“True? No. It Happened”: The Beds of Sophie Calle

On June 4, 2025, Notebook will present a screening of Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard’s Double-Blind (1992) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, with special guests Kit Zauhar and Kaitlyn A. Kramer. We hope you’ll join us. Illustration by Zoé Maghamès Peters.Sometimes, when the conversation lags at a social gathering, or when enough empty wine bottles begin to crowd the kitchen counter, I like to ask people to tell me about their childhood bedrooms. I delight in the tinge of embarrassment that colors nostalgia as my friends or acquaintances or (if I’m lucky) strangers recall the period-specific posters adhered to walls with sticky putty, the sheets adorned with cartoon characters, the first kiss beside the nightstand, out of view of a parent’s watchful gaze from the door it was mandatory to leave ajar. A spontaneous anecdote inevitably bursts from these recollections of that singular space where one’s personal expression and preferences were slowly formed. At best, summoning some modicum of the past might just recast the mold of the present moment. That’s what a good story has the power to do, after all.French artist Sophie Calle’s True Stories (Actes Sud, 2023) comprises nothing but. The book’s 66 short stories, each no more than a page in length and accompanied by a photograph, are pithy yet evocative reflections on the various encounters, romances, and disappointments that represent a life in progress (first published in 1994, the book is now in its eighth edition with new stories added to each). These fragments of autobiography are often dramatic and serious, though Calle wholeheartedly embraces the fact that humor often outlines life’s most dire absurdities. On childhood, she offers a story titled “The Bed”: “It was my bed. The one in which I slept until I was seventeen. Then my mother put it in a room she rented out. On October 7, 1979, the tenant lay down on it and set himself on fire. He died. The firemen threw the bed out of the window. It was there, in the courtyard of the building, for nine days.” The photograph depicts a burnt mattress collapsed in a courtyard. While the photograph is hardly remarkable, the image punctuates her shocking story with an exclamation (“Told you so!”) and, in turn, confirms its veracity. “In my work, it is the text that has counted most,” Calle has said. “And yet the image was the beginning of everything.”Two days after her mattress was tossed from the window, on October 9, Calle turned 26, marking the end of a formative year for the artist-to-be. Before True Stories, before she phoned and interrogated the people listed in an address book she found on the street (The Address Book, 1983), before she asked 107 women to interpret a breakup email sent by her ex-lover (Take Care of Yourself, 2007), before inspiring other writers to fictionalize her persona in their novels (Paul Auster’s Leviathan, 1992, and Hervé Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, 1990), Sophie Calle was a bit adrift. Calle’s father, Robert, an art collector and doctor, agreed to house her if she committed to her aspirations of becoming a photographer. So, she wandered around the streets of Paris with her camera, following people throughout the city. One day the following February, she began to follow a man who led her to Venice, where she continued to shadow him for thirteen days. The resulting photographs were collected and narrativized through a series of meticulous diaries and maps in both an exhibition and artist’s book titled Suite Vénitienne in 1983, but first she would return to Paris to distill her impulses into something new.Suite Vénitienne (Sophie Calle, 1983). Courtesy of Siglio.Rather than continue to stalk her prey, she brought the game into her home. Over the course of eight days, from 5 p.m. on April 1 until 10 a.m. on April 9, 1979, Calle arranged a schedule for 27 people to sleep in her bed. While some participants were acquaintances of varying degrees, most were strangers, so she established a scripted questionnaire to present to each sleeper. Calle intended to act as a neutral host, and the questionnaire allowed her to interrogate each guest’s experience with equal weight, whether the sleeper was her mother or a man she was meeting for the very first time. (A surprising few took her up on changing the sheets between visitors.) “Counterpoint to the street,” Andrea Tarsia notes in the “bed” entry of her “Index” on Calle’s work, “they are the site of dispassionate encounters that give rise to a poetry of the everyday.” Once an hour, Calle photographed her visitors’ feet poking through crumpled bedding, their tousled mops of hair, their mouths slightly agape, and their occasional longing gazes—restless, sometimes reading, unable to sleep.The questionnaire, conducted orally and recorded on tape, begins with straightforward information (“Name, age, profession?”) and innocent inquiries about sleep habits (“Does he fall asleep easily?” “When does she prefer to sleep?”) b

