‘Lavender Men’ Review: This Quasi-Historical, Fabulously Theatrical Film Smashes Expectations

Lovell Holder and Roger Q. Mason's stage play adaptation wrestles with history, examines modern love and imagines a queer, powerful Abraham Lincoln The post ‘Lavender Men’ Review: This Quasi-Historical, Fabulously Theatrical Film Smashes Expectations appeared first on TheWrap.

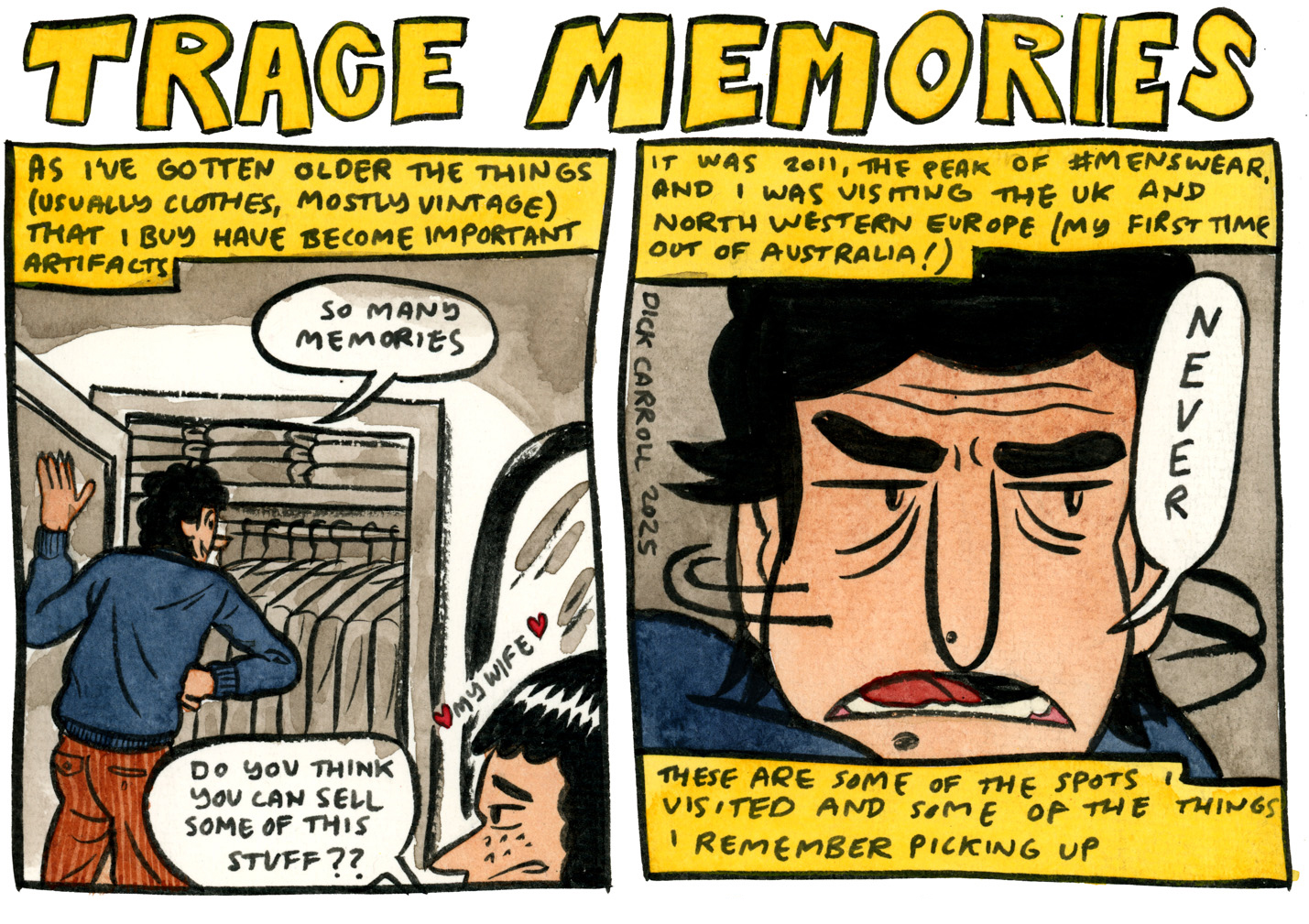

It’s rare to watch a film as rich as Lovell Holder and Roger Q. Mason’s “Lavender Men.” It’s based on a play. It looks like a play. It is intricate and complicated cinema. There are those who behave as though cinema and theater are polar opposites, and that to be “cinematic” is to evade any whiff of the “theatrical.” Remove thyself from a single location, and only then art thou in a film.

