An Arrest in Brazil Highlights Country Music’s Deep Struggles With Streaming Fraud

Sertanejo artist Alex Ronaldo created a stream farm as a side hustle, but "everything is bought and paid for here," says one music manager.

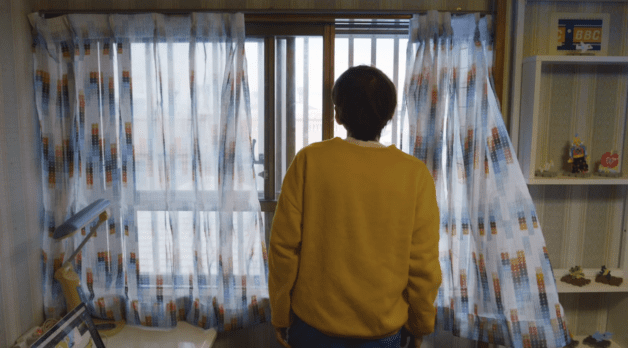

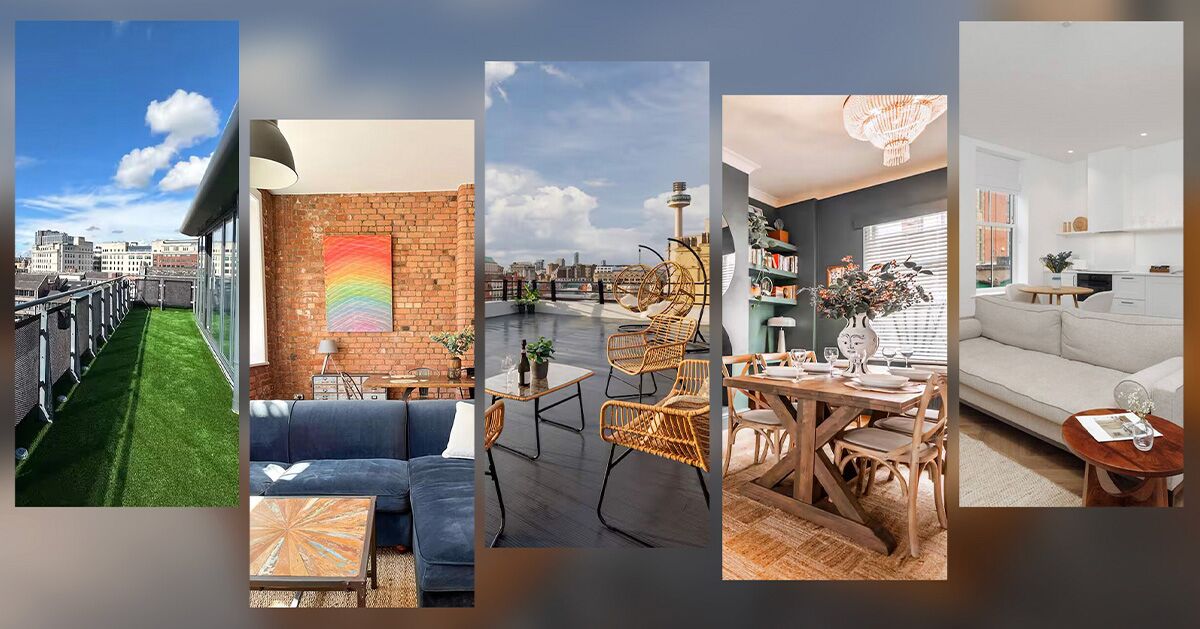

GOIÂNIA, Brazil — As the global pandemic deepened, Brazilian country artist Alex Ronaldo watched his career ebb away. So the veteran music writer cooked up a side hustle: He took hundreds of demos he regularly received from aspiring artists — mostly in the sertanejo, or Brazilian country, genre — and put them out on Spotify under false names and fake artists, with fake cover art, all created from his luxury seafront condo.

In December, three years after he launched his illegal money-making scheme, prosecutors arrested and charged Ronaldo Torres de Souza, who performs under the moniker Alex Ronaldo, in the first prosecution of an individual in Brazil for streaming fraud. The sertanejo artist confessed to uploading more than 400 tracks by other artists under false names to Spotify that generated more than 28 million fake plays — using artificial intelligence to aid in the scheme.

The major labels, via Brazil’s recorded music association Pro-Música Brasil, along with Brazil’s anti-piracy body Association for the Protection of Phonographic Intellectual Rights (APDIF), cooperated on what they are calling Operation Out of Tune. “Simply put, streaming manipulation of this nature is theft — stealing directly from artists and betraying fans,” Victoria Oakley, the CEO of IFPI in London, said in a statement last week.