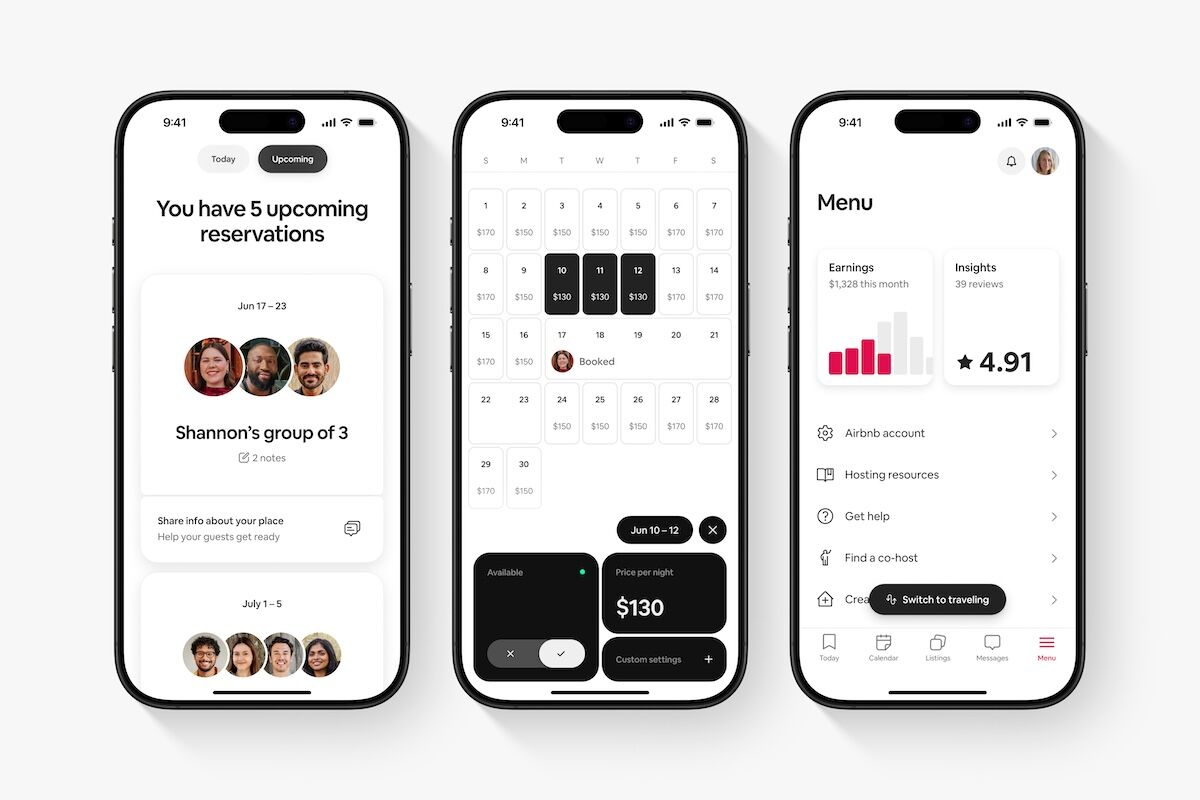

On June 4, 2025, Notebook will present a screening of Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard’s Double-Blind (1992) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, with special guests Kit Zauhar and Kaitlyn A. Kramer. We hope you’ll join us.

Illustration by Zoé Maghamès Peters.

Sometimes, when the conversation lags at a social gathering, or when enough empty wine bottles begin to crowd the kitchen counter, I like to ask people to tell me about their childhood bedrooms. I delight in the tinge of embarrassment that colors nostalgia as my friends or acquaintances or (if I’m lucky) strangers recall the period-specific posters adhered to walls with sticky putty, the sheets adorned with cartoon characters, the first kiss beside the nightstand, out of view of a parent’s watchful gaze from the door it was mandatory to leave ajar. A spontaneous anecdote inevitably bursts from these recollections of that singular space where one’s personal expression and preferences were slowly formed. At best, summoning some modicum of the past might just recast the mold of the present moment. That’s what a good story has the power to do, after all.

