Inside Tskaltubo, Georgia: the Abandoned ‘wellness Resort’ About to Change Forever

At one time, it was one of the chicest towns in the Communist Bloc.

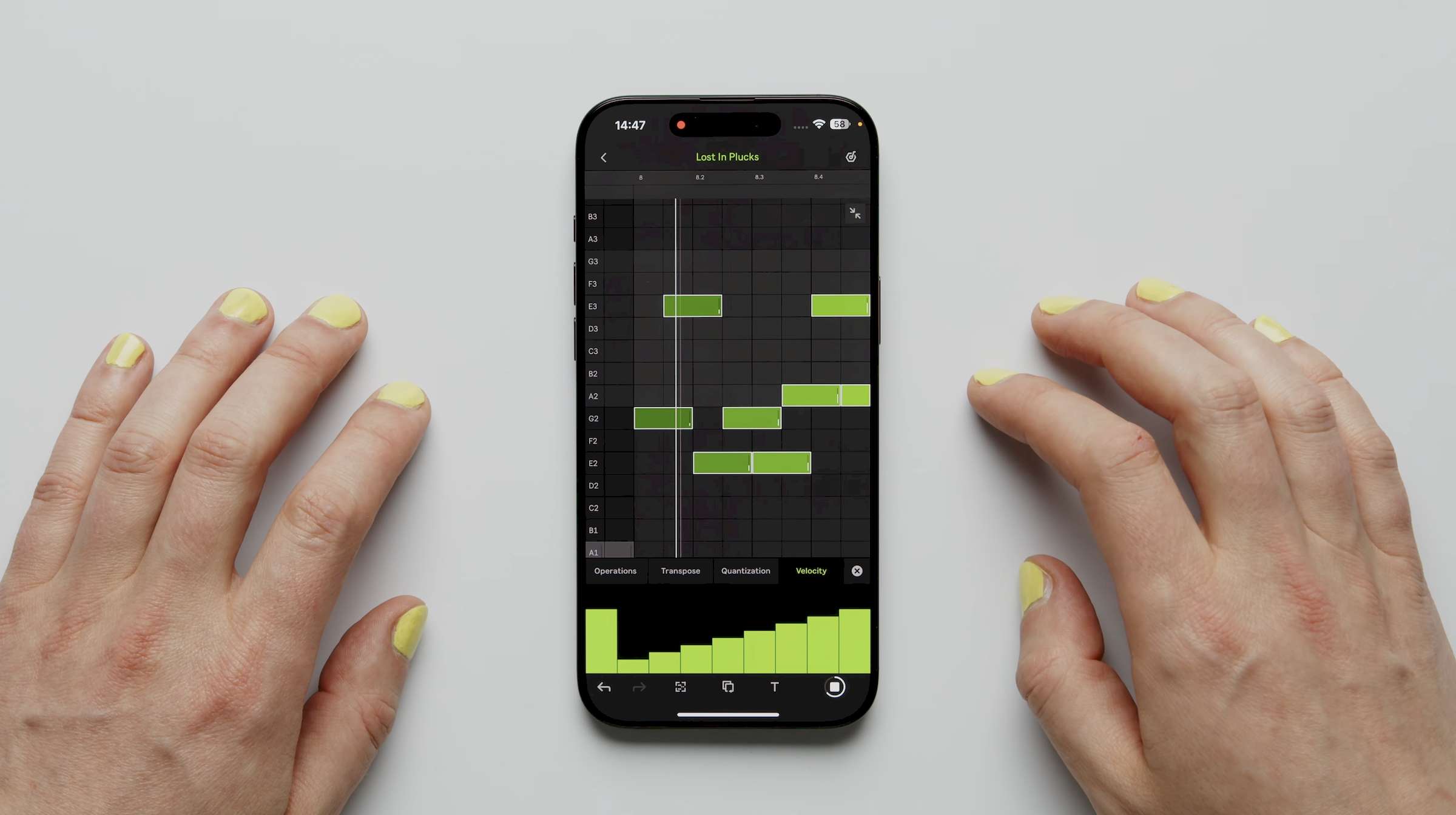

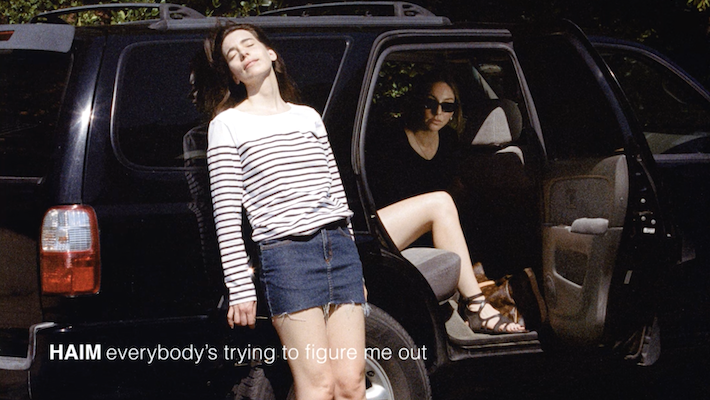

As we approached the grand facade of the abandoned sanatorium, we could hear music echoing through the building and see a clean-up crew sweeping confetti and stacking chairs in the columned entrance hall. Further in, the star of the day — a bride with waist-length brown curls — posed in her wedding dress at the top of a stone staircase. Her train cascaded down the steps, turning shades of gold by the brightly setting sun. Occasionally, the groom was even invited into the pictures.

It was the scene at Hotel Medea, also called “Sanatorium Medea,” in Tskaltubo, in the country of Georgia. Though it was officially abandoned for decades, it never stopped buzzing with life. Locals and tourists alike used it as a hangout, an Instagram backdrop, and, yes, even a wedding venue.

Photo: Mikhail Starodubov/Shutterstock

It seemed romantic, and my partner and I walked through the vast columned hallways, up crumbling staircases, and onto a rooftop terrace. From this high vantage point, we could take in the full scale of the building. The structure formed a massive rectangle around a courtyard, with four wings stretching to the sides. In the courtyard below, a once-grand swimming pool sat overgrown with bushes.

Just one abandoned building of this scale would thrill any urban explorer, or “urbexer” — people who enjoy exploring abandoned and off-limits places. There are more than two dozen such buildings scattered through Tskaltubo, a small town in Georgia, a country sandwiched between Russia and Türkiye. I’d spent five days exploring Tskaltubo, but still hadn’t seen it all.