As seemingly important as his arrest was, in Goiânia — the “Nashville of Brazil” — the case underscored to music executives how little was being done to tackle a more serious problem plaguing the Brazilian industry: the buying of fake streams by artists, managers and music label executives to prop up artists on Spotify’s charts.

Brazilian music executives said a furious scramble for Spotify chart dominance is spurring artists to spend tens of thousands of dollars on fake plays for individual songs — and Spotify is doing little that they can see to stop it.

“Everything is bought and paid for here,” Gláucio Toledo, a sertanejo music manager, said about music streaming success in Brazil. “I know three people who got rich selling fake playlists. It has become an unfair competition in the digital world.”

Other industry observers are hearing similar concerns. “Brazil is on a lot of people’s minds across the industry, big and small,” says Morgan Hayduk, the co-CEO and co-founder of Beatdapp, a Vancouver-based company that specializes in streaming fraud detection. “When we talk to rights holders or to platforms there are questions about what they see in their Brazil data.”

One top music manager told Billboard that so-called stream brokers peddle 1 million streams for 50,000 reais ($8,750). That level of spending outpaces the average of around $4,000 that Spotify pays out for a million streams, this person said. The typical fraud scheme involves accessing fake-stream farms in Brazil or outside the country that use dozens if not hundreds of laptops and cell phones to run Spotify accounts continuously.

Spotify says it “invests heavily in automated and manual reviews” to prevent, detect and mitigate artificial streams on its platform. “When we identify stream manipulation, we take action that includes removing streaming numbers and withholding royalties,” a Spotify spokesperson said. “Bad actors are always evolving, so our dedicated fraud prevention team is always working to identify new trends and methods used to game the system.”

Nevertheless, competition to out-buy other sertanejo artists “is hindering other genres, such as funk, pop, MPB and electronic music, which sometimes struggle to make it into the top 10 or 15 because [the lists] are inflated,” says Raphael Ribeiro, CEO of AudioMix Digital, the Goiânia-based label and artist management company that launched several big sertanejo artists, including Gusttavo Lima, Jorge & Mateus and Wesley Safadão.

Fraud is also limiting the barriers to entry for less wealthy artists in Brazil. “Nowadays, it’s hard for an artist to break through if you don’t get involved in a scheme, if you don’t pay for streams, if you don’t create a bot, because there’s a lot of money involved,” Ribeiro says.

Heavy stream-buying could at least partly explain sertanejo’s dominance in Brazil over the past several years. Seven of the top 10 most-played tracks on streaming platforms last year were sertanejo, according to Pro-Música, with Felipe & Rodrigo’s live version of “Gosta de Rua” grabbing the top spot.

In Brazil, streaming success on Spotify strongly impacts touring and sponsorship fees for artists. Top concert earners include Jorge & Mateus and Lima, the latter of whom is so popular that until two weeks ago he was publicly weighing a run for president of the country next year. (He said he would focus instead on conquering the Spanish-language Latino music market.) Reaching the top 50 on Spotify typically boosts an artist’s touring fee to at least 300,000 reais (about $52,000), two Brazilian music managers said.

Brazil’s overall recorded music market is among the fastest growing in the world. Last year it grew 21.7% to 3.49 billion reais ($609 million) to land in ninth place on IFPI’s global ranking (88% of revenues came from on-demand streams), despite the country’s currency remaining historically weak compared to the U.S. dollar. That’s up more than double from the $296.2 million and 12th place it held in 2020, according to IFPI’s annual Global Music Report.

Allegations of an underground market in Brazil for buying and selling fake streams to prop up artists first began to spread during the pandemic, when a senior manager at a streaming platform and one executive at a major label — both based in Brazil then — told Billboard that stream-buying by big-name artists was prevalent, especially in sertanejo — and that indie and major labels were involved.

Fraudsters have had a head start on Brazilian investigators. The public prosecutor’s office in the state of Goias, where Goiânia is located, only organized a cybercrime unit last year. And prosecutors acknowledged that the Torres de Souza probe, which involved authorities in two other states, piggy-backed on reporting by Brazilian news site UOL — largely because none of the more than 50 composers who were victimized reached out to authorities first, they said.

Still, Brazil has done more than most countries.

