Charting the Conflicts of American Democracy Through Henry Fonda’s Career

Henry Fonda for President envisions American history through the dual lives of Henry Fonda: the movie star and the real man behind him. While it’s the debut film from 61-year-old director Alexander Horwath, following his many years as a critic and programmer of the Austrian Film Museum, a lifetime of cinephilia and hard work lie behind it. […] The post Charting the Conflicts of American Democracy Through Henry Fonda’s Career first appeared on The Film Stage.

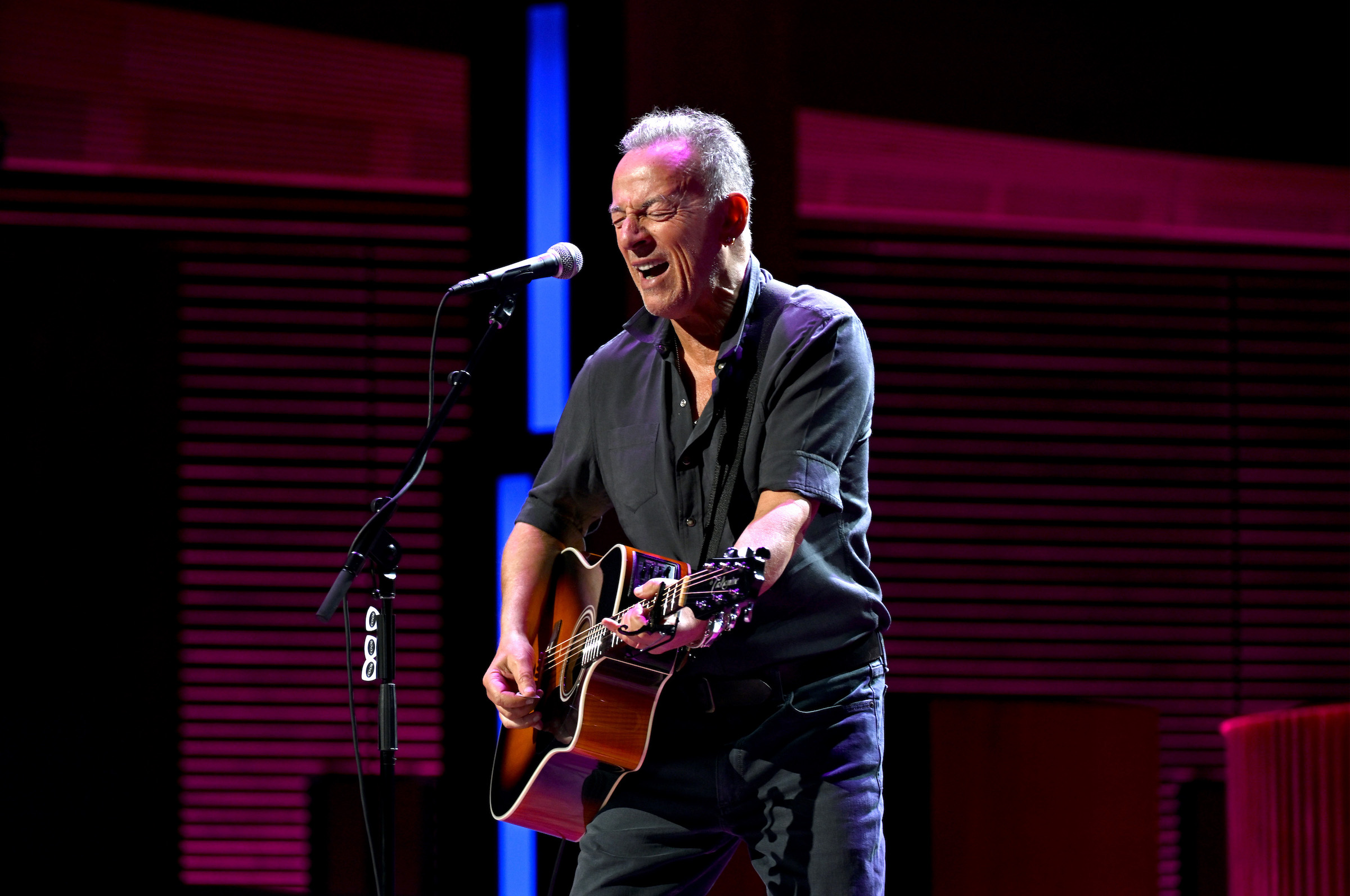

Henry Fonda for President envisions American history through the dual lives of Henry Fonda: the movie star and the real man behind him. While it’s the debut film from 61-year-old director Alexander Horwath, following his many years as a critic and programmer of the Austrian Film Museum, a lifetime of cinephilia and hard work lie behind it. Horwath’s engagement with Fonda’s films began with a trip to Paris in 1980. In Fonda, Horwath finds a defensible version of the U.S. (The film quotes James Baldwin to the effect that Fonda was the only white actor he admired.) Henry Fonda for President contrasts Fonda’s image with the rise of Ronald Reagan. Its montage brings together movie clips, footage shot in the U.S. by this film’s team, and audio excerpts from an exhaustive 1981 interview with Fonda.

