Demi Moore Found Liberation in Confronting Self-Image in ‘The Substance’: ‘What Else Is There to Tear Me Apart?’

TheWrap magazine: Playing an aging star at war with herself in Coralie Fargeat's body-horror film allowed Moore to explore layers of self-judgement — and earn her first Oscar nomination The post Demi Moore Found Liberation in Confronting Self-Image in ‘The Substance’: ‘What Else Is There to Tear Me Apart?’ appeared first on TheWrap.

For Demi Moore, there was no escaping her own image in “The Substance.” As Elisabeth Sparkle, a fading star who injects a dubious drug to spawn a younger version of herself named Sue (Margaret Qualley), Moore spends the majority of the film alone, her only scene partner her reflection in the mirror — or the giant, floor-to-ceiling portrait that looms over her living room like a shrine to the past. Over and over, Elisabeth engages with her reflection, forever dissatisfied with what she sees, which eventually is a hunchbacked, bald woman preternaturally aged due to an abuse of the sickly green solution.

These scenes presented Moore with a steep acting challenge. “I feared being repetitive. Like, is this going to be boring?” she said. “We all know our tendency is to find what’s wrong when we look in the mirror. There’s an intimacy that we experience looking at ourselves and it was definitely uncomfortable. So I just utilized that.”

To great effect. Written and directed by Coralie Fargeat, “The Substance” is a furiously gory indictment of beauty standards that women internalize to their own self-destruction. Since its debut in Cannes last May, the body-horror black comedy has been building the kind of momentum that Moore had never

experienced in her 44 years in Hollywood — the kind that landed her an Oscar nomination for Best Actress.

Part of what makes her performance hit so hard is the metacommentary she brings to it. As she revealed in her 2019 memoir “Inside Out,” she battled a severe eating disorder during her 1990s heyday, when she starred in such era-defining movies as “Ghost,” “A Few Good Men,” “Indecent Proposal” and “G.I. Jane” and suffered a media backlash when she became the highest-paid actress in Hollywood, her $12.5 million salary for “Striptease” earning her the snide nickname “Gimme Moore.” Few actresses of that time endured the level of hostile scrutiny that Moore did (her marriage to Bruce Willis was also a paparazzi magnet). So there is a certain poetic justice to earning her first Academy Award nomination for a performance in a film that takes a sledgehammer to misogyny.

“It has been quite an unexpected wild ride,” Moore said during a Zoom call from Paris, where she was doing press for “The Substance,” accompanied, as ever, by her teeny-tiny chihuahua Pilaf, who snoozed on her doggie bed during our conversation. Recalling her reaction to reading Fargeat’s screenplay, Moore, 62, said, “It really touched on so many different levels. While I am not Elisabeth, I immediately extracted from the script the potential depth of what it could bring forward, which is what we do to ourselves. That physical manifestation of the violence we can have against ourselves, to me, was just an extraordinary idea.”

It was, she said, the part she’d been waiting for, however unconsciously: “Roles find you as much as you find them.”

When you accepted your best actress Golden Globe last month, you mentioned that 30 years ago, a producer called you a “popcorn actress,” and you bought into it, not allowing yourself to hope for the critical recognition you’re currently enjoying. What would that Demi think of this moment?

That Demi probably would have been in even more shock than I was on that evening. What I would say to her is, “We did all right, kid.” [Smiles] Everything in life isn’t really what somebody else does or doesn’t do. It’s how we hold it. I didn’t misunderstand what he was saying. But I made it mean that there was a limitation to what my potential was. I don’t look back at that as any big slight to me. I think it was a genuine, honest reflection of how he saw films at that time, that there was a separation between those who could be in films that were big box office successes and those who got critical acclaim. If I had had a different perspective of being a popcorn actress, I might have been able to see that I’m allowed to have both. I think I desired both. But somehow, my deeper belief, my hidden belief, was that I wasn’t allowed.

The idea that Elisabeth is so self-hating, despite how great she — you — looks is the point: It’s never enough. At the same time, the movie does not make you look like you are 25. There are lots of close-ups under harsh lighting and nude scenes that are almost clinical in their frankness. How did you feel about those aspects?

The script was very detailed. There was no way of going into this and thinking that this was something where I was glamorized. I knew it was asking me to be seen in those vulnerable states that generally we can dress around. We want good lighting. Trust me, I love me some good lighting. [Laughs] And knowing that in fact, the flaws would be more exaggerated — there’s some of my body where she’s shooting low and wide, and I’m even wider and bigger — that was a wonderful opportunity to step out of my own comfort zone and confront those layers that still exist of our own self-judgment. On the other end of this, I actually found great liberation. Like, what else is there to tear me apart?

You’re telling a very visceral story about how we live in our bodies. When Elisabeth rapidly ages, you become increasingly covered in prosthetics. How did that affect your performance?

It’s that idea of our worst nightmares coming to light — the idea of something happening that you cannot change. It’s the whole body degrading and then you have to let go of all control. The prosthetics were definitely an easier read on paper. You’re reading it, and it’s like, “Oh, wow. Yes, that’s great.” That’s before you know you may be in the makeup chair six to nine-and-a-half hours. [Laughs] But that time allowed me to shift into that different body. Before I stepped on the set, I needed to take a couple of minutes just to look at myself in the mirror because your insides still feel like you. And so really being able to say, “Ok, yes. This is what your outside is,” and being able to align in that.

One of the scenes that comes up in every conversation I’ve had is the one where Elisabeth is in front of the mirror and violently rubs off her makeup after she decides not to go on a date. Why do you think that resonates so much with people?

