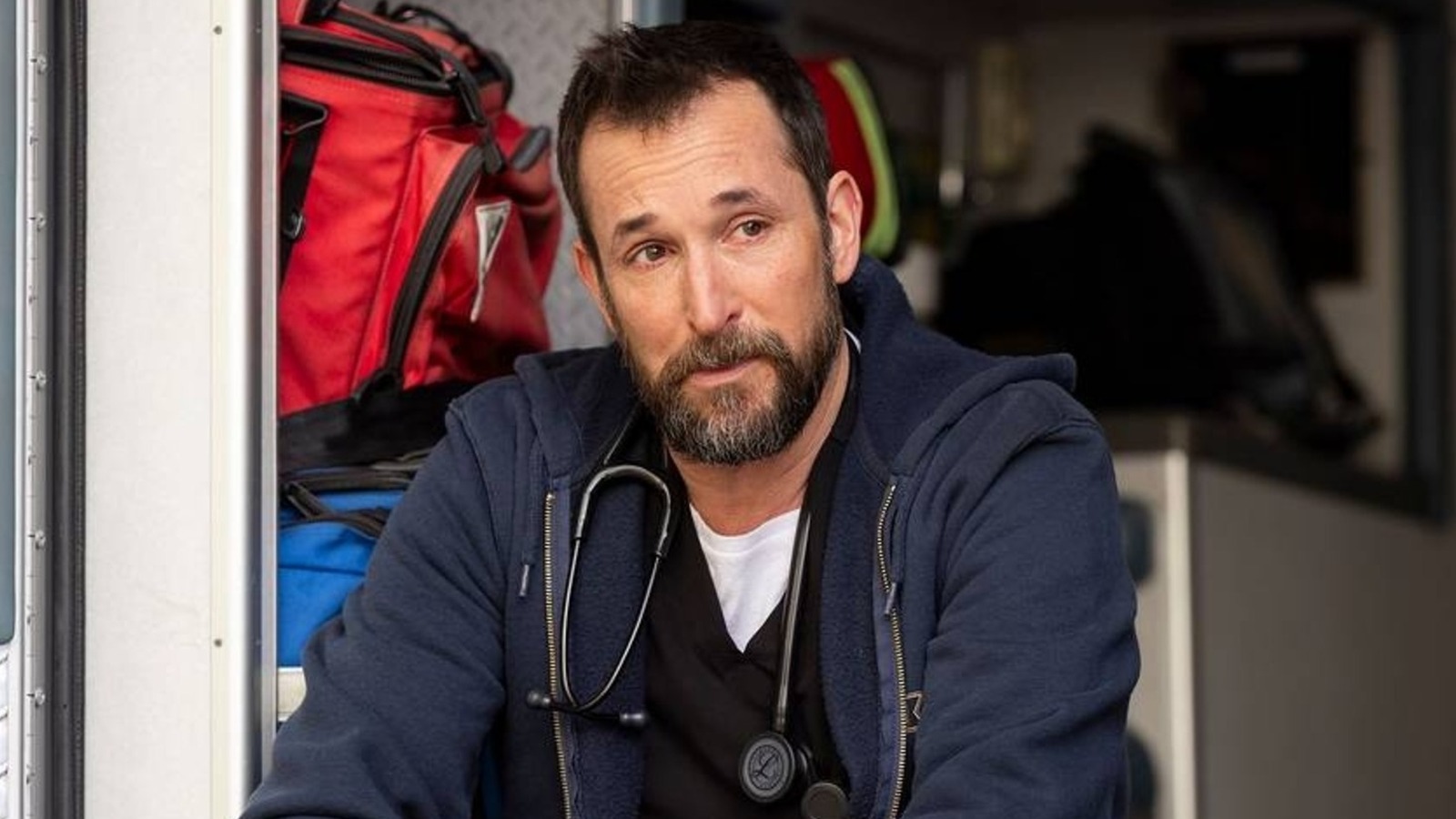

‘El Mural de la Conquista’ (‘Mural of the Conquest’) in San Bartolo Coyotepec, Mexico

