This Italian Town Really, Really Likes Ocarinas

For thousands of years, humans across the world have played music using some version of the ocarina, a rounded wind instrument that produces a flute-like sound. In ancient China, ocarina-like instruments date back to 5,000 BC, and the Maya and the Aztecs used them in religious ceremonies. But the modern ocarina, a sweet potato–shaped instrument with 10 to 12 holes, was invented, by mistake, in the small Italian town of Budrio. Today, that same town is host to the world’s largest ocarina festival. In 1853, Giuseppe Donati, a 17-year-old boy from Budrio, spent his time messing around with clay. “Donati used to play the clarinet in the town’s band,” says Christian Paolini, a tour guide at Budrio’s Ocarina Museum. ”He used to make make-shift instruments for his bandmates.” For one of his experiments, Donati set out to craft a whistle with a rounded base and a curved bell, like a trumpet. But while handling the clay prototype, he accidentally cracked the “neck” of the bell. “He tried playing the bottom part of the instrument and realized that it produced an interesting sound,” Paolini says. In the years that followed his accidental invention, Donati perfected the design of the instrument, which he referred to as an ucarina, “small goose” in the local dialect. He devised a set of five ocarinas that produced a range of low-pitched to high-pitched notes. In 1863, Donati and his fellow musicians formed Budrio’s first ocarina quintet. “Donati’s idea of creating a set of five ocarinas dramatically expanded the instrument’s musical reach,” Paolini says. “The quintet could play quite a diverse range of music, from folk songs to opera themes.” Over the years, the group added two more ocarinas and the quintet became a septet. In 1869, Budrio’s ocarina players performed at a theater in Bologna. The septet played a selection of themes from some of the most famous operas of the time, from Verdi’s La Traviata to Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. “The public loved it,” Paolini says. “The theater manager was so impressed that booked them again.” Word about this unusual music based on a “humble” instrument from Budrio got around. In the following months, Budrio’s ocarina group toured major Italian cities such as Padua, Udine, and Ferrara. By the 1870s, the band was playing the most important European capitals like Vienna, Paris, and London. In 1874, the London Daily News reported on a concert held by the Budrio’s ocarina band at Crystal Palace, noting that the William Tell Overture was performed “with the same intensity and precision of a full orchestra.” At the time, the band was playing under the stage name the Montagnards des Appenines, the “mountain people from the Apennines," and wearing traditional shepherd costumes to perform. “Imagine seeing a group of seven men dressed like shepherds, playing opera themes with clay instruments, inside one of London’s most up-and-coming theatres,” Paolini says. “That must have been quite a scene.” Many other Budrio residents, or Budriesi, also played a role in the ocarina’s unexpected success. Cesare Vicinelli, a member of Budrio’s original ocarina quintet, invented the first metal molds for ocarinas, producing instruments with a bright and clear sound. “He was considered the Stradivari of ocarinas,” Paolini explains. Alberto and Ercole Mezzetti, also members of the band, exported Budrio’s “little goose” beyond Italy. Ercole opened an ocarina workshop in Paris in 1877, winning medals for his innovative designs at the 1878 and 1900 World Expositions. His brother Alberto moved to London in 1879 and became a music teacher and editor of exercise books for ocarina students. “The story of the ocarina is the story of how Budrio gets on the world’s map,” Paolini says. Ocarinas designed and crafted by generations of Budriesi are now kept in the town’s two-story Ocarina Museum. One exhibit is dedicated to the local craftsmen who have innovated on Donati’s invention. One of those craftsmen is Fabio Menaglio, who crafts ocarinas by hand in his workshop in Budrio. First, he models clay to make two pieces, the “head” and the body” of the ocarina. Then, he glues them together using slip, or liquid clay, and adds holes in the side of the ocarina using the tip of a drill. Menaglio leaves the ocarinas to air-dry on a wooden shelf, and later bakes them in a kiln. While drying and baking, the ocarina can shrink, so making sure to account for that while modeling the clay is a vital part of the process. Menaglio calls himself a "craftsman of sound.” Each step of the ocarina-making process can affect how the instrument sounds, he explains. Small and elongated bodies make higher-pitched sounds, while larger and thicker ones emit lower-pitched sounds. Even when making ocarinas of the same variety, small differences in the inner volume of the body can produce different sounds. “We still make each instrument by hand, so naturally they are not exactly the same,” he explains. “My job is to make them as

For thousands of years, humans across the world have played music using some version of the ocarina, a rounded wind instrument that produces a flute-like sound. In ancient China, ocarina-like instruments date back to 5,000 BC, and the Maya and the Aztecs used them in religious ceremonies.

But the modern ocarina, a sweet potato–shaped instrument with 10 to 12 holes, was invented, by mistake, in the small Italian town of Budrio. Today, that same town is host to the world’s largest ocarina festival.