Even though it’s very extreme, I think that it’s the most human [moment]. I also think it’s that arc of something, that sliver of hope that she has in that moment of breaking out of this self-imposed prison. We’ve all had moments of trying to make something a little better, only to make it worse and then trying to fix that, and then you don’t want to leave the house. The truth is, no external thing will fix what is occurring because it’s on the inside. I really felt a big part of my job in the film was to anchor it in reality because I knew that it was going to these extreme, exaggerated places. If I couldn’t bring that deeper human truth to it, then I don’t know if it would have had the same balance.

Knowing that my flaws would be exaggerated was a wonderful opportunity to step out of my comfort zone and confront layers of self-judgment.

The movie goes to dark places, but you do have some funny moments, like when Elisabeth is watching Sue on TV while cooking a massive feast, getting increasingly irritated by her. You start mimicking her.

It wasn’t written necessarily as comedic. That kind of just evolved, adding that stuff in, which made that a lot of fun for me. I loved the sabotaging that was going on because that is also what we do to ourselves: Her late-night gorging and then waking up, even though it was in the younger body, and going, “Oh, what the f— did I do?”

Yeah, the emotional eating of it all.

Been there! [Raises hand] Maybe not that gross. Coralie had very, very locked ideas of what she wanted. And it was almost a little constricting, but for some reason in that scene, because it was so chaotic, throwing the eggs [at the TV] just came out of the natural frustration of seeing Sue on TV.

To lean into the film’s theme of transformation — from the outside, it seems like you’ve been on this journey of self-affirmation, starting with your memoir, in which you really bared your soul, now to this moment of professional appreciation. Do you see it that way?

I feel like… [Coralie and I] met many times, and I think because this was such a personal story to her that a part of her was really holding tight, and I knew that talking with her about some of my experiences — even though much of my own personal body horror happened when I was much younger, ironically, as opposed to at this point in my life — I thought, You know what? Let me give her the book. Because I think seeing it in black and white, you might understand the depth of how I understood it, not from being in it, but being on the other side. The book certainly had a very healing, cathartic nature, and in a way, this is almost the completion of that.

You’ve talked about the turmoil you were in during the height of your fame in the ’90s. Do you feel like the culture has improved regarding body image?

Look, do we still have some ways to go? Definitely. But yes, there is definite change that I can see. There’s greater diversity, there’s greater inclusivity, but at the same time, there is a duality that’s occurring as social media has exploded and become part of the tapestry of our culture. There is a different type of heightened compare-and-despair. So while there is, I think, greater representation, there is still a certain aspect of perfectionism that is being sought. And it’s a challenge.

If we look at it cinematically, look at the women that are nominated this year and the roles that they’re doing. It really leaves me with such hopefulness and excitement for where we could go because what it’s saying is there’s an audience, there are people interested in these stories about these women, about different types of women in different worlds. I mean, I look at Mikey [Madison] in that role [in “Anora”]. I think about me doing “Striptease,” and look at how far we’ve come. She’s being lauded for her courage, her bravery. Obviously they are different films — I’m not comparing them. But the judgment, the shame that I experienced by playing a dancer, a stripper, versus now? I also wanted to add, I’m playing Elisabeth Sparkle, who’s turning 50. And I was 60 when we did the movie. In truth, somebody 50 really would have probably [looked] way too young. So just knowing that, in some respects, already represents that we’ve come a distance.

There’s a moment in the beginning of “The Substance“ when Dennis Quaid’s character is on the phone and he says, almost as an aside, that Elisabeth won an Oscar years ago.

I know. How funny is that?

So was this journey to an Oscar nomination all predestined?

You know what? It’s not why we do it. I never thought about that as I was doing this. But I will say, on the day we were doing the first scene where [Margaret’s] naked body has to fall on top of my naked body — I’ve got the scar that she’s sewn up in the back, and I’ve got to crawl out from under her. Literally, after the very first take of that, she said, “Oh, you’re gonna win an Oscar.” I think back now to Margaret putting that out into the universe with deep appreciation, just knowing that she was seeing something in me that I wasn’t yet seeing and how beautiful that was, because we really did look out for each other throughout the whole thing. I also know even if you do good work, not every film has this [kind of response]. I just keep saying, “Don’t make it mean too much. But also remember not to make it mean too little.” And that’s allowed me to really stay in the joy.

This story first appeared in the Down to the Wire issue of TheWrap’s awards magazine. Read more from the issue here.

The post Demi Moore Found Liberation in Confronting Self-Image in ‘The Substance’: ‘What Else Is There to Tear Me Apart?’ appeared first on TheWrap.

![‘Eyes Never Wake’ Puts Your Webcam to Terrifying Use [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/eyesneverwake.jpg)

![Official Announcement Trailer for ‘Baptiste’ Delves Into the Gameplay and Psychological Terror [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/baptiste.jpg)

![‘The Toxic Avenger’ Made an Appearance on the Green Chicago River for St. Patrick’s Day! [Video]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-16-100033.png)

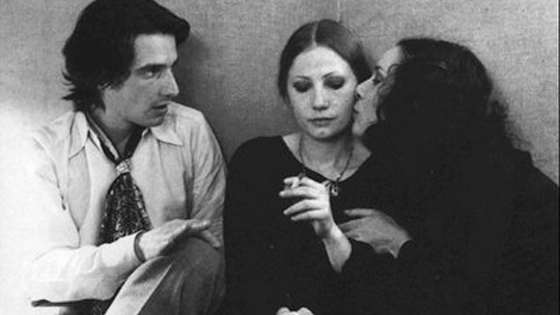

![Form Counts [MIX-UP, ANATOMY OF A RELATIONSHIP, & GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/mix-up.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)