It’s a special place where still-abandoned buildings have been reclaimed as community spaces, though they may not function as that for much longer. Renovation projects are underway, and soon, many of the atmospheric ruins will be transformed — or lost — forever.

A brief history of Tskaltubo

Photo: Shutterstock/BGStock72

Tskaltubo sits atop bubbling hot springs once famed across the Soviet Union. A direct train from Moscow brought visitors to bathe in radon-rich thermal waters, believed to relieve rheumatism and inflammation. Most resorts opened in the 1920s.

In 1931, the Georgian Soviet Republic designated it as an official “balneotherapy center,” and the town quickly transformed into one of the most prestigious health resorts in the Communist Bloc. More than 20 wellness resorts called sanatoriums were built to combat chronic illnesses like psoriasis and arthritis, complete with spas, theaters, libraries, and conference halls. By the 1950s, Tskaltubo was drawing up to 125,000 visitors annually. Joseph Stalin allegedly visited in 1951 to treat an ongoing case of rheumatoid arthritis in his leg, though records on his visits are sparse.

Photo: Fotokon/Shutterstock

Tskaltubo wasn’t just for the elite, though. Some resorts were named after the workers they served, such as Sanatorium Metallurgist, named for the steelworkers and miners it catered to, known as metallurgists. Under the Soviet constitution, laborers had a right to “rest and leisure.” It allowed doctors to issue all-expenses-paid vouchers for two-week stays in Tskaltubo, where patients received treatments ranging from hot spring baths to electrotherapy.