In 1853, Giuseppe Donati, a 17-year-old boy from Budrio, spent his time messing around with clay. “Donati used to play the clarinet in the town’s band,” says Christian Paolini, a tour guide at Budrio’s Ocarina Museum. ”He used to make make-shift instruments for his bandmates.” For one of his experiments, Donati set out to craft a whistle with a rounded base and a curved bell, like a trumpet. But while handling the clay prototype, he accidentally cracked the “neck” of the bell. “He tried playing the bottom part of the instrument and realized that it produced an interesting sound,” Paolini says.

In the years that followed his accidental invention, Donati perfected the design of the instrument, which he referred to as an ucarina, “small goose” in the local dialect. He devised a set of five ocarinas that produced a range of low-pitched to high-pitched notes. In 1863, Donati and his fellow musicians formed Budrio’s first ocarina quintet. “Donati’s idea of creating a set of five ocarinas dramatically expanded the instrument’s musical reach,” Paolini says. “The quintet could play quite a diverse range of music, from folk songs to opera themes.” Over the years, the group added two more ocarinas and the quintet became a septet.

In 1869, Budrio’s ocarina players performed at a theater in Bologna. The septet played a selection of themes from some of the most famous operas of the time, from Verdi’s La Traviata to Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. “The public loved it,” Paolini says. “The theater manager was so impressed that booked them again.” Word about this unusual music based on a “humble” instrument from Budrio got around.

In the following months, Budrio’s ocarina group toured major Italian cities such as Padua, Udine, and Ferrara. By the 1870s, the band was playing the most important European capitals like Vienna, Paris, and London. In 1874, the London Daily News reported on a concert held by the Budrio’s ocarina band at Crystal Palace, noting that the William Tell Overture was performed “with the same intensity and precision of a full orchestra.” At the time, the band was playing under the stage name the Montagnards des Appenines, the “mountain people from the Apennines," and wearing traditional shepherd costumes to perform. “Imagine seeing a group of seven men dressed like shepherds, playing opera themes with clay instruments, inside one of London’s most up-and-coming theatres,” Paolini says. “That must have been quite a scene.”

Many other Budrio residents, or Budriesi, also played a role in the ocarina’s unexpected success. Cesare Vicinelli, a member of Budrio’s original ocarina quintet, invented the first metal molds for ocarinas, producing instruments with a bright and clear sound. “He was considered the Stradivari of ocarinas,” Paolini explains. Alberto and Ercole Mezzetti, also members of the band, exported Budrio’s “little goose” beyond Italy. Ercole opened an ocarina workshop in Paris in 1877, winning medals for his innovative designs at the 1878 and 1900 World Expositions. His brother Alberto moved to London in 1879 and became a music teacher and editor of exercise books for ocarina students. “The story of the ocarina is the story of how Budrio gets on the world’s map,” Paolini says.

Ocarinas designed and crafted by generations of Budriesi are now kept in the town’s two-story Ocarina Museum. One exhibit is dedicated to the local craftsmen who have innovated on Donati’s invention. One of those craftsmen is Fabio Menaglio, who crafts ocarinas by hand in his workshop in Budrio. First, he models clay to make two pieces, the “head” and the body” of the ocarina. Then, he glues them together using slip, or liquid clay, and adds holes in the side of the ocarina using the tip of a drill. Menaglio leaves the ocarinas to air-dry on a wooden shelf, and later bakes them in a kiln. While drying and baking, the ocarina can shrink, so making sure to account for that while modeling the clay is a vital part of the process.

Menaglio calls himself a "craftsman of sound.” Each step of the ocarina-making process can affect how the instrument sounds, he explains. Small and elongated bodies make higher-pitched sounds, while larger and thicker ones emit lower-pitched sounds. Even when making ocarinas of the same variety, small differences in the inner volume of the body can produce different sounds. “We still make each instrument by hand, so naturally they are not exactly the same,” he explains. “My job is to make them as consistent as possible so that musicians can harmonize their sound more easily.” According to Paolini, Menaglio has gained a reputation as an “ocarina wizard” for the consistency of his instruments.

Along with ocarinas, Budrio also produces people who love to play them. In fact, the town still boasts a touring ocarina orchestra. Members of the current ocarina septet, known as the Gruppo Ocarinistico Budriese, get their ocarinas from Menaglio. Whenever they get new instruments, they’ll spend weeks together practicing their harmonies. “That’s what I love the most about playing the ocarina,” says Leonardo Carbone, the youngest member of the GOB. “It takes a lot of practice to reach a harmonized sound, but when you do it’s magical.”

