/11. I know you weren’t involved with the play directly, though you’d just starred in “Bug” for A Red Orchid, the same theatre company, but I’m curious what it was like to see “Eric LaRue” staged at a time of such grief, anger, and confusion — then to revisit it years later, to discover it still so relevant.

First of all, what’s truly spooky about “Eric LaRue” is that Brett wrote it before Columbine, so he almost anticipated that in a strange way. Of course, it wasn’t too long after he wrote it that Columbine did happen, so it’s understandable that people make the correlation. When I saw it in 2002, it just broke my heart. Kate Buddeke, the actress who played Janice in that production, was also in “Bug,” and she’d played Agnes in “Bug,” so I obviously was very close with her, having done “Bug” with her for all that time.

To see her switch gears into playing Janice was mind-blowing, because they’re both two very intense roles, obviously, but very different; an actor named Will Clinger was playing Steve. And I was just so touched by Brett’s exploration of how people want to help one another, despite the fact that they don’t really know how to; they make the attempt nonetheless and in the process of doing that evolve, somehow, personally or together. I kept going to see the play. I saw it several times.

Years and years went by, and I directed Brett’s play, “Traitor,” which was a modern retelling of [Ibsen’s] “The Enemy of the People.” At closing night for “Traitor,” Brett gave me the screenplay of “Eric LaRue,” and I read it, and it was like getting hit by a bolt of lightning. It struck me to my core, and I thought when I read it, “This screenplay is about everything that’s important right now in our society. The true fissures, the cracks in the foundation of American civilization, are contained in this story.” I found that very inspiring, and it motivated me to do something that I otherwise probably would not be inclined to do, or at least that I had stated I had no interest in doing, which was directing a film.

In bringing “Eric LaRue” to the screen, and casting your own company of performers to inhabit it, I was pleased to see Tracy Letts as Bill Verne, one of the local preachers vying for the faith of these bereaved parents. At Steppenwolf and beyond, Letts is one of our great playwrights; in the early years of your career, he cast you in “Bug” and “Killer Joe,” two productions that explore that same sense of fissure, in human psychology and larger American society. What can you say about working with Tracy and how those roles informed others you’ve explored in your career?

Tracy was a no-brainer in that part. He just has such an authority about him, and he radiates wisdom. In this particular scenario, whether that’s genuine wisdom or not is to be debated, but he has an aura about him that he knows what’s up.

I can’t say this is always true 1,000% of the time, but, most of the time, when I’m finding things to work on, I really do have a focus towards what I think would be helpful for people to watch—or edifying or inspiring. I don’t just want to further my career, or be a movie star, or any of that, because I feel like the satisfaction of that is limited. It does have a certain charm, the first time you walk down the street and somebody says, “Oh, I saw you in a movie.” You kind of blush and say, “Oh, you know, now people know who I am.”

Well, that goes away. 10 years after the fact, you’re like, “Alright, fine, yes, I’m in movies. Great. But what now? What next?” And so, if you’ve got a platform, or an ability to influence people or make them think about things in a different way— especially things that they maybe don’t want to think about—but you can find a way to do it that’s entertaining and captivating, then that’s what makes sense to me to do.

In thinking about “Eric LaRue” as your feature directorial debut, I was struck to consider how many talented directors you’ve worked with, on stage and screen. One of the gifts you’ve been given as an actor has been that these directors afford you the time and the space to truly develop a character, to dig down and find that visceral emotion for which you’re known. You do the same for your actors in “Eric LaRue.” Who comes to mind, when you think about the directors who’ve afforded you that space, and what did you consciously carry from those experiences, if anything, into this film?

It’s crazy, because I have worked with quite a gallery of directors—no doubt about it. I feel very blessed to have done so. A lot of them have been very encouraging to me, and it’s hard to point a finger in any particular direction, to say, “This person is who I learned all the secrets of directing from.” It’s something that becomes almost embedded in your subconscious after decades of doing this work, both in film and in theater. And I’ve learned as much from directors that I’ve done storefront theater with as I have from internationally acclaimed filmmakers. You pick things up as you go.

Obviously, I have a very long-standing relationship with Jeff Nichols. I love working with Jeff. I’ve been in all his films. Jeff, by and large, has a tendency to let me run my own motor, you know? I guess there’s an understanding that we have, between one another, that I get what he’s selling. I don’t know. Getting people to act on film is a very delicate thing. I think you summed it up very acutely. You have to give people space. You can’t fill their head up with a bunch of junk. You don’t want to be filming somebody who’s sitting there thinking about what you just told them to do. You want people to not be thinking, basically; you want them to be being.

I think it’s important to understand that most actors show up to work filled with a lot of anxiety, and they’re scared. Even if they’re prepared, even if they put a lot of thought into what they’re going to do or attempt to do, they still show up needing someone to help them feel safe. That was something I was very focused on, on my set—not by coddling them, or filling them with false platitudes, or whatever, but just decompressing, because of the scope of the story we’re telling. It’s a story that feels really important, because it is important; what I wanted to do on my set was diffuse that, a little bit, to say, “It’s okay: you don’t have to tell the whole story in this scene. Just relax, and be curious about what’s happening.” And that yielded a lot of interesting results.

Judy Greer, as Janice, reflects at multiple points in the film on her anxiety about staying inside, about the need to leave her home and not become confined to it, though it’s a psychological confinement she’s enduring as well. You mentioned Jeff Nichols just now, and I recently revisited “Take Shelter” — the last time I was at the Gene Siskel, actually, as part of Filmspotting Fest — a film about a man, plagued by apocalyptic visions, building a storm shelter in response. This concept of bunkers, of the crucibles we find ourselves in, recurs throughout your career—in films like “Bug” and “The End,” in plays like “Turret” at A Red Orchid last year. What power does the bunker hold for you?

