Let the Circle Be Broken: Sister Sadie’s New Song Shows Country Women Reclaiming the Narrative

Country women are done being the silent muse — and the industry is finally listening.

Fiddler Deanie Richardson was about to go onstage for a sound check at the Grand Ole Opry in 2023 when she got word that her father had died.

He had abused Richardson verbally, physically and — during her teens — sexually. She had longed for his passing for years, but now that the moment had come, she experienced a complicated mix of emotions. She was sad to have never had the kind of supportive dad that she deserved. But she simultaneously sensed something new and hopeful.

“It felt like all the chains [were broken],” says Richardson, a founding member of all-female bluegrass group Sister Sadie. “I felt like a prisoner to him my whole life. But that moment, I felt free, and for the first time in my life, I got onstage and I felt like I was playing for me.”

Her father had been abused by his father, and when he got Richardson’s mother pregnant at age 16, he resented the marriage and the child. He dealt with his anger in the same way he had learned from his father, doling out severe levels of abuse to the family.

After his death, Richardson, Erin Enderlin and Sister Sadie lead singer Dani Flowers co-wrote “Let the Circle Be Broken,” bending the title of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” a country standard that has been shared through multiple generations. They wrote it in a way that was “less about what I experienced and more about how I chose to stop it,” Richardson says. “It can die right here.”

Sister Sadie released the song on April 4. It captures Richardson taking control over her life and demanding to tell her story, which she believes can help other females in similar situations. But it also parallels the way that women in country have evolved creatively.

“I think Deanie’s story can be a powerful metaphor for what is happening with women in country music,” says Middle Tennessee State University College of Media and Entertainment dean Beverly Keel, a co-founder of Change the Conversation, a Nashville organization that supports women in the music business. “They are reclaiming the narrative and sharing things from their perspective.”