French artist Sophie Calle’s True Stories (Actes Sud, 2023) comprises nothing but. The book’s 66 short stories, each no more than a page in length and accompanied by a photograph, are pithy yet evocative reflections on the various encounters, romances, and disappointments that represent a life in progress (first published in 1994, the book is now in its eighth edition with new stories added to each). These fragments of autobiography are often dramatic and serious, though Calle wholeheartedly embraces the fact that humor often outlines life’s most dire absurdities. On childhood, she offers a story titled “The Bed”: “It was my bed. The one in which I slept until I was seventeen. Then my mother put it in a room she rented out. On October 7, 1979, the tenant lay down on it and set himself on fire. He died. The firemen threw the bed out of the window. It was there, in the courtyard of the building, for nine days.” The photograph depicts a burnt mattress collapsed in a courtyard. While the photograph is hardly remarkable, the image punctuates her shocking story with an exclamation (“Told you so!”) and, in turn, confirms its veracity. “In my work, it is the text that has counted most,” Calle has said. “And yet the image was the beginning of everything.”

Two days after her mattress was tossed from the window, on October 9, Calle turned 26, marking the end of a formative year for the artist-to-be. Before True Stories, before she phoned and interrogated the people listed in an address book she found on the street (The Address Book, 1983), before she asked 107 women to interpret a breakup email sent by her ex-lover (Take Care of Yourself, 2007), before inspiring other writers to fictionalize her persona in their novels (Paul Auster’s Leviathan, 1992, and Hervé Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, 1990), Sophie Calle was a bit adrift. Calle’s father, Robert, an art collector and doctor, agreed to house her if she committed to her aspirations of becoming a photographer. So, she wandered around the streets of Paris with her camera, following people throughout the city. One day the following February, she began to follow a man who led her to Venice, where she continued to shadow him for thirteen days. The resulting photographs were collected and narrativized through a series of meticulous diaries and maps in both an exhibition and artist’s book titled Suite Vénitienne in 1983, but first she would return to Paris to distill her impulses into something new.

Suite Vénitienne (Sophie Calle, 1983). Courtesy of Siglio.

Rather than continue to stalk her prey, she brought the game into her home. Over the course of eight days, from 5 p.m. on April 1 until 10 a.m. on April 9, 1979, Calle arranged a schedule for 27 people to sleep in her bed. While some participants were acquaintances of varying degrees, most were strangers, so she established a scripted questionnaire to present to each sleeper. Calle intended to act as a neutral host, and the questionnaire allowed her to interrogate each guest’s experience with equal weight, whether the sleeper was her mother or a man she was meeting for the very first time. (A surprising few took her up on changing the sheets between visitors.) “Counterpoint to the street,” Andrea Tarsia notes in the “bed” entry of her “Index” on Calle’s work, “they are the site of dispassionate encounters that give rise to a poetry of the everyday.” Once an hour, Calle photographed her visitors’ feet poking through crumpled bedding, their tousled mops of hair, their mouths slightly agape, and their occasional longing gazes—restless, sometimes reading, unable to sleep.

The questionnaire, conducted orally and recorded on tape, begins with straightforward information (“Name, age, profession?”) and innocent inquiries about sleep habits (“Does he fall asleep easily?” “When does she prefer to sleep?”) before veering into probing (“Does he remember ever peeing the bed?”) and provocation (“Does she masturbate? If so, at night or in the morning?”). On several occasions, Calle asked her bedfellows if they dream, recalling Agnès Varda’s wistful prompt to her neighboring shopkeepers on Rue Daguerre in her loving documentary Daguerréotypes (1975). It was in a market on Rue Daguerre where Calle met one of her participants, who happened to be married to the art critic Bernard Lamarche-Vadel. Upon seeing the photographs of Calle’s sleepers, he proposed exhibiting them in the Paris Biennale at the Musée d’Art Moderne. The 176 photographs and 23 texts transcribed from the audiotapes became Les dormeurs (The Sleepers), and Calle an artist on her own terms.

The Sleepers (Sophie Calle, 1979). Courtesy of Siglio.