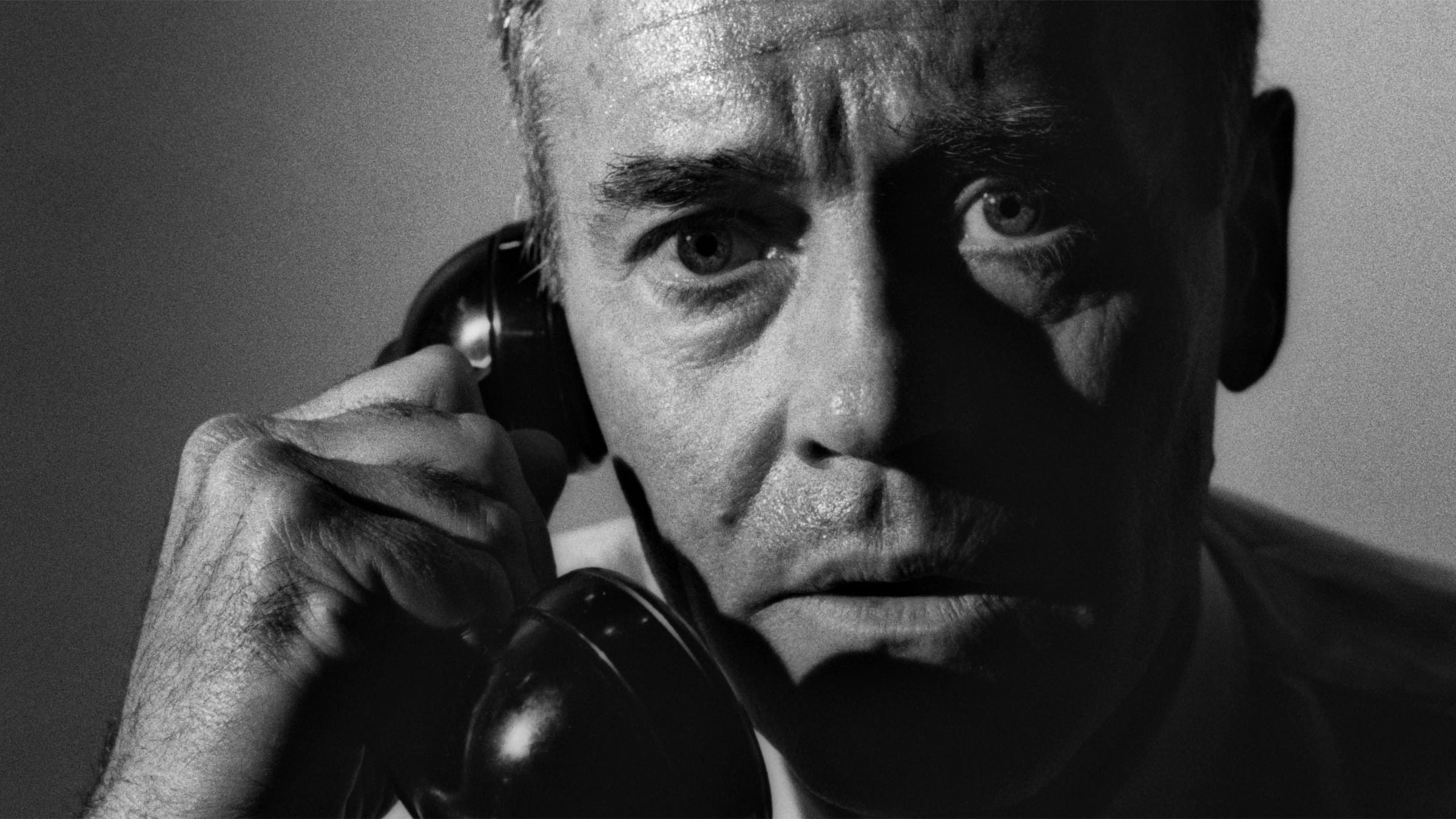

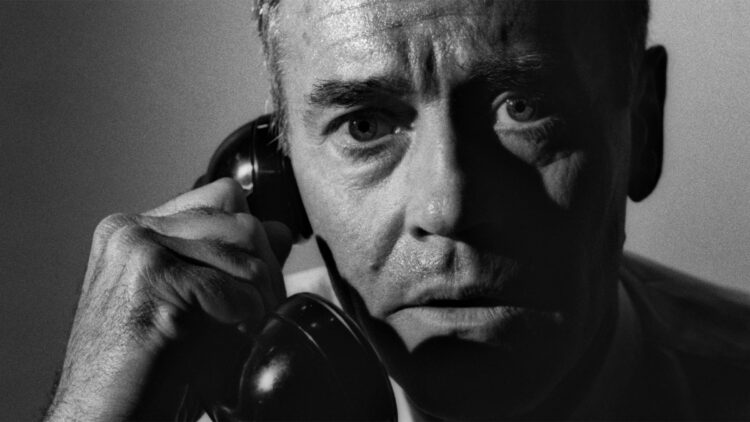

The three-hour journey is an ambitious project that uses cinema to critique both itself and the larger world, a la Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself. Horwath returns to the concept of chiaroscuro as a key characteristic of Fonda, showing several shots in which part of his face is covered. This notion literally gets past black-and-white thinking, letting nuance and humility enter the picture. A vision of America as wholly mediated, with John Hinckley Jr. (now performing folk music on his YouTube channel) and TV character Maude as equal participants, runs through the film. Does it matter that only one of those people is fictional? In the end, Henry Fonda for President retains a respect for the possibilities American life could have offered, as it points out this country’s numerous flaws. Fonda’s self-doubts and imposter syndrome let the reality behind images of America show through.

Shortly before the New York premiere of Henry Fonda for President at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight, The Film Stage spoke with Horwath via Zoom from his home in Vienna. Henry Fonda for President opens at Anthology Film Archives on Thursday, April 3 and will expand.

The Film Stage: There’s a tradition in Austria of films made in response to Hollywood, going from Funny Games to Martin Arnold and Peter Tscherkassky’s shorts. Do you see Henry Fonda for President as a part of that?