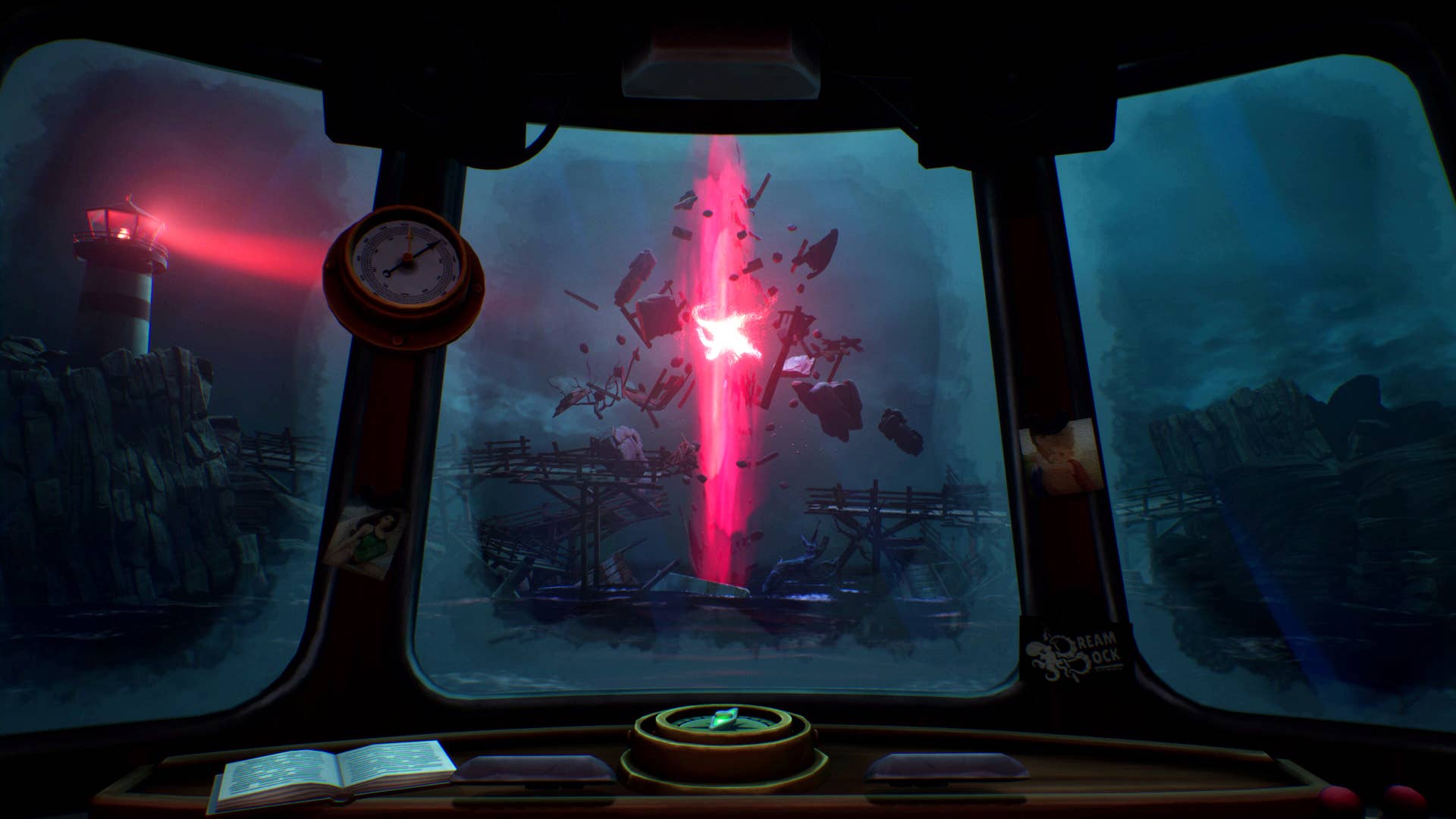

Murder Ballads: Illustrated Lyrics & Lore (April 29, Andrews McMeel/Simon & Schuster), authored by Katy Horan, documents some of the most horrific male aggression toward women. It compiles the histories of numerous early folk and country songs about stabbings and drownings, including songs in which men kill women, usually to hide an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. The perpetrators prioritize their reputations in the community over the life of their girlfriends, who would have been viewed more like an accessory than an equal partner in that era.

“These songs were used to force women to control their behavior,” Horan notes, “but they never hold men accountable.”

Caroline Jones‘ first BMLG release — “No Tellin’,” out March 28 — finds her mining an abusive relationship from her youth, demonstrating how bringing oppression out of the shadows can deflate its power.

“The shame and the manipulation around secrets is the way that people are able to stay in abusive situations,” Jones notes. “The song is about the freedom of telling the truth, because as long as something is a secret, there’s no oxygen around it, and the only story that you know is the one that you’ve been told. Once you tell the story to other people, you can get a different truth from people that truly love you.”

Richardson carried the secret that inspired “Let the Circle Be Broken” for years as she became a prominent Nashville musician. She toured with the likes of Patty Loveless, Bob Seger and Vince Gill, and regularly plays fiddle during the Country Music Hall of Fame inductions as a member of the Medallion All-Star Band. Sister Sadie became the first all-female ensemble to win the International Bluegrass Musicians Association’s entertainer of the year award. Richardson, after first playing the Opry at age 13, became a regular member of the show’s band. Her father inevitably haunted those performances.

“I knew every night he was listening, and I knew I was going to get the same reaction on the way home from the Opry,” she recalls. “I would call him and I would just ask if he had been listening, hoping to get some sort of encouragement, hoping that one day he’s going to say, ‘Wow, you really killed it tonight.’ But it was always some sort of little jab, you know — it was always ‘not good enough’ or ‘never going to measure up.’ But I was always trying, at least before he died, to get that one moment where he said, ‘Wow, you’re really fucking good.’ “

Abuse, she would discover, has affected a number of people that she knows, but was allowed to flourish in silence.

Hiding the violence, as they did in her house, mirrors the way society treated it until the late 1800s, when laws were first enacted in some states that made domestic assault a crime. Though discussed rarely in everyday conversations, the subject found its way into murder ballads such as “Ommie Wise,” “Delia’s Gone” or “Knoxville Girl,” covered by The Louvin Brothers in 1956.

“They’re so damn chipper when they’re singing that song,” Horan says. “It’s so weird.”

Subscribe to Billboard Country Update, the industry’s must-have source for news, charts, analysis and features. Sign up for free delivery every week.

The women in the murder ballads were almost uniformly desirable, and they were pitied in their deaths, but also blamed for them. By killing them, the murderers were able to gain full control since the dead women could no longer act of their own accord.

“The dead white woman is almost like this image of perfection,” Horan says. “She has no agency. She cannot transgress any rules. She is perfect in her stillness.”

The threat of violence is one of the methods that abusers use to control others. Richardson witnessed that in her father.

“He controlled how I wore my hair, the clothes I wore, who I talked to at school every single day,” she remembers. “As a teenager, my stomach was just in knots knowing at 3:30 he was going to walk through that door and I was going to have to endure all these questions: ‘Who’d you talk to today?’ ‘Who’d you sit with at lunch?’ ‘Did you talk to any boys?’ There was anxiety every single day, just living with him.”

She knew the penalties if she didn’t please him.

“He would crush my fingers if I didn’t play the way he wanted me to play,” she says. “He was just very, very abusive on all fronts.”