Calle’s early works were primarily displayed as installations, but it didn’t take long for her to find a more appropriate form to hold her words and images in tandem: the artist’s book. Since 2012, Calle has worked in close collaboration with the art book publisher Siglio to create English-language editions, translated from the original French. Calle’s books with Siglio are events—sumptuous and vivid in their compact presentations—and the newly published edition of The Sleepers is perhaps the greatest yet. A sacred experience is offered by beholding a Calle artist’s book, which can read like a secret revealed through a peephole. The writer Sheila Heti compared reading one of her books to scarfing a bag of potato chips, so wicked is her momentum as she violates the privacy of strangers, but so delicious. With The Sleepers, I found the sensation akin to the pull of eavesdropping. As an object, the book winks at its subject; the plush, clothbound cover almost comically recalls the shape and texture of a pillow. Pressing onto the book’s soft texture, I think of Robert Rauschenberg and his Bed (1955). Rauschenberg frequently incorporated found objects into his paintings and, one summer day, decided he no longer needed his quilt, that it would be better served as a canvas. He affixed the quilt to the stretcher bars and began painting but felt that no matter what he did to intervene, and regardless of the quilt’s abstract pattern, the painting wanted to be a bed. “So, finally,” he recalled, “I gave in and I gave it a pillow.”

Beds are a persistent, almost compulsive, theme in Calle’s work. On October 5, 2002, she spent the night in a bed on top of the Eiffel Tower, where strangers were instructed to keep her awake by telling her stories. As always with Calle, there were rules: “Maximum length: 5 minutes. Longer if thrilling. No story, no visit. If your story sends me to sleep, please leave quickly and ask the guard to wake me.” Three years earlier, she received a letter from a man in California. Heartsick from a breakup, he asked if he might spend the remainder of his mourning period in her bed. Since there was “already a man in [her] bed,” as she recounts in True Stories, she decided to ship her bed to the grieving stranger. A few months later, no longer in pain, he returned the bed back to Calle. As simple as that. When exhibited, Journey to California (2003) includes Calle’s characteristic documentation (emails, photographs of the mattress at various points in the voyage) in addition to the wrapped bundle of her mattress and bedding sent by and returned to Calle. Reading these tales sometimes feels like a fever dream. Calle’s language is so assured and honest, I’ve stopped second-guessing any of her actions. Naturally, when propositioned, it makes sense to ship one’s mattress to a strange man. Of course. In the catalogue of the recent exhibition Sophie Calle: Overshare at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, curator Courtenay Finn observes Calle as a character, offering the poignant conclusion that “after all, stories, whether real or imaginary, must be told by someone, and even facts need a narrator.”

Journey to California (Sophie Calle, 2003). Installation view of Sophie Calle: Overshare. Photograph by Eric Mueller. Courtesy of Walker Art Center.

