World’s Weirdest Flying Car Uses Spinning Drums Instead Of Propellers For Better Stability

World’s Weirdest Flying Car Uses Spinning Drums Instead Of Propellers For Better StabilityYou’d be forgiven for mistaking it for a prop straight out of Blade Runner 2049—a cross between a drone and a dieselpunk art installation. But...

You’d be forgiven for mistaking it for a prop straight out of Blade Runner 2049—a cross between a drone and a dieselpunk art installation. But the Cyclotech Blackbird is very real, very airborne, and potentially the boldest reimagining of vertical flight we’ve seen in years. Forget spinning rotors and tilt wings. This machine flies on six mechanical barrels that look more at home in a gearbox than the sky.

The Blackbird isn’t a full-sized eVTOL yet—it’s a 750-pound demonstrator with zero seating and all the raw, experimental energy of a garage-built prototype—but it’s making history as the first aircraft ever to fly using six Cyclorotors. If that sounds like a new indie rock band, let’s get technical: Cyclorotors are essentially horizontal barrels with a rim of paddle-like blades, each capable of tilting mid-spin. Think Voith-Schneider Propeller meets Da Vinci sketchbook.

Designer: CycloTech

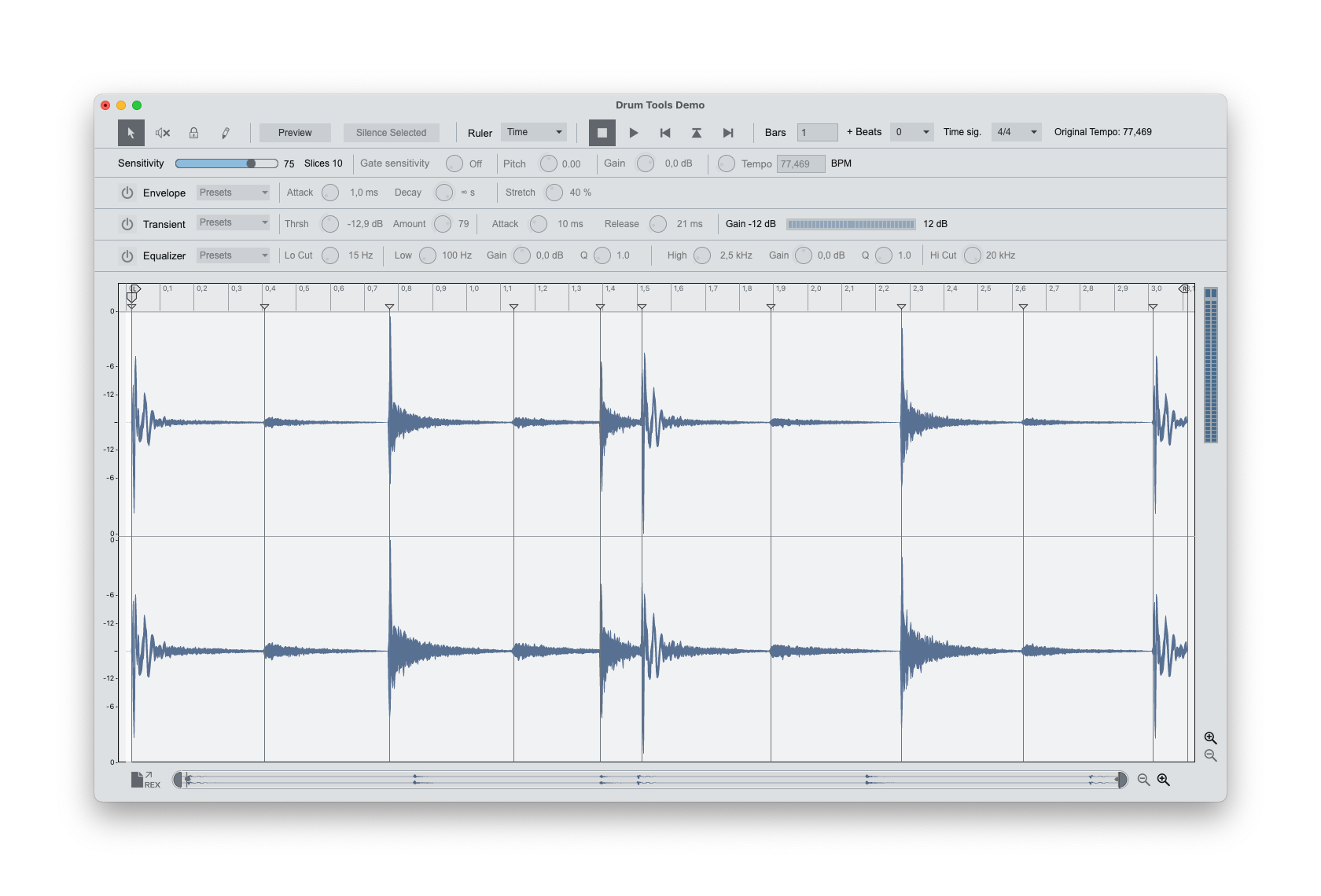

Just looking at it, it feels counterintuitive. Helicopters adjust pitch on long, spindly blades rotating around a central mast. Cyclotech’s system instead manipulates the tilt of short airfoils housed inside rotating drums – I’m in half minds to throw my clothes in and expect them to dry. The whole mechanism is a throwback to the swashplate designs of classic rotorcraft, but here, the blade adjustments are so rapid and precise they can redirect thrust 360 degrees on the fly—literally. Unlike conventional props that need to spool up or down to modulate thrust, Cyclorotors shift airflow direction on demand by altering blade orientation. That’s not a marginal upgrade—it’s a different language of control.

What does that mean in the sky? Micro-adjustments to keep hover stable in gusty wind. Immediate lateral thrust without banking. Redundancy across multiple axis-aligned rotors. And a footprint compact enough to not look totally dystopian on a rooftop pad. The current prototype has four Cyclorotors at each corner and two more mounted horizontally under the nose and tail. This six-pack layout allows the aircraft to twist, slide, or climb without angling its body—ideal for surgical maneuvers in crowded airspace.

