An Untold Look at the “Debacle” of FCP7 to X

Eddie is the AI assistant video editor for pros and this week they just launched a trifecta of announcements to bring “ChatGPT” capabilities to Premiere Pro, DaVinci Resolve, and Apple’s Final Cut Pro with their powerful prompt-based AI video editing integrations, which we covered here.Eddie (the company, not the AI) has also started creating great editorial celebrating the movers and shakers that pushed forward our beloved production industry. See their previous epic narrative about the sunglasses billionaire who founded the RED digital cinema camera here.This month’s longform article takes a new look at the bombshell that is Final Cut Pro’s migration of 7 to X.An Untold Look at the “Debacle” of FCP7 to XApril 2011. Las Vegas. A stage. A reveal. A gasp. And then… the fallout.The launch of Final Cut Pro X didn’t just divide the editing world. It shattered it. Editors fled. Forums exploded. Legacy users cried betrayal. Apple, once the scrappy disruptor-turned-Hollywood darling, suddenly looked like it had fumbled the final reel.That’s the story. Or was it?What if the launch of FCPX wasn’t a mistake, but the moment? The moment that, fifteen years later, quietly reshaped how content is created today.This is the story with new eyes, clarified with the passage of time.Act I: Ahead of the TimelineBefore Final Cut Pro X, editing was frozen in time.Things were already digital. But the interface was analog at heart. Tracks. Bins. Timelines that looked like tape. Even Apple’s own Final Cut Pro 7 still clung to analog metaphors.Enter Steve Bayes, Apple’s Senior Product Manager for Final Cut Pro, and before that, Avid’s first ever instructor. The guy who literally wrote The Avid Handbook. The guy who trained an entire generation of editors on non-linear editors. He’d seen the old guard, helped build the tools they loved, but knew something needed to change.“We didn’t want editing to be about operating equipment,” Bayes later said. “We wanted it to be about storytelling.”But the deeper insight was this: the editor of tomorrow was not sitting in a post house. They were on a laptop, in a bedroom, in a park, with a DSLR and a YouTube login. Apple didn’t want this user just to be an afterthought, they were the thought.Act II: The BetApple debated everything. Scrap the timeline? Rethink audio sync? What would an editor’s canvas look like if they weren’t shackled by filmstrips?Before Final Cut Pro X, editing was like threading tape. Tracks for video. Tracks for audio. Everything had a lane, and moving one clip meant manually pushing or breaking everything else around it.If you’ve ever knocked your audio out of sync because you slipped one frame too far, you know what I’m talking about.From those early Apple debates came the Magnetic Timeline.A new way of editing where clips snapped into place, audio stayed in sync, and the visual flow stayed clean and logical. No more micromanaging tracks. No more nudging audio by a frame.Clips aren’t shackled to rigid tracks. Instead, they're connected in storylines. Modular containers where clips magnetize to one another. Move one, and the rest ripple around it. Dialogue follows picture. Music follows edit. Sync is protected. Instead of scrolling through a mess of layers and keyframes, you're sculpting moments that behave like scenes.At first glance, it looked like chaos. But under the hood, it was something else entirely.Radical. Elegant. Fast. But also deeply polarizing.“Some of those features were controversial even inside the team,” Bayes said. “But we knew we were building something new. Not incrementally better, different.”Instead of ‘bins’, you had Smart Collections. Instead of static timelines, you had dynamic ones.They called it Final Cut Pro X.The 'X' was symbolic. Not just version ten. Not the next chapter. Not a follow-up. A complete reset. An “X” stands for many things. A target. Danger. The one who got away. Or maybe the one who grew up and moved on after the breakup..And at Apple, it was both Steves trying to steer that break.Bayes wasn’t just another product lead in Cupertino. He was just two people removed from Jobs himself. And it was Jobs, famously allergic to legacy systems, who gave the first major greenlight to the FCPX overhaul. “Apple wanted editors to be empowered, mobile, and agile, to edit anywhere, anytime, on their own terms,” Bayes said. “Creativity wasn’t going to live in big studios. It was going to live in backpacks.”Act III: The Day Before Tomorrow - NAB RevealDate: April 12, 2011Location: Las VegasEvent: 10th Annual Supermeet - NAB showThe NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) show is the marquee event for video tech-heads. Think the Olympics, but for video pros who want to show off their finest new tech to the world. The NAB exhibition floor.Typically, the event involves keynote speakers, software demos, and product launches in the exhibition hall. Well, usually… But the 2011 show was different and at the time few people knew why.One of those few was

Eddie is the AI assistant video editor for pros and this week they just launched a trifecta of announcements to bring “ChatGPT” capabilities to Premiere Pro, DaVinci Resolve, and Apple’s Final Cut Pro with their powerful prompt-based AI video editing integrations, which we covered here.