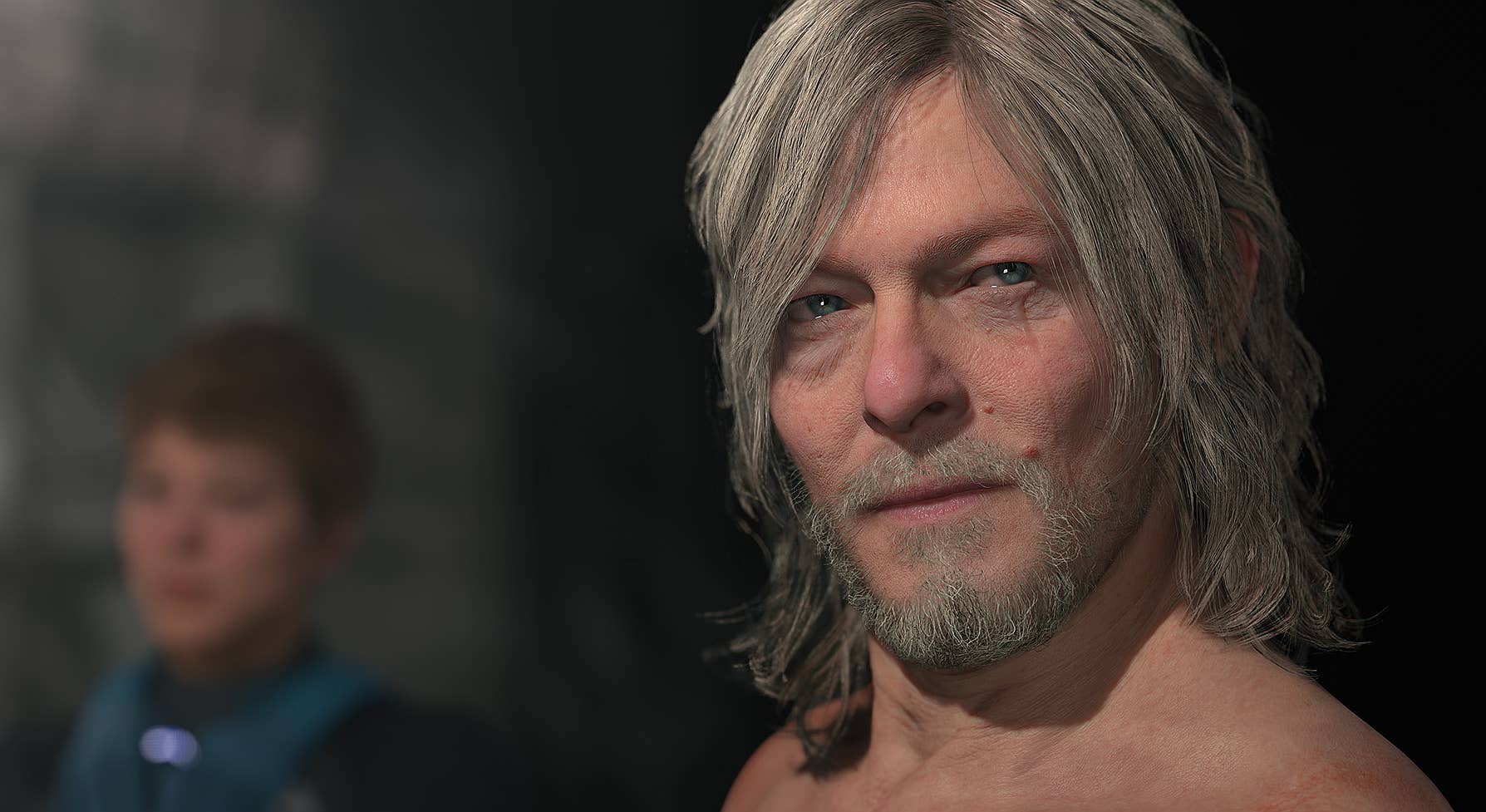

In the film Double-Blind (also known as No Sex Last Night, 1992), Calle conspires with a co-narrator to play another game. The film follows Calle and her brooding would-be lover on a cross-country road trip as everything—the car, the relationship, time—consistently breaks down. Calle met Greg Shephard in December 1989 in a New York bar, where he offered to host her that night. He gave her the keys and she went but, when he failed to show up at home, she spent the night alone in his bed. As she tells it in True Stories, “The only thing I learned about him came from a piece of paper that I found under a cigarette box. It said: ‘Resolutions for the New Year: no lying, no biting.’” The new year came and went and, after an aborted rendezvous at the Orly Airport, the dysfunctional pair finally found each other when Shephard phoned Calle from Orly, nearly a year late. Shephard, a small-time art dealer, aspired to become a filmmaker, and Calle aspired to become his wife, so she devised a compromise in the form of a road trip. With two video cameras in tow, they would drive Shephard’s Cadillac DeVille from New York to California, where Calle had accepted a teaching job, with a stopover in Las Vegas to be wed, each filming the events from their own perspective.

It was a mess from the start. Shephard, depressed and in love with another woman, fails to fix up the car before Calle arrives from Paris and it immediately breaks down, resulting in costly repairs almost daily. Meanwhile Calle, grieving the recent death of her dear friend, the writer Hervé Guibert, retreats inward. For the first few days, hardly a word is spoken between the two. Their overwhelming emotions are revealed through voiceover narration recorded by their cameras’ onboard microphones, typically in the other’s presence. Calle benefits from speaking her mind in her native French, which Shephard does not understand, but he often resorts to delivering his regrets in a whisper, holding the camera to his mouth, his tone betraying various levels of honesty, both with himself and with Calle, despite his resolution. One early setback which ultimately proved beneficial to the film was the couple’s inexperience operating their handheld cameras. Watching the tapes back a few days in, they feared the trip had already failed. While the footage shot in the car was satisfactory, they found what they recorded outside the car—at the mechanic, in restaurants and hotels—to be shaky and distractingly erratic. Calle, inspired by Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), determined that the film would combine still and moving images, a decision that offers a levity to the story, at once melancholic and playful (the film includes dedications to both Guibert and Marker in the credits). The couple record one another in various hotel rooms over the fifteen nights of the trip, each expressing their frustrations and dissatisfactions. These scenes always end with a still of morning light on the unmade bed they’ve shared, and a voiceover from Calle: “No sex last night,” or simply “No.”