Previous law enforcement efforts have focused on shutting down websites peddling fake streams and stream-ripping services, rather than on rooting out individual fraudsters. Pro-Música president Paulo Rosa told Billboard in 2022 that most of the illicit activity affecting Brazil was being conducted outside the country by mirror sites in Russia. Last year, Operation 404, a global anti-piracy effort, dismantled the top three most popular stream-ripping mobile apps in Brazil, while another initiative, Operation Redirect, targeted illegal music sites in Brazil associated with malware distribution.

“There have been very few streaming cases channeled through proper authorities anywhere around the world,” Hayduk says. “To see three in Brazil is still a meaningful number.”

Homegrown Streaming Fraud

That said, Torres de Souza’s case showed that a relatively uncomplicated streaming fraud operation can go undetected for years. At his apartment in Recife, in the northeast of the country, the artist, who has 13,000 monthly listeners on Spotify, used fake documents and emails to register other artists’ demos with distributors. Then he published the songs on Spotify and social media platforms under fake names and fake artists, using AI-generated fake cover art.

The heart of the scheme involved setting up 21 computers that ran the open-source program Sandboxie on various internet browsers, which could generate up to 16 virtual computers on each machine. That meant he could have up to 2,000 browser windows open simultaneously pumping out mostly Spotify streams for the music he illicitly appropriated, prosecutors described in their 90-page complaint.

Investigators seized computers and hard drives containing thousands of demos and hundreds of pieces of cover art. Torres de Souza ran the computers 24 hours a day, only disconnecting them when he traveled to avoid starting a fire, Fabrício Lamas, a prosecutor with Goiânia’s cybercrime unit, CyberGaeco, tells Billboard.

In the first year or so, the sertanejo artist relied on demos from aspiring artists to generate his illicit income. Then in the past year, he turned to fast-evolving AI programs to also create fake music, prosecutors said.

By all accounts, Torres de Souza, 47, was acting alone in the scheme. His wife of more than a decade was oblivious to what he was doing with a wall full of laptops running Spotify accounts all day long, according to prosecutors.

The scheme wasn’t always that sophisticated. The sertanejo artist ascribed fake male artist names to some songs that had female singers. And some AI-created cover art didn’t even refer to actual songs. Fake artist “Regis Costa,” for example, had cover art for “Taça de Vinho” (Wine Glass) — with an image of a martini glass instead of a wine glass — but there was no such song on the album.

Prosecutors estimated Torres de Souza generated more than 300,000 reais ($52,000) in illicit royalties from the first 400 or so songs identified. They expect that number to grow significantly when they gain access to his bank account in a few months, as proscribed under Brazilian banking law.

Torres de Souza faces a potential prison sentence of more than 10 years for the fraud scheme, Lamas said. Prosecutors and his attorney José Paulo Schneider said the music artist cooperated fully in their probe and expressed remorse for his actions. He was released from jail and is awaiting trial.

“This operation, when they got to Alex Ronaldo, was just the tip of the iceberg, but [investigators] didn’t look at the bigger picture,” Schneider says. “There are many artists who use this kind of non-organic reproduction to be able to make their songs go viral — in short, to monetize them.”

Blame Game

The length of Torres de Souza’s potential sentence could come down to who claims they were a victim, which is not so clear, Lamas says.

“There is a lot of confusion,” the prosecutor says. “The composers’ associations, the record companies’ associations and the streaming companies say, ‘We are not victims.’ But who is paying? The streaming companies, who say, ‘We don’t pay them, we pay the distributor’? It’s kind of a blame game.”

Goiânia prosecutors criticized Spotify, saying the company chose not to collaborate. “In this specific case, there was no delivery of platform information,” says prosecutor Gabriella de Queiroz Clementino. “Spotify stated that it had no interest in the criminal investigation.”

A Spotify spokesperson denied that charge. The platform “cooperated fully with the authorities to provide all requested information and certainly did provide an explanation about its processes to detect and mitigate artificial streams,” the spokesperson said, noting that Spotify “continues to be collaborative during this investigation.”

Lamas says prosecutors “are aware of other situations” involving steaming manipulation but would not provide further detail. “For us to effectively combat this, the state needs better collaboration from the companies that receive this data,” he adds.

For music industry officials who see stream-buying happening in Brazilian country music with impunity, new fraud probes couldn’t come soon enough.

“To me, the greatest harm from this [fraudulent stream] activity is that it generates a lack of credibility in the market,” says Marcelo Castello Branco, president of the Brazilian Union of Composers (UBC). “There will come a time when even the consumer will not believe these numbers.”

Alexei Barrionuevo is Billboard’s former International Editor.

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)