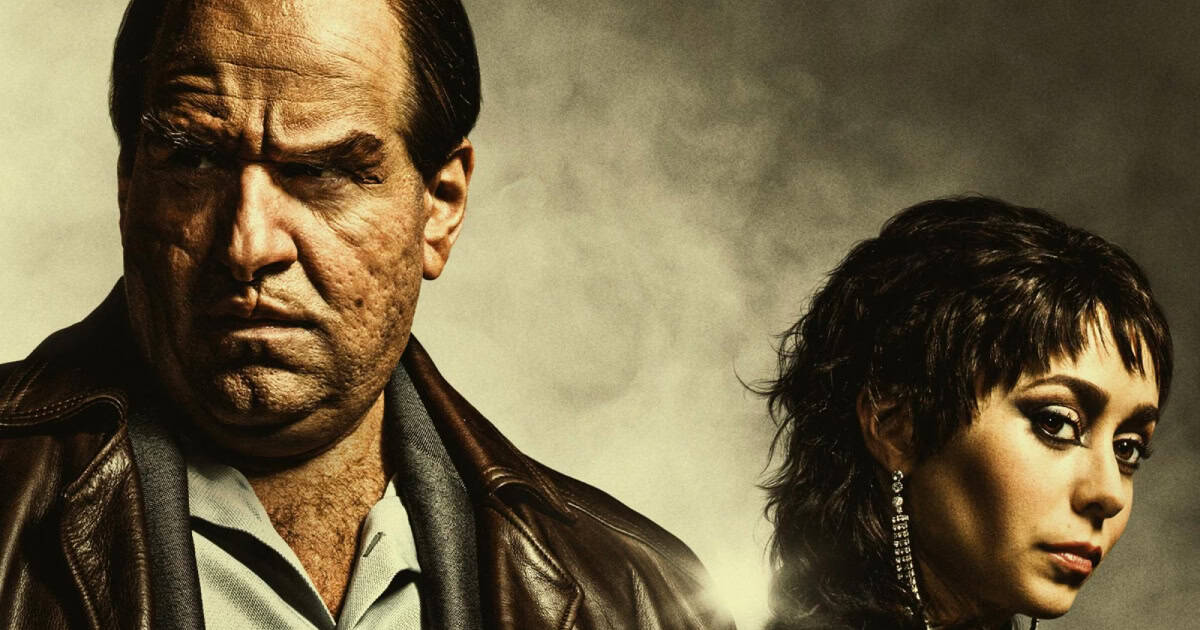

Sinners Review: Ryan Coogler Breathes Life Into Richly Told, Carnal Vampire Tale

From increasingly overbearing Eat the Rich satires to a never-ending, post-Get Out wave of social commentary-infused horror, it seems like there’s no end in sight to what the New Yorker recently dubbed cinema’s “plague of literalism.” For genre movies in particular, each satirical target is laid on as thick as the gallons of blood splatter––impossible […] The post Sinners Review: Ryan Coogler Breathes Life Into Richly Told, Carnal Vampire Tale first appeared on The Film Stage.

From increasingly overbearing Eat the Rich satires to a never-ending, post-Get Out wave of social commentary-infused horror, it seems like there’s no end in sight to what the New Yorker recently dubbed cinema’s “plague of literalism.” For genre movies in particular, each satirical target is laid on as thick as the gallons of blood splatter––impossible to misinterpret or get lost beneath the gore, a factor which makes them less interesting to unpack despite the way filmmakers put their ambitious allegories front and center. It may result in immediate critical acclaim––as was the case with The Substance––but no director’s idea can continue to linger in the consciousness when it’s dispensed so plainly, no additional food for thought beyond what meets the eye.

My fear was that Sinners, director Ryan Coogler’s return to original filmmaking after two great franchise films––and one disappointing, disjointed sequel––would follow a similar path. In this literal era, you don’t get a major studio to bankroll an expensive, non-IP project if there’s the chance its ideas won’t universally resonate. Somehow, despite a splatter-friendly premise riffing on From Dusk Til Dawn, Coogler has been afforded the space to treat his audience like adults, refusing to draw overt parallels between his period tale and the modern day, letting his film play like a well-executed thrill ride at surface level, while a far richer text without a single allegorical interpretation when inspected at greater depth. It’s less like Get Out than the films Jordan Peele made after ascending to Blank Check filmmaker status; I won’t be surprised if the first wave of critical reactions are similar to those which greeted Us, aiming to interpret the film as chasing a singular metaphor when it’s a messier beast with far more on its mind.

