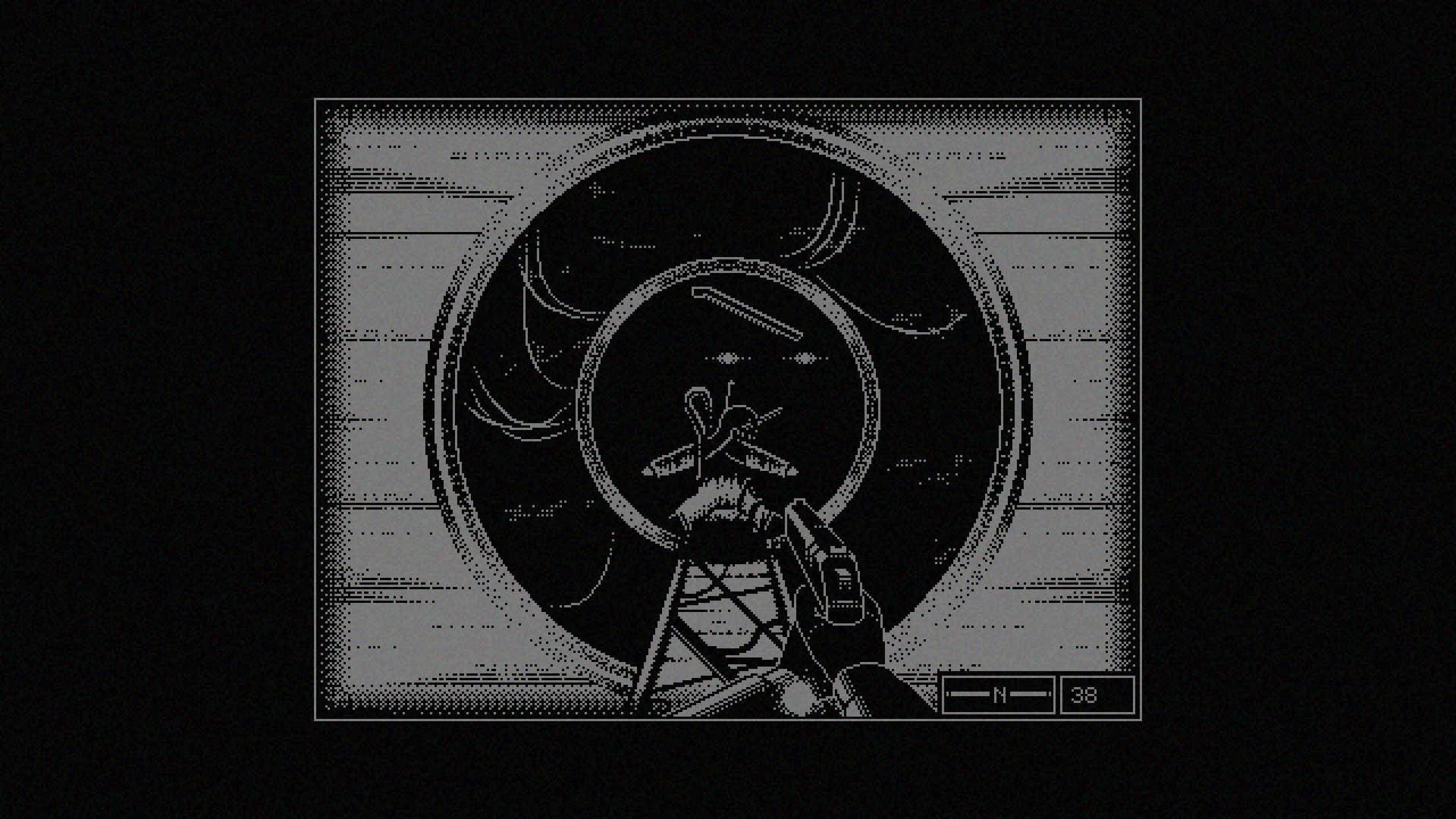

Short Films in Focus: Incident

A dive into the Oscar-nominated short, as well as the virtues and limitations of found footage.

I find it challenging to review “found footage” documentaries where the primary focus is on the footage itself. You watch it. It makes sense that someone would release the footage into the world. You make sense of it in the context of our world today. And you think, “Wow. Nothing’s changed in our world,” or something like that. And you move on. Then again, you may remember that one such movie, “A Night at the Garden,” got an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Short for doing just that. In that case, the footage was of a Nazi rally that seemed eerily similar to rallies that had taken place in 2016. No commentary, no parallel footage or anything. Just the footage itself, edited with some background music thrown in. Instant Academy Award nomination.

Fast forward a few years and we have Bill Morrison’s “Incident,” another Academy Award-nominated found footage documentary where the footage speaks for itself, but this time, there appears to be more skill and more of an urgency to it. When it ends, you have more of a feeling of helplessness and anger than one of just stumbling upon an interesting discovery.