Oaxaca stands out for its diverse gastronomy and culture, with one of the country’s highest percentages and diversity of Indigenous populations. These cultures are showcased in varied artesanías (handcrafts) or artes populares (popular arts). In Oaxaca, like in other states, each town specializes in a specific craft, and in the case of San Bartolo Coyotepec, its craft is pottery made from a distinctive local black clay (barro negro). Tzompantlis, skull racks from Mexico’s pre-Columbian period, were common across several peoples, including the Maya and the Zapotec. Perhaps the best example is the one in Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City). With their striking display of neatly organized human skulls, tzompantli have inspired many modern artistic interpretations, including “El Mural de la Conquista” (“The Mural of the Conquest”). Artist Carlomagno Pedro Martínez created this work, which was first displayed in Paris at the La Villet Cultural Center in 2002. The mural features a central tzompantli panel and makes symbolic use of other skulls, including a much smaller tzompantli, on the floor section. In front, subtitled “Apology of the Conquest,” five old women represent five centuries since the Spanish conquest, as well as a funeral. The back shows a map of Mexico and two armed figures—one resembling a revolutionary from the early 1900s, possibly Emiliano Zapata, and another wearing a balaclava typical of the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation). Carlomagno’s Zapotec ancestry connects both revolutionary movements to contemporary Indigenous resistance. The lower panel features skeletons with insect features above a skeleton representing Martín Cortés, son of conquistador Hernán Cortés and his Indigenous interpreter Malintzin (also known as Malinche), often considered one of the first mestizo Mexicans. This mix of peoples and cultures appears elsewhere on the mural, like the upper panel where skeletons appear atop a Christian church and a pre-Columbian pyramid. The side panels depict violent cultural clashes that ultimately forged a new Mexican culture. Martínez is also the director of the State of Oaxaca Museum of Popular Art (MEAPO), which he helped establish through fundraising beginning in 1994. After opening in 1996, the museum reopened in its current location in 2004, showcasing not only San Bartolo Coyotepec’s distinctive barro negro, but also works from across Oaxaca. The museum’s upper floor houses a mask collection, many from coastal regions and featuring real animal elements like hair and horns. The museum also has an active calendar of temporary exhibits, showcasing up-and-coming artisans as well as established masters of their craft.

Oaxaca stands out for its diverse gastronomy and culture, with one of the country’s highest percentages and diversity of Indigenous populations. These cultures are showcased in varied artesanías (handcrafts) or artes populares (popular arts). In Oaxaca, like in other states, each town specializes in a specific craft, and in the case of San Bartolo Coyotepec, its craft is pottery made from a distinctive local black clay (barro negro).