In the past 15 years, Budrio’s ocarina septet has ventured beyond Europe. In China, Japan, and South Korea, their tours are always sold out. Part of the band’s success in East Asia goes back to the long-standing tradition of ocarina-like instruments in those countries. “If you listen to a concert by the GOB, it has a similar sound to traditional Taoist music,” Paolini says. But some of their appeal is a more recent phenomenon. Emiliano Bernagozzi, part of the GOB since the 1990s, says that the band first went to South Korea in 2010 for a concert. At the time, ocarinas were gaining traction in the country, transitioning from little-known instruments to a popular way to teach music in schools. The group was approached by local businessmen who loved their music so much that they offered to sponsor a national tour. The band’s entry into Japan followed a similar trajectory. “We were scouted by a PR firm that wanted to promote our music,” Bernagozzi says. “Now our performances at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre are always sold out.”

In recent years, the ocarina has also become a well-known instrument in North America. Many people in the gaming community discovered the instrument thanks to the 1998 video game The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, where the player can solve puzzles by playing an ocarina. The US now has its first ocarina septet, Ocabanda, that performs traditional ocarina pieces as well as anime and video game themes.

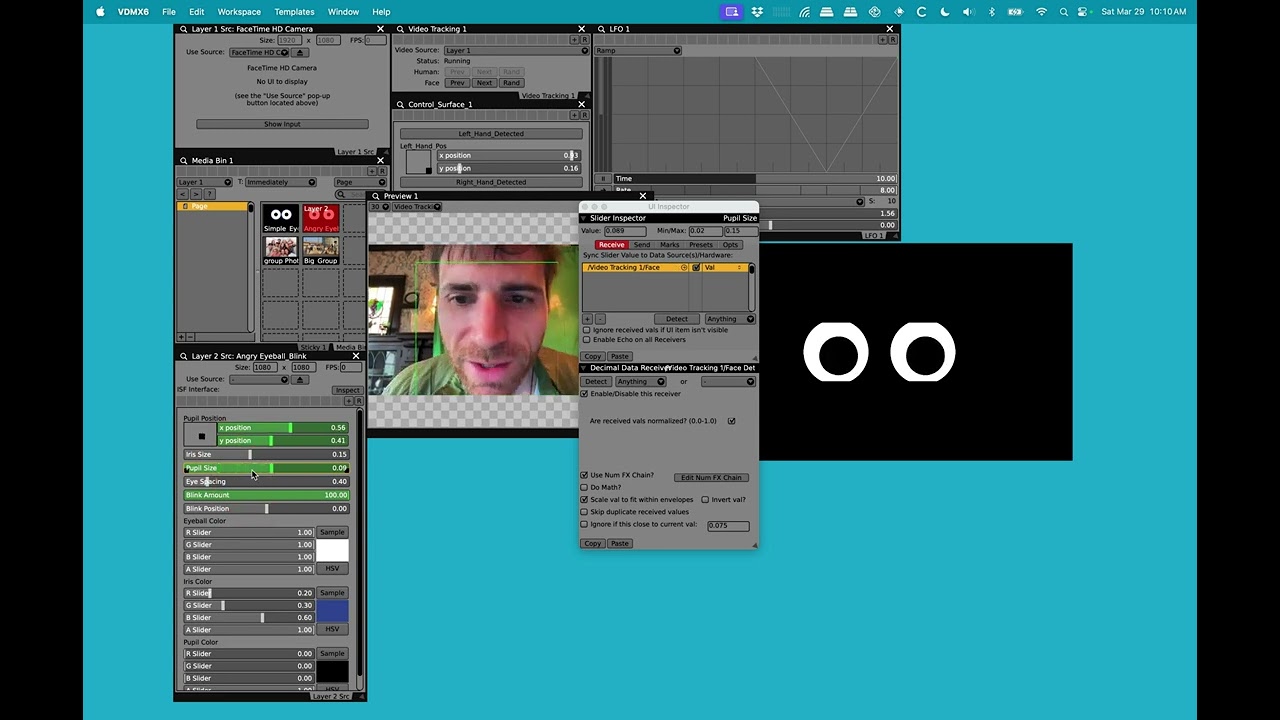

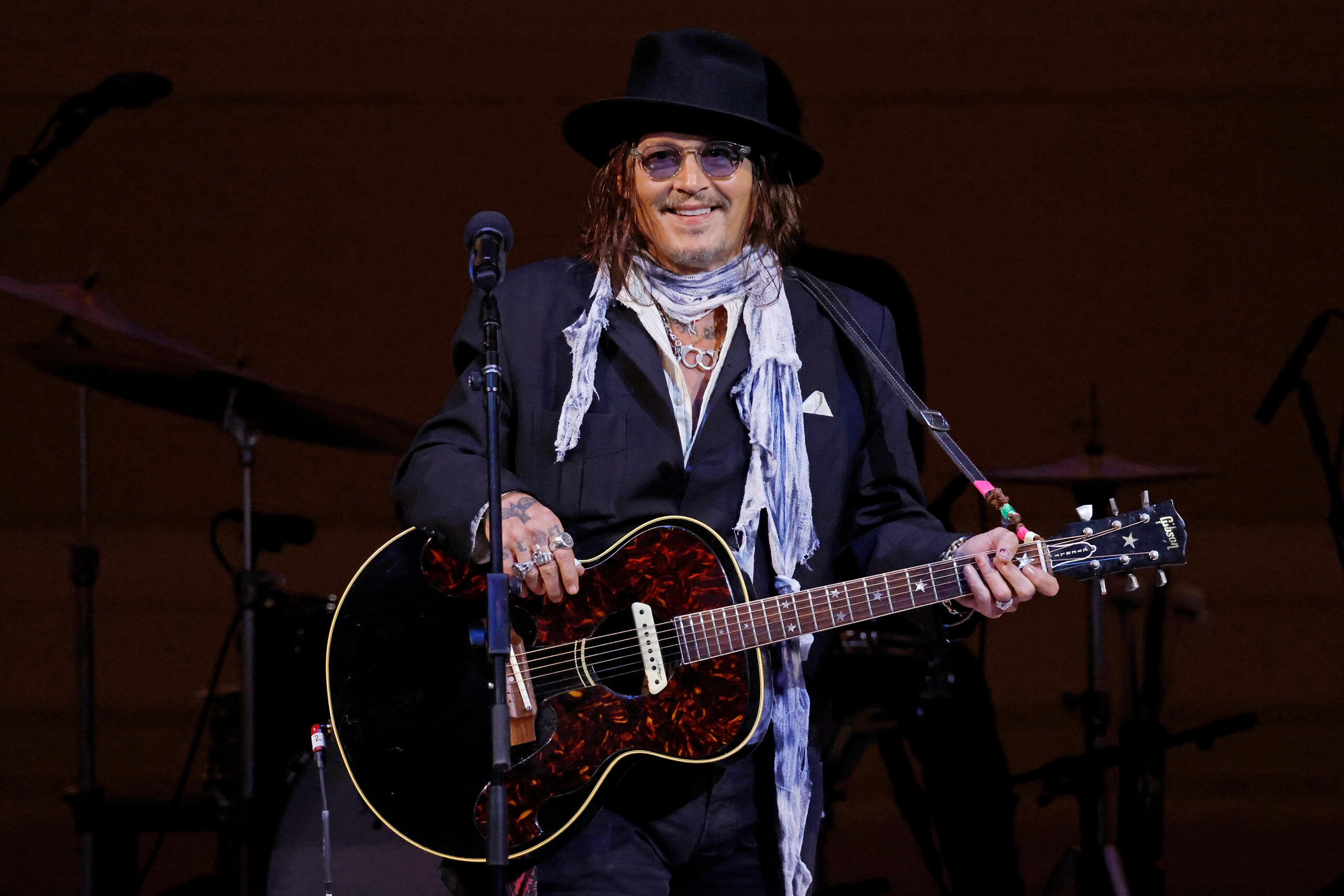