I think the reason I keep revisiting the bunker is because I find the world to be an incredibly horrifying, chaotic shitshow that I struggle to even deal with, at all—in any way, shape, or form. So, bunkers make a lot of sense to me. I frankly don’t know how anybody is keeping their wits about them nowadays. But also, beyond societal or anthropological concerns, on a personal and emotional level, so many people are very careful about how much of themselves they are willing to share with one another.

That’s another thing that I found very moving about this story. It’s a story about a woman who’s saying, “I do want to share. I want to share, but who will share with me? Who is open?” She keeps reaching out to people that ultimately are not available or willing to participate in the relationship. And I found that very moving, as a theme in the movie.

Bunkers are a very real thing, you know? Three are people building bunkers all over the freaking world. I mean, the whole impetus for “The End” was Joshua Oppenheimer meeting a wealthy fellow over in Malaysia, who said, “Hey, do you want to see this? I’m building a bunker for my family, in case everything goes south.” He got a tour of this bunker, and that flourished in Joshua’s imagination into “The End.” A lot of these rich people are aboard the bunker train, as it were.

Related to that, one throughline in your filmography is this sense of impending doom, and the portrayal of that anxiety people feel as a result. I’ve rarely, if ever, seen a more realistic depiction of contemporary anxiety than in “Take Shelter,” and given the issues of mental health and trauma in “Eric LaRue,” I’m curious to what degree you see these types of portraits of mental health as being continually relevant and important for you to explore in your work.

Oh, they feel super relevant to me. I mean, I can think of very few people that I know in my life who don’t struggle with some form of—I think mental illness is probably an extreme term, but certainly anxiety and depression. It’s an epidemic. It’s everywhere. And it’s not just biochemical; it’s beyond that. It really is connected to the world that we live in.

And if you look at what’s happening right now in our country, just when you think that the people in charge couldn’t care less about you, they shockingly find a lower level to sink to, in terms of their lack of compassion or empathy for people. And it’s so ironic, because they’re in power because people that felt powerless and disenfranchised voted for them. It’s like having cancer and saying, “Well, can somebody inject me with more cancer?” You know, it makes no sense.

Art can’t solve problems, I don’t think. It’s not a problem-solving entity. It’s not medicine, it’s not a solution, but it’s a chamber in which these shared experiences can reverberate and echo and make people feel like they’re a part of something, that they’re not alone. It can help them digest and ruminate about what they’re experiencing in their own lives.

That’s beautifully put, and it leads me to ask about those other forms of art as shared experience that you’ve been passionate about recently, like music. Your love of jazz is widely known, and you just finished a national tour, celebrating the 40th anniversary of R.E.M.’s “Fables of the Reconstruction” by performing it live with guitarist Jason Narducy and a backing band. What does playing music do for you?

Yeah, I just finished the tour. We did 20 shows in a month. Holy moly. We just finished last night. And what a blessing. What a beautiful thing. This is the flip-side of what I’ve been talking about, because I feel like—and this is a lot; perhaps it sounds grandiose to attach this to what basically was a cover band going around playing R.E.M. songs—but we somehow managed, as a group, the six of us in the band, to bring people a lot of joy. At least, that’s what we’ve heard on the road.

To be able to go all over the country… We started on the West Coast, then played the Midwest, the East Coast, and every stop along the way, in the midst of this very unsettling time that we’re in right now. Giving people a respite from that, just allowing them to abandon themselves to this music that they love, with the knowledge that it’s extremely, highly unlikely they’re ever going to see the actual band do that again, I’ve felt very fortunate to have the opportunity to give that to people.

We’re almost out of time. When you think about what’s next, are you more excited about the prospect of continuing to act, directing again, potentially carrying on with R.E.M. by touring “Lifes Rich Pageant” next, or something else?

I’m excited about all of it! I mean, I’m doing a play in London this summer. I haven’t done a play in London in years, and I’m super excited about that. It’s a play called “A Moon for the Misbegotten,” by Eugene O’Neill, opposite Ruth Wilson, with a wonderful director named Rebecca Frecknall, and I’m looking forward to that.

I think I’ll be working with Jeff Nichols in the fall, which I’m really looking forward to. There’s another script that I’m circling around directing, written by another playwright I know named Brett—Brett C. Leonard. It’s called “The Long Red Road.” That’s in very early stages, though.

And then, I think we’ll do “Lifes Rich Pageant.” I mean, it’s a-ways out, and there are always logistics to figure out, because all the musicians in this band are world-class musicians, and everybody wants them. We’ll see if we can get everybody in the same place at the same time, but they’ve all expressed interest in doing it. Maybe next year, we’ll find that time.

We’re doing “Fables,” actually, with a little U.K. tour in August. We’ll play six dates in the U.K., and then the last show, actually, we’re going to play in Dublin, because the Irish really love R.E.M. That show’s actually selling so well that they’ve moved it to a bigger venue.

Oh, wow.

[laughs] Yeah. It’s crazy.

“Eric LaRue” opens in theaters April 4, and on digital April 11, via Magnolia Pictures.

![American Airlines Passenger Spotted Texting Women Saved as ‘Lovely Butt’ And Another, ‘Nice Rack’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/american-airlines-passenger-texting.jpg?#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-–-Overview-trailer-00-00-10.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)