Then, in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. The resorts shut down, tourism disappeared, and Tskaltubo became a quiet farming town, its once-grand buildings left to decay. It’s been described as a ghost town during those years, but the term doesn’t quite fit, as Tskaltubo’s sanatoriums have never been entirely empty.

After the 1992 Abkhazia conflict in the country displaced more than 200,000 Georgians, around 10,000 refugees found shelter in the abandoned buildings. It was supposed to be a temporary housing solution, but many families ended up living there for decades. People died and were born in the former sanatoriums. It’s only in the past couple of years that most of those Abkhazian refugees have been rehoused in formal apartment blocks.

Photo: Eloise Stark

Locals claimed the emptied resorts in other ways, too. During the 2020 parliamentary elections, some buildings were used as polling stations; you can still see the Covid-era stickers to ensure social distancing between voters. There are unofficial gatherings, too. In daytime, you’ll see couples seeking out secluded corners, and groups of teenagers hanging out, chatting and taking photos. Empty beer bottles and murals of varying artistic quality mark the late-night festivities that have taken place within these walls.

In recent years, Tskaltubo has also attracted international visitors, as tourism to the country of Georgia has grown. According to the National Statistics Office of Georgia, there were 7.4 million international visitors in 2024, up 4.2 percent compared to the previous year and 32 percent compared to a decade earlier. Now, the town has become well-known as one of the world’s top urbex destinations. Travelers have become a regular sight in the abandoned sanatoriums, alongside people from the surrounding town and those families who have made the buildings their home.

What’s next for Tskaltubo?

Photo: Lucas M. Kaiser/Shutterstock

With tourism growing in Georgia, Tskaltubo is changing. The government’s “New Life for Tskaltubo” plan, launched in 2022, is designed to transform it into a “modern, world-class” spa town. Investors from Georgia, Egypt, Qatar, and beyond have purchased several of the former resorts, closing them off to visitors. Modern renovations are underway on a handful of them.

The plan’s vision is clear: a luxury wellness destination catering to affluent travelers. Opponents of the plan are concerned that the high prices the resorts will likely charge will make the resorts financially inaccessible to locals. A night at Tskaltubo Legends Resort, a spa that reopened in 2011, costs $80 — a steep price in a country where the average monthly salary is under $800.

But something more than just affordability is at stake. Privatizing these buildings will put an end to Tskaltubo’s unique community spaces, which act as a strange “third space” by being neither operational, nor entirely abandoned. What follows may be luxurious, but might never hold the same magic as these palatial buildings that belong to everyone and no one at the same time.

What to see in Tskaltubo before it changes

Photo: Eloise Stark

Tskaltubo is arranged around a central park that’s home to several bathhouses and a natural spring fountain where visitors can put their hands under the roughly 93-degree F, mineral-rich water. The resorts are scattered throughout town and are close enough to one another to easily explore on foot. There are several dozen abandoned buildings, but some are more interesting than others.

Visiting Tskaltubo’s empty sanatoriums is generally legal, as many are situated on publicly accessible land. However, properties acquired by private investors are often secured with fences and may have restricted access.

Soak in Spring 6

The largest building in Tskaltubo’s central park is Spring 6 (formerly Bathhouse No. 6), one of the rare Soviet-era spas that never closed in Tskaltubo. It’s a great place to go for a soak after the dusty business of exploring the empty buildings. Visitors can book a variety of traditional and more unexpected wellness treatments, from sports massages to speleotherapy (breathing inside a cave) to electroshock therapy. Treatments are available to book online or in person.

Bathhouse No. 8

Bathhouse 8 in Tskaltubo, Georgia. Photo: Eloise Stark

A masterpiece of brutalist architecture, this former public spa resembles a concrete UFO that landed in the middle of the park. Inside, under a rounded roof, individual baths are arranged like petals around central fountains. On the algae-covered walls, you can still make out nature scenes, including dancing deer. Sunlight streams through a circular hole in the roof, casting dramatic shadows. Today, it’s a popular hangout, and the walls are covered in street art.