After many nights of this, with Shephard biting his fingers, hands, and arms all the while, Calle appears weary. When her motives are betrayed, she tends to fixate on specific details. In The Sleepers, the experiment begins to break apart when some participants show up late or, in a few cases, not at all. Calle assumes the place of these delinquent sleepers, but the disappointment takes a toll. She becomes obsessed with ensuring the bed is constantly occupied, at times privileging it over the structure of the questionnaire, which she begins to consider by that point “a diversion.” During the visit of the twenty-fifth sleeper, a journalist for Libération, she writes of her own experience, “I talk about the ritual, which is petering out despite the acquired expertise. Sometimes I forget the aloof demeanor that I had set for myself. The questions, the photos matter less to me. My concerns become more defined, narrow. Sole necessity: the occupation of the bed. Empty, it bothers me.” Even as Shephard repeatedly borrows money from Calle to call another woman from gas-station pay phones, she can’t let go of her marriage plans. Just as the bed remained occupied in one way or another, Shephard ultimately concedes to the wedding, the bastard. And the scene is surprisingly touching, though it takes place at a 24-hour drive-through chapel. They position the camera behind the car as they exchange vows, mostly drowned out by the sound of the traffic along the strip, and they look happy. The morning after next, over an image of that night’s bed, Calle tells us, “Yes.” But the story doesn’t end there.

Double-Blind (Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard, 1992).

Calle and Shephard stayed married during (and in large part because of) the film’s editing process, through which Calle found that, unlike her previous work dictated by her predetermined rules, she had more control over how the story was told. The title refers to a double-blind study, where neither the participants nor the researchers know who is the test group or the control group until after the experiment ends—an apt metaphor for filmmaking. She later reflected on the editing process and how it complicates the concept of “truth” in the film: “We chose to put the emphasis on me and my solitude and him and his car, whereas we could have chosen to speak only about food, or only about traveling cross-country, or only about the disgust we had for each other, or only about the beautiful moments we shared. So any one version is never ‘true,’ it just works better than another. But I can say that it did happen. True? No. It happened.” Film becomes a medium for Calle to control her motives and their effects; in arranging the images and words of what “happened,” she lands on something personal—something real.

Double-Blind begins and ends with subtle motion unfolding within a small rectangular box in the center of the screen, a thick black border obscuring the majority of the frame. It’s a disorienting device made even more perplexing when Calle begins to speak, introducing her relationship to Shephard over all that black space. I found myself leaning in, wanting more than I was given. A good storyteller knows to string her listener along, to give her tunnel vision as carefully crafted details rush by. There’s a story in True Stories titled “The Other,” about Calle’s experience sleeping with another man while still heartbroken over Shephard, accompanied by the image of a closed eye, framed by total darkness like the moving images in the film. This story includes the only sentence in the book that Calle didn’t write herself, a quote by Rainer Maria Rilke: “What happens is always so far ahead of us, that we can never catch up to it and know its true appearance.” Nonetheless, we follow life forward, through the black.

![‘Mortal Kombat 1: Definitive Edition’ Now Available [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/mk1definitive.jpg)

![Invitation to the Trance [SLEEPWALK]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/sleepwalk2.png)

![Real Horror Shows [EYES WITHOUT A FACE & THE KINGDOM]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/eyes-without-a-face-belgian-poster.jpg)

![‘Sound Of Falling’ Review: The Body Keeps The Score In Mascha Schilinski’s Hotly Anticipated Competition Contender [Cannes]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/14133225/SOUND-OF-FALLING-Mascha-SCHILINSKI-Photos-4-Films-kit.jpg)