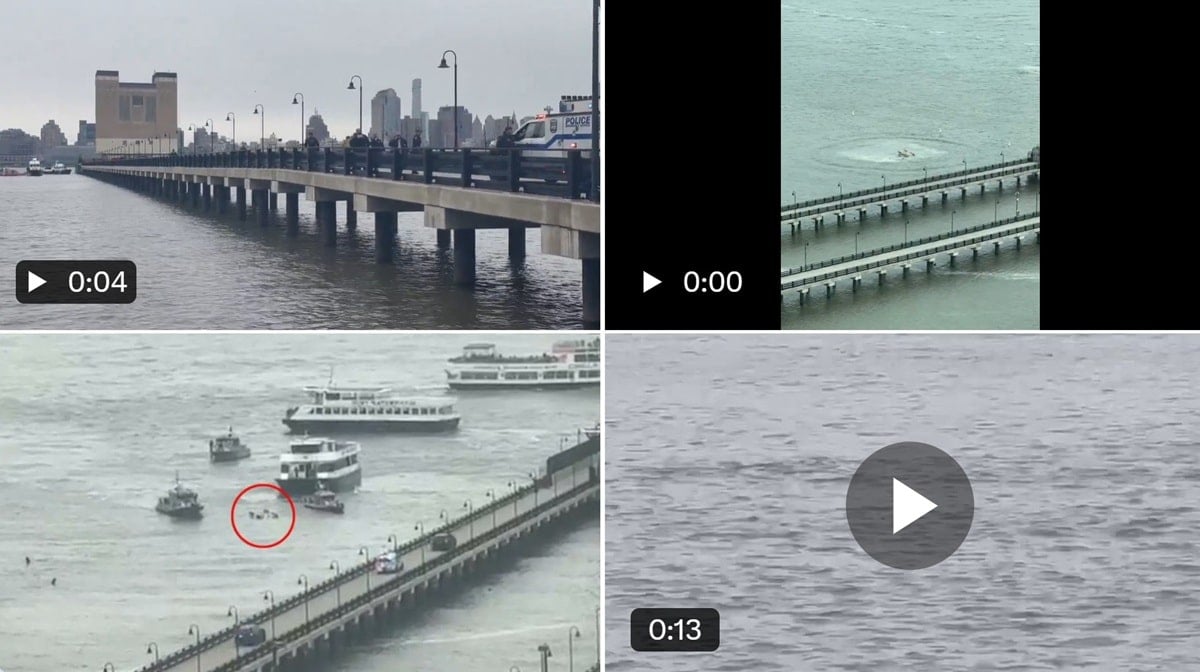

The incident in question took place on July 14th, 2018, at 5:30 pm at East 71st Street in Chicago, a couple months before the trial of the murder of Laquan McDonald. Police presence in this neighborhood has increased, further escalating the tension between law enforcement and the citizens. Through surveillance footage, we see a group of officers standing around. One of them sees a Black man approaching. They believe he may be armed. Their paranoia increases, and they question him. One officer thinks the man is taking out a gun, and the police respond swiftly, killing the man right there in the street. Turns out he never took the gun out. He carried it legally and worked as a barber, Harith “Snoop” Augustus, a well-known fixture in the neighborhood. The police officers work to cover it up and get their stories straight until the ambulance arrives. Many citizens witnessed the incident.

There is more that occurs in the aftermath of the shooting that I will leave for you to discover. Morrison utilizes several perspectives of surveillance and body-cam footage as more officers arrive on the scene and make discoveries about what happened, while neighbors express outrage over yet another innocent man gunned down by trigger-happy officers. The film spans approximately twenty minutes of uninterrupted time, utilizing a flashback and flash-forward structure at the beginning and end to provide further clarity to the viewer, with as many as four different perspectives visible at once.

Perhaps a less accomplished filmmaker than Morrison, who has made several films centered on found footage, would have felt the need to incorporate music into the tragic events to help underscore the obvious. He instead makes the bold choice to go completely silent for the first few minutes of the film as we read what we need to know before the events unfold. Morrison then skillfully lets the audio from the different cameras tell the essential aspects of the story, providing subtitles in each frame, making everything that much easier to follow. This is not just a presentation of found footage; it’s a thorough and investigative piece of reporting that should be more common in the media landscape but seems seldom practiced.

One of the more curious and damning parts is a piece of audio, in which an operator asks: “Did you tell every officer on the scene to turn off their body cameras?” Apparently not. The body cameras, we are told, exist now because of the Laquan McDonald shooting, because of incidents like this. Had they all turned off their cameras, perhaps Morrison wouldn’t have as much of a movie here. It is also very telling that the officers continue to guard and correct their speech, knowing full well that everything they say is being recorded and can, per the law, be released to the public 60 days after an incident. They appear to be trying to craft some convincing performances for their superiors to see.

Obviously, no one involved that day could have guessed that their behavior and conspiracy would be the subject of an Academy Award-nominated film that thousands would watch (especially back in February) in the documentary shorts program. Still, it’s now etched in stone for all to see. In real time, we see the shooting, the cover-up, the neighborhood outrage, and the confusion of the officers who arrive later on to figure out what happened. They didn’t have the advantage of looking at the body-cam footage at that moment, but we have it now. Because of Morrison’s skill as an editor and investigator, we have an all-too-familiar story laid out before us that the viewer won’t soon forget. On the other hand, police officers who see this will think more critically about their own body cam footage and might consider turning it off at the wrong time. That would be a different kind of tragic mistake.

![‘Until Dawn’ Director David F. Sandberg Breaks Down the Film’s Practical Effects [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/untildawn-worm.jpg)

![The 5 Biggest Takeaways from “The Last of Us” Season 2 Premiere [Spoilers]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/kaitlyn-dever.jpg)

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Bright Spots in the Darkness [My 1998 Top Ten List]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/rochefort.jpg)

![Bad Ideas [on WILD AT HEART]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/wildatheart2.jpg)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)