Alexander Horwath: I have not thought along those lines, but I agree about that tradition. It covers a wide range, from Haneke to experimental films, and our film is not close to either. If you look at it on a wider scale, all smaller nations’ cinema has a tendency to position themselves and their practice in relation to Hollywood. It’s not just an Austrian thing. If they strive for an autonomous cinema, they see themselves as opposing Hollywood because it has dominated the Western world’s screens for such a long time. Any form of art film must deal with this dominant presence. That would go for both Haneke and experimental films.

In our case, it’s not an attempt to distance ourselves from Hollywood but to relate to it in a specific manner. My own interest in American cinema goes back a very long time. Like a lot of European cinephiles, my experiences have been shaped by American culture’s presence in our discourse. It’s an attempt to communicate with that tradition, but not necessarily a break. It takes American cinema’s legacy as a subject, but I hope it makes clear that it’s not coming from the U.S.––that’s why there’s no English-language version. I’ve been asked if there will be a version where I speak the voice-over in English. I never wanted that, because it was important to make clear to any viewer in the world that it comes from a different place. It was important for the German language to have a presence. That’s also one of the reasons I included Hannah Arendt and Günther Anders’ audio quotes, although not the only one.

There’s also a distance to the way you film America. You don’t interview any Americans, and you shoot roadsides in long shots. Was that also a way of establishing your difference?