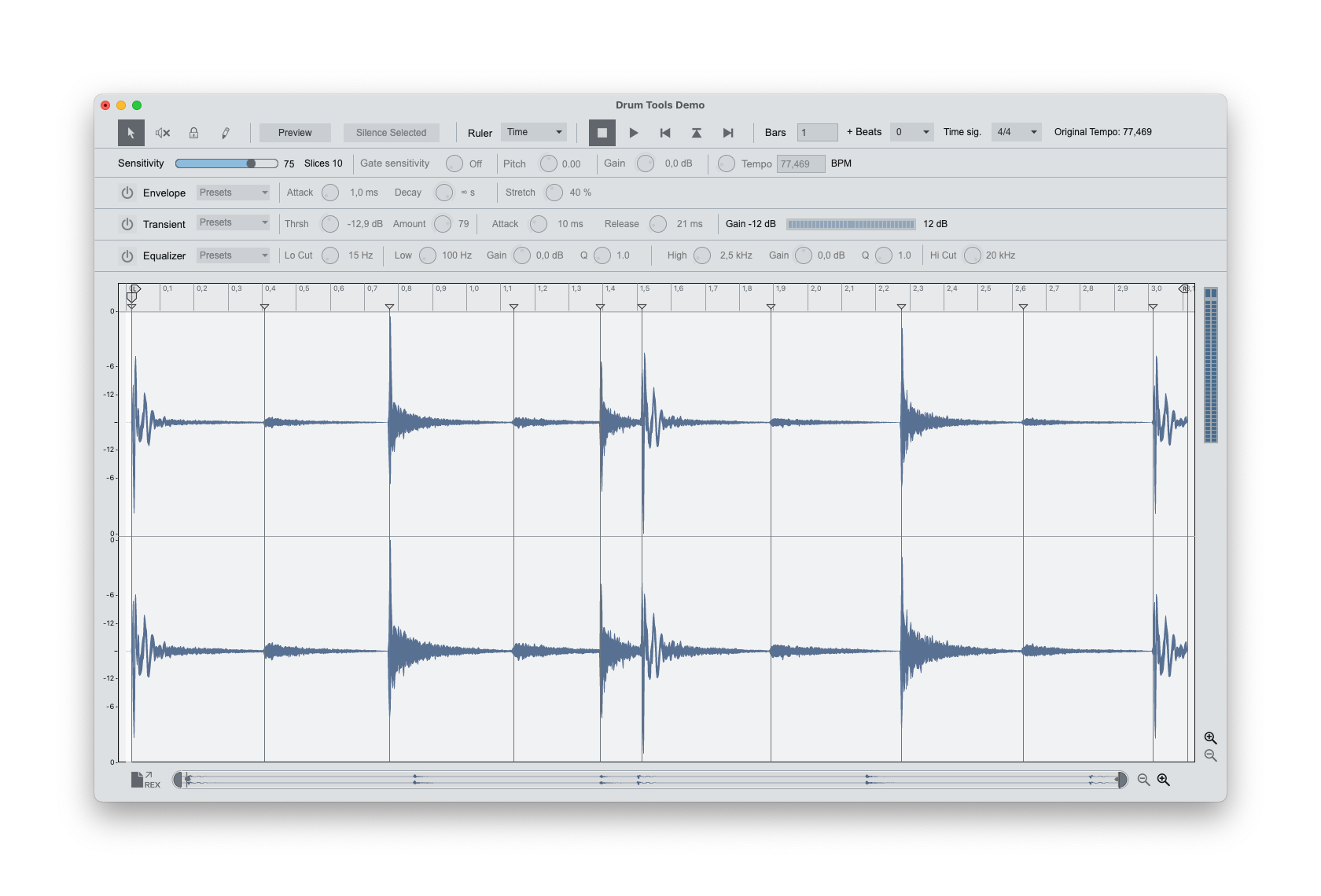

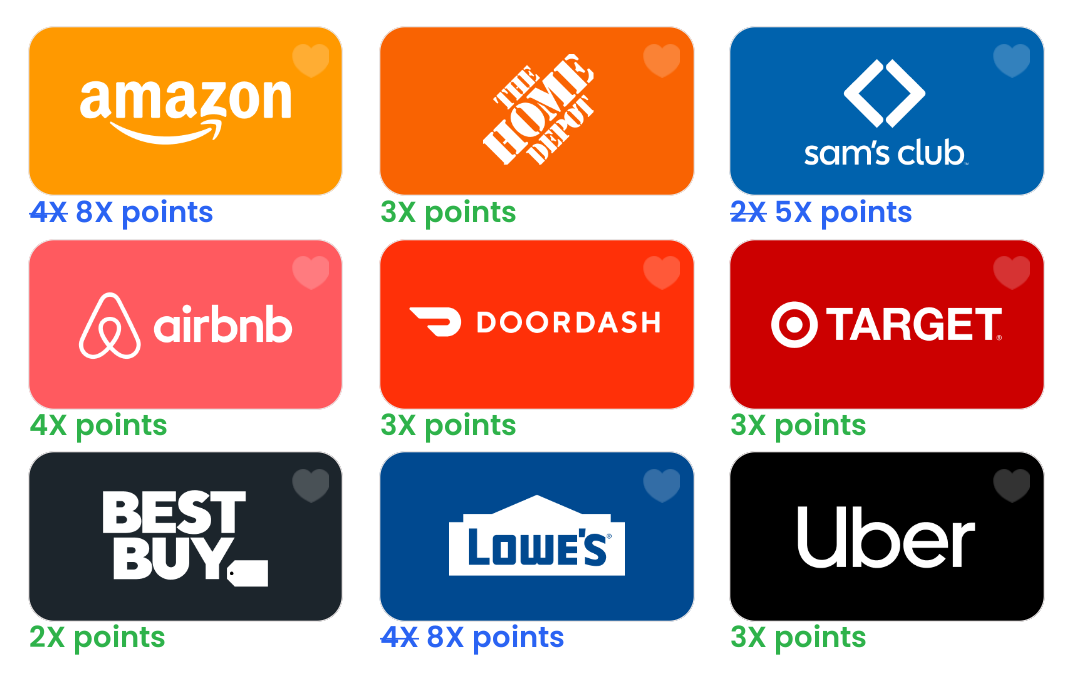

Tzompantlis, skull racks from Mexico’s pre-Columbian period, were common across several peoples, including the Maya and the Zapotec. Perhaps the best example is the one in Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City). With their striking display of neatly organized human skulls, tzompantli have inspired many modern artistic interpretations, including “El Mural de la Conquista” (“The Mural of the Conquest”).

Artist Carlomagno Pedro Martínez created this work, which was first displayed in Paris at the La Villet Cultural Center in 2002. The mural features a central tzompantli panel and makes symbolic use of other skulls, including a much smaller tzompantli, on the floor section. In front, subtitled “Apology of the Conquest,” five old women represent five centuries since the Spanish conquest, as well as a funeral. The back shows a map of Mexico and two armed figures—one resembling a revolutionary from the early 1900s, possibly Emiliano Zapata, and another wearing a balaclava typical of the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation). Carlomagno’s Zapotec ancestry connects both revolutionary movements to contemporary Indigenous resistance.

The lower panel features skeletons with insect features above a skeleton representing Martín Cortés, son of conquistador Hernán Cortés and his Indigenous interpreter Malintzin (also known as Malinche), often considered one of the first mestizo Mexicans. This mix of peoples and cultures appears elsewhere on the mural, like the upper panel where skeletons appear atop a Christian church and a pre-Columbian pyramid. The side panels depict violent cultural clashes that ultimately forged a new Mexican culture.

Martínez is also the director of the State of Oaxaca Museum of Popular Art (MEAPO), which he helped establish through fundraising beginning in 1994. After opening in 1996, the museum reopened in its current location in 2004, showcasing not only San Bartolo Coyotepec’s distinctive barro negro, but also works from across Oaxaca. The museum’s upper floor houses a mask collection, many from coastal regions and featuring real animal elements like hair and horns. The museum also has an active calendar of temporary exhibits, showcasing up-and-coming artisans as well as established masters of their craft.

![American Airlines Passenger Spotted Texting Women Saved as ‘Lovely Butt’ And Another, ‘Nice Rack’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/american-airlines-passenger-texting.jpg?#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-–-Overview-trailer-00-00-10.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)