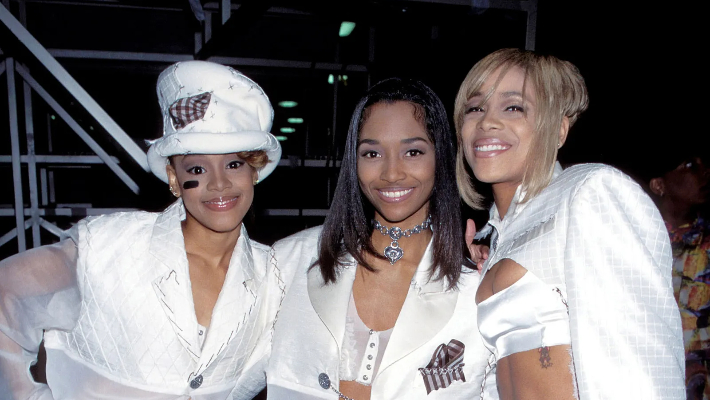

Several generations of women have retaliated against that kind of abuse, though progress is typically gradual. That was particularly true in country music. Kitty Wells was the first female to earn a No. 1 single in 1952 with “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” an “answer song” to Hank Thompson‘s “The Wild Side of Life,” which blamed a man’s heartbreak on female philandering.

Women were, for years, widely referred to condescendingly in country as “girl singers.” Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Faith Hill, Shania Twain, Martina McBride, The Chicks and Carrie Underwood were among those whose music supported females claiming their independence, in some cases taking revenge for domestic violence.

During the bro-country era in the last decade, women were often reduced to sexual objects, and their voices were mostly silenced as airplay waned for many females. Those who broke through — particularly Underwood, Miranda Lambert and Kacey Musgraves — embraced empowerment themes.

By building on the strength of the women who preceded them, country females in 2025 continue to push the boundaries. A trio of current songs — Ella Langley‘s “you look like you love me” (a collaboration with Riley Green), Dasha‘s “Not at This Party” and Chappell Roan‘s “The Giver” — feature women in frank discussions about their most private moments. Instead of repressing their personalities, as they would have likely been forced to do in previous generations, they are operating in control of their own stories and their relationships.

“They’re owning all the aspects of their life: their needs, their desires, their hurts, their pains, their dreams, and they’re not ashamed by any of it,” Keel says. “Shame and blame have been so strong in so many women’s lives.”

These songs would have likely been poorly received in previous eras. But instead of being shunned, Langley is the Academy of Country Music’s top nominee and Roan earned a No. 1 single on Hot Country Songs. Dasha, an ACM nominee for new female vocalist of the year, is insistent that women should fight for their full expression.

“No one else is going to do it,” Dasha says.

The current generation of country women is addressing difficult topics more readily than ever, pushing the envelope in their frankness about relationships, but also increasingly pulling the curtain back on the family secrets.

“A lot of these things are being addressed as never before, so I think it makes for a much more open conversation,” Jones says. “And I feel very lucky to be living in a time when that’s possible, because we’re going to help a lot of people.”

Women may need to fight to maintain that possibility. Recent national developments — from the Supreme Court’s rulings on abortion to the dismissal of several women in leadership roles — have reduced the gender’s autonomy and influence.

“We’ve got the federal government erasing the history, experiences and accomplishments of women on their websites and in their language,” Keel says. “Female military leaders are getting fired, so we need to hear about the entire female experience.”

Richardson personifies country females’ creative development. After hiding the misery of her family’s abuse for most of her life, she has publicly shared her story in “Let the Circle Be Broken,” conquering her father’s domination each time Sister Sadie plays it.

“When we do this song every night, it’s coming out of my fiddle, which is so ironic and so therapeutic because the fiddle was a thing that he tried to control,” she says. “And now I’m up there playing this song about him, and every night we do this improv thing at the end of it where I just play as long as I want to play. Some nights I just cry and play. And some nights I play for five minutes. It just depends on what I need.”

Just as Richardson has claimed the freedom to tell her story in recent years, the women of country have fought for the same privilege.

“We’ve gone from women being impregnated and killed, and everything blamed on them, to women singing about, ‘Hey, I’m going to rock your world tonight,’ ” Richardson says. “That feels very empowering to me.”

![How That Shocking Death in the “Daredevil: Born Again” Season Finale Came Together [Spoilers]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/OTK-109-59461_R-scaled.jpg?fit=2560%2C1707&ssl=1)

![‘Haruki Murakami Manga Stories Vol. 3’ Gives Foreboding Fiction a Macabre Makeover [Review]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Haruki-Murakami-Manga-Stories-Vol-3-Car-Attack.jpg?fit=1400%2C700&ssl=1)

![THE NUN [LA RELIGIEUSE]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheNun-300x202.jpg)

![Courtyard Marriott Wants You To Tip Using a QR Code—Because It Means They Can Pay Workers Less [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/tipping-qr-code.jpg?#)