I made certain preliminary choices. There would be no talking-head interviews. The three of us––Michael Palm, Regina Schlagnitweit, and myself––went through several years making this film. It would not consist of conversations, although we did talk to people a lot during our trips to America. But we made it clear that it was for our own purposes and would never be part of the film onscreen. Second: the choice of locations was highly prescribed by the places in Fonda’s own biography and the biographies of his screen characters. We chose many locations in the Midwest. The way we represented those places comes from an American tradition, but not Hollywood. You can connect it to an avant-garde and essay-film tradition––with Thom Andersen, John Gianvito, and James Benning, for instance. We did not consciously choose to follow that path, but our general decisions about representing these landscapes was strongly informed by that tradition. It’s not only an American one––you can think of some Chantal Akerman films.

Are there any other actors you could have made a film about?

First of all, I should say I was not planning to become a filmmaker when I stopped working at the Austrian Film Museum after 16 very intense years. I would do whatever came along. There are two producers––an Austrian one and German one. Irene Höfer, whom I had known for years, came up with the idea that I should direct a film about film history. I was very skeptical, since I hadn’t made films before. It took me several steps to feel more secure in this new role, but I’m happy now that I took the jump. The thing that made me tell her “OK” is that the subject of Henry Fonda and America was seductive to me. As the film shows, I was already interested in him as a teenager. The last program I did for the Austrian Film Museum included Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thom Andersen, and other subjects, but Henry Fonda for President, with the same exact title, was the name of a film series in that final season I did.

Preparing for it and reading up on him made me realize I could think of no other actor––this was in 2017, right at the beginning of the first Trump era––whose persona and life would allow me to describe certain essential conflicts of American democracy so well. I did not harbor other options. Now, I’ve been asked this question several times. I can certainly think of a few other actors, but I don’t want to answer in a way that suggests I’ll keep making films about actors. My usual answer is that Peter Lorre, who was born in 1904 in the Austro-Hungarian empire and would make a good case for the 20th century––including modernism, National Socialism, exile, and having to reinvent yourself several times over. His story goes through some of the essential moments of the century’s history. It could also become a film that’s not just a conventional biography. I’m sure there are others. I’m often asked if I see equivalents to Fonda in today’s actors and actresses. My first answer is that the cinema no longer plays the central role in the dream life. But maybe one could consider Denzel Washington…

Would you like to make a film about where the dream life has moved to?

I don’t even know if I want to continue my new profession. I spent five years making this film, and I’m happy with the positive response. But I don’t know yet where I would head next. To really be precise about today’s constellations between the “psycho-sphere” and the current political crisis, the cinema would not be the subject of such a film. A younger person would probably have to create something in a different media form. The forms of communication and visuality that dominate the current landscape are so different from what cinema contributed in the 20th century. I’m sure there can be great cinematic works about this situation, but I’m not the person to devise the best ways of making them. Arthur Jafa works between installations and films. He gives me great inspiration. I would have to start at zero to imagine the ways in which film, as a medium, would be able to approach this quagmire in Europe and North America.

Have you had any contact with the Fonda family?

In 2020, I learned that Peter Fonda was planning to visit the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, where I had been a regular guest. I immediately wrote to the director of the fest and asked if I could sit down with Fonda, not on record, but just to discuss his father. That summer, Peter Fonda became very ill and had to cancel his trip. His doctor forbade him from flying. At the end of the summer, he died. It was the last moment when I thought I could check my relation to the Fonda family. I had read Henry Fonda’s quasi-autobiography, Fonda : My Life / As Told to Howard Teichmann, and Peter Fonda’s and Jane Fonda’s memoirs at the start of this project. It was fascinating to read the three of them sometimes discussing the same event or topic. Second, I wrote to Jane Fonda, and I was in touch with her assistant. I didn’t directly need anything from her, but I wanted her to know I was making the film. Her assistant was very nice, but Fonda has not replied. Two months ago, I finally sent them a link. We’ll see if she has anything to say, but I haven’t been in dialogue with her.

Fonda speaks very frankly in the interview you excerpt. Do you think he was always that honest in the way he presented himself in public?