Every year, in mid-April, the world’s ocarina-lovers descend on Budrio for the International Ocarina Festival. This year, organizers expect about a hundred artists from around the world to take part in live performances, talks, and workshops. “We are very proud of how this festival has become a gathering for ocarina and music lovers at large,” says Budrio’s mayor Debora Badiali. She adds that spontaneous encounters between ocarina players, craftsmen, and fans often give rise to unexpected partnerships, like in the case of electronic musician Godblesscomputers, who, at this year’s festival, will perform a live DJ set mixing electronic and ocarina music.

The town’s next goal is to further cement Budrio’s role as the epicenter of the global ocarina scene. Two years ago, nearby Bologna’s music conservatory, Conservatorio G. B. Martini, launched the world’s first official course in ocarina music. And officials are now discussing the creation of apprenticeships to teach the traditional craft of ocarina-making. “Since its invention, the ocarina has been the link between local heritage and the world,” Badiali says, “We want to promote our city as the place where anyone interested in this instrument comes to learn about it.”

![Maintain Your Sanity Against Lovecraftian Horrors in ‘Static Dread’ This August [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/staticdread.jpg)

![The Top 10 “Invisible” Movies of All Time (We Think) [Halloweenies Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/invisible-movies.jpeg)

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Bright Spots in the Darkness [My 1998 Top Ten List]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/rochefort.jpg)

![Watch: Bag Breaks Loose on Southwest Tarmac—Drives in Circles Like It’s Alive [Roundup]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/332262b7f684b362d1b73b98ae6249f8.jpg?#)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_site.jpg)