Eddie (the company, not the AI) has also started creating great editorial celebrating the movers and shakers that pushed forward our beloved production industry. See their previous epic narrative about the sunglasses billionaire who founded the RED digital cinema camera here.

This month’s longform article takes a new look at the bombshell that is Final Cut Pro’s migration of 7 to X.

An Untold Look at the “Debacle” of FCP7 to X

April 2011. Las Vegas. A stage. A reveal. A gasp. And then… the fallout.

The launch of Final Cut Pro X didn’t just divide the editing world. It shattered it. Editors fled. Forums exploded. Legacy users cried betrayal. Apple, once the scrappy disruptor-turned-Hollywood darling, suddenly looked like it had fumbled the final reel.

That’s the story. Or was it?

What if the launch of FCPX wasn’t a mistake, but the moment? The moment that, fifteen years later, quietly reshaped how content is created today.

This is the story with new eyes, clarified with the passage of time.

Act I: Ahead of the Timeline

Before Final Cut Pro X, editing was frozen in time.

Things were already digital. But the interface was analog at heart. Tracks. Bins. Timelines that looked like tape. Even Apple’s own Final Cut Pro 7 still clung to analog metaphors.

Enter Steve Bayes, Apple’s Senior Product Manager for Final Cut Pro, and before that, Avid’s first ever instructor. The guy who literally wrote The Avid Handbook. The guy who trained an entire generation of editors on non-linear editors.

He’d seen the old guard, helped build the tools they loved, but knew something needed to change.

“We didn’t want editing to be about operating equipment,” Bayes later said. “We wanted it to be about storytelling.”

But the deeper insight was this: the editor of tomorrow was not sitting in a post house. They were on a laptop, in a bedroom, in a park, with a DSLR and a YouTube login.

Apple didn’t want this user just to be an afterthought, they were the thought.

Act II: The Bet

Apple debated everything. Scrap the timeline? Rethink audio sync? What would an editor’s canvas look like if they weren’t shackled by filmstrips?

Before Final Cut Pro X, editing was like threading tape. Tracks for video. Tracks for audio. Everything had a lane, and moving one clip meant manually pushing or breaking everything else around it.

If you’ve ever knocked your audio out of sync because you slipped one frame too far, you know what I’m talking about.

From those early Apple debates came the Magnetic Timeline.

A new way of editing where clips snapped into place, audio stayed in sync, and the visual flow stayed clean and logical. No more micromanaging tracks. No more nudging audio by a frame.

Clips aren’t shackled to rigid tracks. Instead, they're connected in storylines. Modular containers where clips magnetize to one another. Move one, and the rest ripple around it. Dialogue follows picture. Music follows edit. Sync is protected.

Instead of scrolling through a mess of layers and keyframes, you're sculpting moments that behave like scenes.

At first glance, it looked like chaos. But under the hood, it was something else entirely.

Radical. Elegant. Fast. But also deeply polarizing.

“Some of those features were controversial even inside the team,” Bayes said. “But we knew we were building something new. Not incrementally better, different.”

Instead of ‘bins’, you had Smart Collections. Instead of static timelines, you had dynamic ones.

They called it Final Cut Pro X.

The 'X' was symbolic. Not just version ten. Not the next chapter. Not a follow-up. A complete reset.

An “X” stands for many things. A target. Danger. The one who got away. Or maybe the one who grew up and moved on after the breakup..

And at Apple, it was both Steves trying to steer that break.

Bayes wasn’t just another product lead in Cupertino. He was just two people removed from Jobs himself. And it was Jobs, famously allergic to legacy systems, who gave the first major greenlight to the FCPX overhaul.

“Apple wanted editors to be empowered, mobile, and agile, to edit anywhere, anytime, on their own terms,” Bayes said. “Creativity wasn’t going to live in big studios. It was going to live in backpacks.”

Act III: The Day Before Tomorrow - NAB Reveal

Date: April 12, 2011

Location: Las Vegas

Event: 10th Annual Supermeet - NAB show

The NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) show is the marquee event for video tech-heads. Think the Olympics, but for video pros who want to show off their finest new tech to the world.