But film captures life and life takes place at the theater, at least whenever we’re in there. For those to whom all the stage is a world, those people who make live theater breathe , a film about their lives must take place on stage. And in “Lavender Men,” Roger Q. Mason plays a theater manager whose contributions to a rather unremarkable play about Abraham Lincoln are unsung, or only sung with the wrong pronouns. When the theater clears out, and after the actor playing Lincoln reveals himself to be an awful creep, Mason — playing the lovelorn, creatively stifled Taffeta — takes the spotlight.

Taffeta’s life becomes a fantasia, as they like to call it, in which historical revisionism dangles like a carrot in front of Abraham Lincoln (Pete Ploszek) and his purported lover, Elmer E. Ellsworth (Alex Esola). In real life both men met tragic ends, and as Taffeta brings them back to life on stage, Lincoln in particular rejects the offer of yet another biographical drama, sick to death as he is of dying. But this, Taffeta promises, is their fantasia, and anything can happen, history be damned. (It’s usually straight white propaganda anyway.)

I am in no way an American history scholar, but “Lavender Men” is more than history. It’s a mortal document, the vital connection between past and present. The complicated relationship Taffeta — who plays every other character in Lincoln and Ellsworth’s lives, sometimes to their consternation — has with the past, a white cisgender romanticized past, is fraught. At times Taffeta finds themselves swept up in that romance, in spite of themselves or because of themselves. But they also reject historical platitudes about Lincoln’s heroism, throwing back in his face the president’s less-frequently discussed opinions about Black people, and the enormous role political convenience played in his most legendary accomplishments.

Most pointedly, Lincoln and Ellsworth’s romance — as depicted in “Lavender Men,” at any rate — doesn’t much correlate to Taffeta’s own experience. Taffeta has no love in their life, only failed flirtations, hurtful hookups, leering fetishists, and lonely nights with an eating disorder. They know that they are beautiful, that they deserve to be loved and wanted. They also catch themselves doubting it, since there aren’t a lot of people backing them up on that self-confidence. “Lavender Men” is a kaleidoscope of self-love, self-indulgence, self-consciousness, self-respect, all while wrestling with the ongoing legacy of a man whose identity seems solidified; he’s literally engraved on the country’s currency. Taffeta controls a stage when nobody else is around. Lincoln ran a country. And apparently he had a sexier queer love life too.

All of this takes place on the stage, save for a few flashbacks to Taffeta’s disappointing relationships. Lovell Holder never shies away from the unabashed theatricality of Mason’s play. The film avoids throwing Lincoln and Ellsworth into real locations. Maybe budget was a factor, but maybe the artificiality of the theater is the point. Mason, and Taffeta, never pretend that this representation of Lincoln’s gay love affair is reality… although perhaps it was. The point is, that approach would make this Lincoln’s story, another vaunted retelling of his greatness, or at least of his significance. Lincoln would tower over Taffeta in a more conventionally cinematic narrative because “Lavender Men” would take place in his world, not theirs. So “Lavender Men” sticks almost exclusively to the stage. A magical and manipulated stage, but a stage nevertheless. And never once does it feel stodgy or limited. It feels like we — and Taffeta, and Lincoln, and Ellsworth — are in the right place, and that place demands to be filmed.

“Lavender Men” may look like a low-budget indie, and I suppose it inarguably is, but it’s got more going on than most of its expensive competition for the audience’s eyes and ears, these days or any other. It’s a film with potent ideas, inner conflict, historical imagination, dramatic challenge, queer power, human fragility, humor, sex, pathos. It’s hard to pin down exactly what makes it great, and that’s what makes it great. There’s so much to its muchness that the veneer can hardly contain it, not unlike Taffeta themself.

The post ‘Lavender Men’ Review: This Quasi-Historical, Fabulously Theatrical Film Smashes Expectations appeared first on TheWrap.

![‘Omukade’ Trailer – Thai Monster Movie Unleashes an Insane Giant Centipede Nightmare! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-30.jpg?fit=1713%2C931&ssl=1)

![Earn Krisflyer Miles on Pelago bookings [8 Miles per SGD]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/03ef670f2fa80e8e19331fbc8c26ebfa.webp?#)

![100K strategy and powering up with the right cards [Week in Review]](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/powering-up-credit-cards-1.jpg?#)