That entails a detailed discussion of what “honesty” means for a public persona. I don’t think he was ever this honest in his public appearances, but judging from the way he speaks about his attitude towards being a celebrity, he very carefully delineated those aspects of his personal life he wanted to be public and left out others. On the other hand, in this long interview, it becomes clear that his family told him he should leave a substantial record behind. He accepted two things: doing an autobiography, because he liked the collaborator, Howard Teichmann, and spending months telling everything to this man. And his family also convinced him that the Playboy interviews were worth doing. At the time it was a prestigious publication that would do 50-page interviews with intellectuals and politicians. It was a way to also promote his last film, On Golden Pond, which his daughter Jane produced and co-starred in. He said yes to Lawrence Grobel visiting him for a week and recording a total of 12.5 hours. He must have known anything he said could end up in the Playboy interview, and several of the more direct things did.

Nevertheless, the printed version is just a fragment of those 12 hours. I was very happy that Grobel let us access the complete audiotapes. I spent weeks and weeks transcribing them. I never met Fonda, of course, but I got a new feeling of the man, as much as I had researched him. The way he phrased certain things was more direct. I use a black-and-white clip of him on the BBC in 1959 when he speaks about his first meeting with John Ford. He says, “Ford said certain things you can’t say on TV,” but with Grobel, he gives us Ford’s profane language. I was surprised that he didn’t avoid the subject of his second wife’s suicide. He evaluates certain U.S. presidents and speaks directly about politics. At this point in his life he thought there was no need to hold anything back. I wouldn’t frame that under the rubric of honesty and dishonesty. He’s not very interested in backstage stories about filmmakers he worked with, but he spoke for an hour, in extremely detailed terms, about his three years in the Navy. He also seems to be more interested in speaking about organic farming.

How do you think the film was influenced by your previous work as a critic and curator?

My first answer to the question “do you want to make this film?” was, “Why me? Why should I?” If I convince myself it might be a worthwhile activity, it would definitely have to be in an area of filmmaking where I have something to contribute. My first entry into film was writing reviews and essays, then quickly I progressed into curatorial work. The knowledge related to those experiences was something I could count on. The essay-film tradition is something I have grown to value more and more. It became an incredibly important part of my cinephilia. As a young man I was strongly influenced by American, European, and Asian narrative films. Then I got interested in experimental works, then the strange and unique form of the essay film.

In 2007, the Austrian Film Museum and the Viennale did a large show together on the essay film. It was curated by Jean-Pierre Gorin and he called it “The Way of the Termite.” This five- or six-week show was such a pleasure for me, in helping to put it together and watching many of the films I hadn’t known before; that was the last straw in turning me into an aficionado of this form. Jean-Pierre really widened the field of what might be considered essayistic cinema. 10 or 12 years later, when I was suddenly in that situation, it was clear this project would be an essay film using my writing and voice.

My thinking has always been associative and non-linear. For a long time, I addressed questions in a serpentine manner, with side paths. This is served well by the potential of the essay film. I didn’t know it would become a three-hour film, but I knew it would be long and go into different directions, trying to catch marginal aspects of the main story. For me, they’re not so ephemeral. All of these things go back to my original experiences as a writer and curator. This goes for engaging with existing materials, whether they be TV shows or movies, with our own footage. So making this together with Michael and Regina also felt like a curatorial work––at least partly!

Henry Fonda for President opens at Anthology Film Archives on Thursday, April 3 and will expand.

The post Charting the Conflicts of American Democracy Through Henry Fonda’s Career first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Netflix’s ‘Devil May Cry’ Hits a Bloody Bullseye With Hellbeasts, Brutal Battles & Buffoonery [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Devil-May-Cry-Dante-With-Demons.jpg)

![‘Project Hail Mary,’ ‘Masters of the Universe,’ ‘After The Hunt’ Provide Amazon MGM Studios With Some Legit Fire [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/03034142/AmazonMGMStageCinemaCon.jpg)

![‘Wicked For Good’ & ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Look Massive For Universal Pictures [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/12165521/WickedSunset.jpg)

![‘Five Nights At Freddy’s 2’ Teaser Revealed & ‘How To Train Your Dragon 2’ Announced For 2027 [CinemaCon]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/02205821/Screenshot-2025-04-02-at-8.57.40-PM.jpg)