Coogler and Peele are very different filmmakers, and the comparison between the two isn’t solely because they’re two of the few Black directors now provided the chance to helm projects on this scale. It’s because I see Sinners as likely to fall prey to the same misinterpretation as Get Out via liberal critics who initially viewed it as a skewering of Trump-era American society while it analyzes underlying social structures that long predated both of his stints in the White House. That temptation to utter his name will be felt by many in the opening five minutes as twin brothers Smoke and Stack (Michael B. Jordan) are touring a disused warehouse they hope to renovate and reopen as a juke joint; it’s 1932 and they’ve just returned from Chicago to their hometown in Jim Crow-era Mississippi, but the white landlord showing them around their new place of business assures them the KKK and other racial hatred is a thing of the past. If you already know that Sinners is a supernatural shocker going in, you might be cynically inclined to assume this is the lay-up for an obvious horror metaphor about the racism we see on a daily basis nearly a century later. It isn’t.

Coogler refrains from any simplistic mirroring between this post-Depression era and our own, spending the first half of his tale patiently building a character drama about two brothers returning home after several years and using the money they earned from their jobs in Chicago––rumors swirl that they were under the wing of Al Capone––to buy their way back into relationships they put on pause. As with From Dusk Til Dawn, which the writer-director has named one of his biggest influences, the first half is divorced from horror almost entirely, richly fleshing out the brothers and their acquaintances as they rush to throw an opening party at their juke mere hours after buying it. It’s rare to see a big studio film where the director has been given freedom to fully realize his period setting at the expense of the plot, often letting his film breathe so musician characters (played by the extraordinary newcomer Miles Catton, as the twins’ cousin, and the ever-brilliant Delroy Lindo) can perform, stopping the track of time all around them.

In the case of Catton’s Sammie Moore, a young blues prodigy, that skill is made literal. Few directors have deployed the IMAX camera as well as Coogler does for a oner in which centuries of Black music (from blues and jazz to contemporary hip hop) converge in a shared space through the power of his performance, the only time the film gestures past its period setting. It’s a simple testament to the power of music that will sound limp when described on paper but is utterly breathtaking in action. In terms of allegory, music is the driving force––especially when a vampire army led by Jack O’Connell’s sinister folk singer Rennick strolls outside, desperate to be let in. Coogler doesn’t aim to subvert vampire lore, with the same rules and mythology as any other story in this genre, but what the monsters represent is far less clear-cut.

Two of Rennick’s first victims are KKK members, but I saw this as a purposeful misdirect, letting the viewer assume racism is the straightforward motivator for their superior’s actions when he’s a stand-in for a more structural evil: the exploitation of Black artists and appropriation of Black culture by white audiences who will lovingly consume their creations whilst acting against their best interests in life. There are brief lines of dialogue making this literal, but it’s far less heavy-handed than it reads––that many will stamp a simplistic MAGA-critiquing allegory onto the third act, rather than a bolder middle finger at underlying social structures, will only reaffirm this. In actuality there’s a far greater complexity, and the arc of Stack’s white-passing girlfriend Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) will likely trigger divergent debate on whether Coogler pulls this off.

Yet Sinners mainly feels so refreshing when this richness of text can easily be overlooked for enjoyment of an unholy hybrid of period drama and horror freakout, Coogler showing as much reverence for the genre as he does the centuries of music which guide this story (and Ludwig Göransson’s excellent score). Most importantly, he remembers that the archetypal vampire tale is an inherently horny one, and he pulls some tricks from Luca Guadagnino’s book for making sexually explicit stories which play even more erotically from what they withhold. Every sex scene features fully clothed actors, but all contain dialogue, or specific kinky details, which serve to remind us that, Dracula onwards, the best vampire stories are carnal ones where characters’ lust is baked into the premise.

Coogler doesn’t reinvent the vampire movie with Sinners, but in a current era of American cinema where messages are force-fed, a thoughtful social satire which gives viewers time to dissect––and never lets its loftier thematic aims get in the way of its junky thrills––is a breath of fresh air. I can’t remember the last time I had this much fun, nor felt so reinvigorated by, a major studio genre movie.

Sinners opens in theaters on April 18.

The post Sinners Review: Ryan Coogler Breathes Life Into Richly Told, Carnal Vampire Tale first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Leaked: Elon Musk’s Jet Playbook—65°, Dim Lights, No Vents—And Full Throttle, Always [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/20170726_084344.jpg?#)

![‘I’ve Got 8 Chickens at Home Counting on Me’—Delta Pilot Calms Nervous Cabin With Bizarre Safety Promise [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-cabin.jpg?#)