Coiba Island Penal Colony in El Trapiche, Panama

It was known as the Alcatraz of Panama. But unlike San Francisco’s infamous prison, the Coiba Island Penal Colony didn’t just have sharks off its shoreline to instill a fear of escape. Inmates also contended with scorching jungle temperatures, intense tropical storms, outdoor prison cells, and ferocious alligators roaming the island. These harsh factors not only encouraged redemption, they also kept human activity away from the island, creating a rich natural biosphere for when the prison reformed into a national park. From 1919 to 2004, the penal colony housed Panama’s most dangerous criminals and political opponents of the former military government. At its peak, 3,000 inmates lived in 30 open-air camps spread across the island. The remote island prison is also believed to be the site of the thousands of “The Disappeared” (or “Los Desaparecidos”) who vanished after arrests or kidnappings under the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s. It is speculated that many were fed to sharks or remain in unmarked graves near the former prison. The prison closed in 2004, more than a decade after Panama’s military rule ended with Manuel Noriega’s toppling in 1989. Panama’s democratically elected government then decided to preserve the biodiversity of Coiba Island—and its surrounding 38 smaller islands—by designating it a national park. Coiba National Park (Nacional Parque Coiba) now covers 430,825 acres and its surrounding waters. Panamanians long feared the island because of its tortuous reputation. This lack of human interaction—and its remote location—led to the Americas’ largest undeveloped rain forests, with 80 percent of the jungle untouched. In 2005, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site and declared a Special Zone of Marine Protection. The tropical forest is booming with wildlife, like the Coiba Agoutis, as well as Panama’s largest scarlet macaw population, and the country’s only brown-and-white spine-tail birds. Coiba also hosts a population of crested eagles and numerous reptiles like alligators, giant toads, and green iguanas. Its white sand beaches and shoreline are also inhabited by hawksbill sea turtles. The island features plunging waterfalls and hot springs surrounded by clear waters of untouched protective coral reef—one of the largest in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Its waters are home to nearly 1,000 fish species and dozens of shark species. Prison structures—outdoor cells, a former chapel, and armory buildings—are slowly being overtaken by jungle foliage and erosion. Some significant structures, like the chapel, are being preserved. A small military outpost in the former prison administration buildings keep watch over the island’s tourists and any drug traffickers trying to use these waters. Sometimes, the old cells temporarily hold traffickers awaiting mainland prosecution.

It was known as the Alcatraz of Panama. But unlike San Francisco’s infamous prison, the Coiba Island Penal Colony didn’t just have sharks off its shoreline to instill a fear of escape. Inmates also contended with scorching jungle temperatures, intense tropical storms, outdoor prison cells, and ferocious alligators roaming the island. These harsh factors not only encouraged redemption, they also kept human activity away from the island, creating a rich natural biosphere for when the prison reformed into a national park.

From 1919 to 2004, the penal colony housed Panama’s most dangerous criminals and political opponents of the former military government. At its peak, 3,000 inmates lived in 30 open-air camps spread across the island. The remote island prison is also believed to be the site of the thousands of “The Disappeared” (or “Los Desaparecidos”) who vanished after arrests or kidnappings under the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s. It is speculated that many were fed to sharks or remain in unmarked graves near the former prison.

The prison closed in 2004, more than a decade after Panama’s military rule ended with Manuel Noriega’s toppling in 1989. Panama’s democratically elected government then decided to preserve the biodiversity of Coiba Island—and its surrounding 38 smaller islands—by designating it a national park. Coiba National Park (Nacional Parque Coiba) now covers 430,825 acres and its surrounding waters.

Panamanians long feared the island because of its tortuous reputation. This lack of human interaction—and its remote location—led to the Americas’ largest undeveloped rain forests, with 80 percent of the jungle untouched. In 2005, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site and declared a Special Zone of Marine Protection.

The tropical forest is booming with wildlife, like the Coiba Agoutis, as well as Panama’s largest scarlet macaw population, and the country’s only brown-and-white spine-tail birds. Coiba also hosts a population of crested eagles and numerous reptiles like alligators, giant toads, and green iguanas. Its white sand beaches and shoreline are also inhabited by hawksbill sea turtles.

The island features plunging waterfalls and hot springs surrounded by clear waters of untouched protective coral reef—one of the largest in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Its waters are home to nearly 1,000 fish species and dozens of shark species.

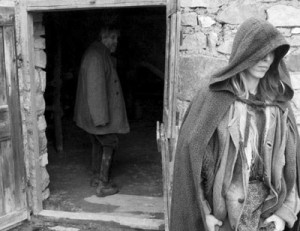

Prison structures—outdoor cells, a former chapel, and armory buildings—are slowly being overtaken by jungle foliage and erosion. Some significant structures, like the chapel, are being preserved.

A small military outpost in the former prison administration buildings keep watch over the island’s tourists and any drug traffickers trying to use these waters. Sometimes, the old cells temporarily hold traffickers awaiting mainland prosecution.

![Leaked: Elon Musk’s Jet Playbook—65°, Dim Lights, No Vents—And Full Throttle, Always [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/20170726_084344.jpg?#)

![‘I’ve Got 8 Chickens at Home Counting on Me’—Delta Pilot Calms Nervous Cabin With Bizarre Safety Promise [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-cabin.jpg?#)