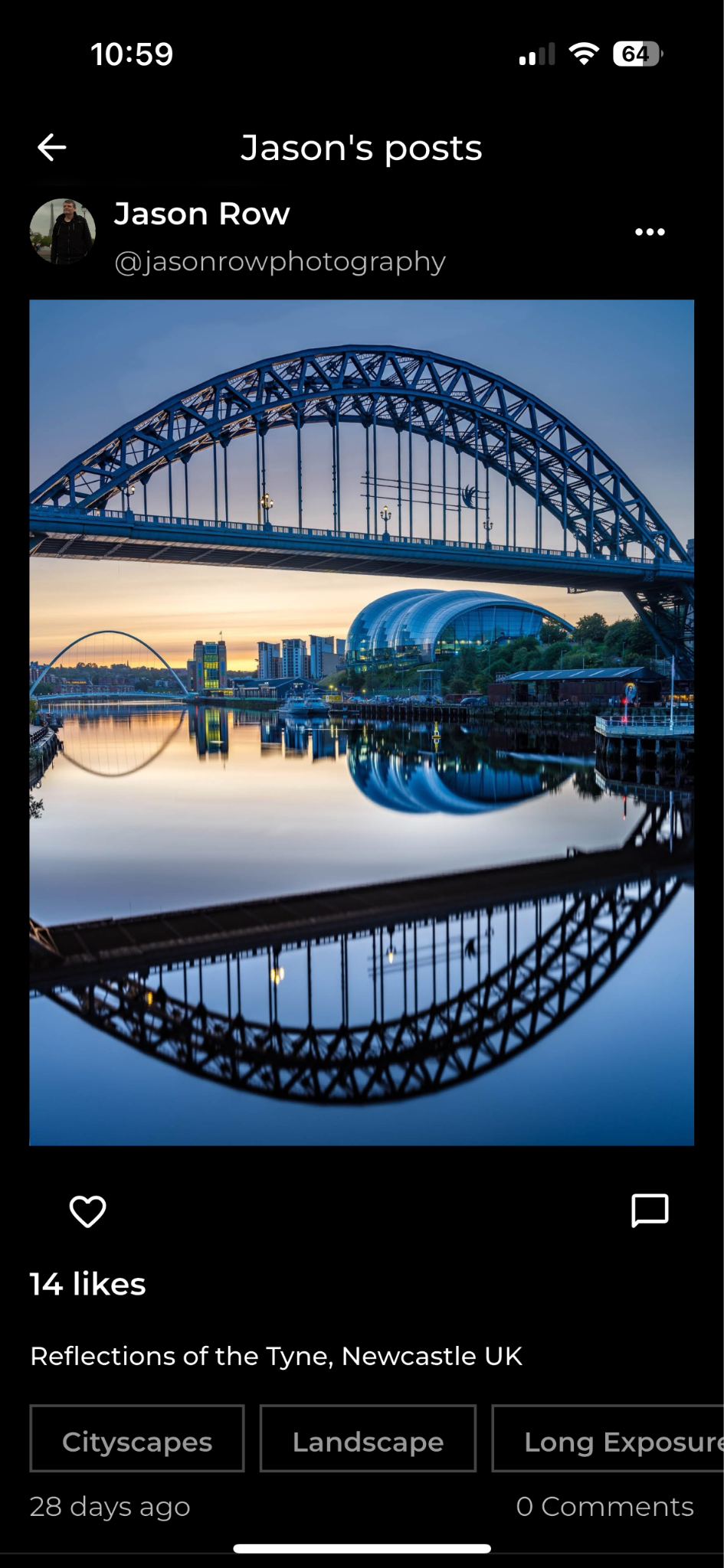

The NAB exhibition floor.

Typically, the event involves keynote speakers, software demos, and product launches in the exhibition hall. Well, usually… But the 2011 show was different and at the time few people knew why.

One of those few was Bill Davis.

He had crossed paths with Steve Bayes over the years as one of the front running Final Cut Pro thought leaders, having spent more than a decade lecturing, contributing, and reporting on all things digital video.

Bill worked the floor at the NAB alongside running his own production company and he started to notice something awry.

Bill recounts, “There were a lot more people than usual crammed on the floor. Hundreds more. Many peculiar figures”.

Bill and his team had frequented NAB for many years meaning there were very few people he didn’t recognize.

There was one lady, in particular, who stood out.

Did she work there? Was she a last-minute technician? A spy?

To continue reading this story, go here.

![‘Blood, Sweat, Tears… and More Blood’ Documents the Making of Indie Horror-Comedy ‘Cannibal Comedian’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cannibalcomedian-mask.jpg)

![Pieces of Masterpieces [MEDEA & SUNDAY]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/medea.jpg)

![American Airlines Offering 5,000-Mile Main Cabin Awards—Because Coach Seats Aren’t Selling [Roundup]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/32387544a799e8261f927c3eb9f4934a-scaled.jpg?#)

![[Expired] 100K Chase Sapphire Preferred Card offer](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/100K-points-offer.jpg?#)

![Air Traffic Controller Claps Back At United CEO Scott Kirby: ‘You’re The Problem At Newark’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/scott-kirby-on-stage.jpg?#)

-Marathon-Gameplay-Overview-Trailer-00-04-50.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Making Brands Relevant: How to Connect Culture, Creativity & Commerce with Cyril Louis](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/cyril-lewis-podcast-29.png)