But let’s not gloss over the awkward bits. Cyclotech’s voodoo barrels are mechanically complex, with a moving-part count that might make aerospace engineers sweat. And the blades, while arguably less intimidating than traditional rotors, still look like they could julienne a bird mid-flight. There’s also the looming reality that this thing won’t hit consumer or commercial markets before 2035—an eternity in eVTOL years.

Yet Cyclotech isn’t sprinting to market with air taxi dreams and urban mobility decks. The real play here is propulsion tech. Their goal isn’t to win the flying car race—it’s to build an engine platform that can be licensed across platforms, from drones to emergency VTOLs to cargo craft. It’s a modular, mechanical idea in an age of batteries and software.

Speaking of specs, the envisioned production model—tentatively called CruiseUp—is aimed at personal ownership. A two-seater with a top speed of 93 mph (150 km/h) and a max range of 62 miles (100 km) sounds humble, but keep in mind this isn’t an airliner. It’s a city-hopper, a flying commuter capsule for the well-heeled futurist. Range anxiety? Sure. But it’s enough for suburb-to-downtown hops, especially in traffic-choked megacities.

And if you’re wondering about the ride experience, Cyclorotors could deliver surprisingly smooth motion. Unlike quadcopters that jostle with every micro-correction, Blackbird’s 360-degree thrust vectoring promises a more composed hover and agile, side-slip maneuvers that resemble underwater thruster dynamics more than airborne flight.

There’s a whiff of nostalgia baked into the entire endeavor. It recalls an era when flight felt experimental again—when engineers were allowed to be weird and curious, and prototypes weren’t just sleek renderings but awkward, brilliant machines with exposed parts and ambitious dreams. The Blackbird is very much that. Aesthetically odd. Mechanically dense. Technically ambitious. And more than anything, a signal that aviation’s next leap might not be software-defined or purely electric—but mechanically radical.

It’s early days still, with test flights likely consisting of cautious hops and brief hovers. But the concept is up, airborne, and pivoting in the air like a sci-fi dragonfly. Cyclotech’s approach won’t dethrone the tiltrotors or ducted fans of the world anytime soon. But it might make them rethink what agility, control, and mechanical elegance really look like in the sky.

The post World’s Weirdest Flying Car Uses Spinning Drums Instead Of Propellers For Better Stability first appeared on Yanko Design.

![American Airlines Passenger Spotted Texting Women Saved as ‘Lovely Butt’ And Another, ‘Nice Rack’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/american-airlines-passenger-texting.jpg?#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-–-Overview-trailer-00-00-10.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)