Sanatorium Metallurgist

Once reserved for steelworkers and miners, Sanatorium Metallurgist is one of the best-preserved sites in Tskaltubo, with ornate original features throughout. The wow factor begins in the main entrance hall, where a massive chandelier hangs from a ceiling adorned with intricate moldings.

Visitors can explore an old library, doctors’ offices, and even a theater, where a crumbling grand piano still stands. On the second floor, keep an eye out for the pink and blue elevators — one for ladies, the other for gents. Around the back of the building is a stunning glass atrium, where a single tree grows from a crack in the concrete floor.

Sanatorium Medea at the Medea Hotel

Medea Sanitorium in Tskaltubo, Georgia. Photo: Eloise Stark

One of the most photographed sanatoriums, Medea’s grand facade of columns and arches makes it a favorite for weddings. Inside, visitors can climb sweeping staircases to reach the roof terrace which overlooks the courtyard. The inner hallways are also interesting, inhabited until recently by Abkhazian refugees. Today, you can find reminders of their presence, including posters on the walls, discarded clothes and toys, and even family photos.

Children’s Playground at Sanatorium Gelati

Mosaics were widely used in Soviet-era art and architecture, and this children’s playground is one of the finest examples left in Georgia. Stark geometric patterns form a climbing frame, adorned with colorful tiles that depict human figures, plants, and animals, including giraffes and bison.

Sanatorium Imereti

Photo: Fotokon/Shutterstock

A stray dog appointed himself as my guide when I visited Sanatorium Imereti. Much of the building is inaccessible, but what remains is breathtaking. It led me first through a field of wildflowers, where I stumbled across a rotunda with arched doorways. Inside, blue paint peeled from the walls, revealing intricate moldings still remarkably intact.

From the rotunda, I followed my four-legged companion into the main building, through columned hallways, up grand staircases, and into an abandoned theater. But at one point on an upper floor, where gaping holes in the floorboards revealed the rooms below, he refused to go any further. If you decide to explore this beautiful spot, proceed with extreme caution.

How to visit Tskaltubo

Tskaltubo is 14 miles from Kutaisi International Airport, which connects to major cities in Europe and the Middle East. Car rentals and taxis are readily available at the airport for a quick transfer to town.

Alternatively, you can visit Tskaltubo on a day trip on an organized tour from Kutaisi or even Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital (about a 3.5-hour drive away). Companies like Budget Georgia or Friendly Tours offer one- and two-day options.

Tskaltubo is a small town of around 7,000 people and has most of the facilities you would need for a short stay. There are hotels, restaurants, cafes, supermarkets, and ATMs that accept international cards. However, some restaurants only take cash, so it’s best to come prepared.

When visiting, be mindful of residents. Some of the abandoned sanatoria are still inhabited. Always respect people’s personal space and avoid entering private apartments. Never take photos of homes without permission. Most residents are accustomed to visitors exploring the sanatoriums, but a little consideration goes a long way in maintaining good relationships.

Urban exploration tips

Photo: BGStock72/Shutterstock

The golden rule of urban exploration is to leave everything how you found it. Don’t take any of the objects you find as souvenirs, don’t force entry into locked buildings, and don’t damage anything. And, of course, prioritize safety. If a structure looks unstable, don’t take the risk.

The safest way to explore the abandoned buildings is to hire a guide for the day. You’ll not only benefit from knowing what areas are safe to explore, but also get insight into their local knowledge of the town’s history and current events. ![]()

![Free Beta Weekend Available Now for ‘Stygian: Outer Gods’; New Gameplay Trailer Released [Watch]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/stygian.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![Extended Superman Clip Shown To Audiences At CinemaCon [UPDATE: Now Here]](https://lrmonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Superman-Trailer-2-1024x832.png)

![‘Fantastic Four: The First Steps,’ ‘Thunderbolts,’ ‘Tron: Aries,’ Top Walt Disney Studios Previews [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/03215859/FantasticFourSS.jpg)

![Naming Your Baby? That Choice Could Haunt Them On Every Airline Upgrade List [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/upgrade-list.webp?#)