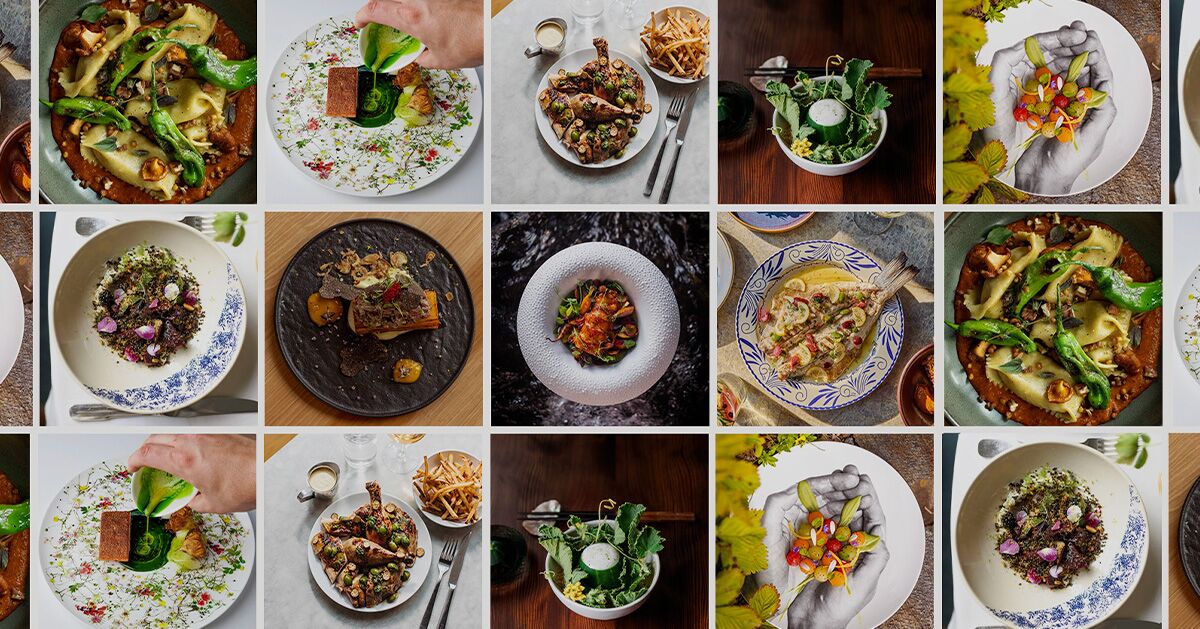

The Vallée de la Gastronomie Is France’s Tastiest Roadtrip

Taste mustard, honey, wine, bouillabaisse, and all manor of sweet treats.

Many foodies regard the Michelin guide as the authority on the best places to dine in cities around the world. However, its roots have little to do with quality cuisine: Michelin is a tire manufacturer founded in 1889, and its early restaurant reviews were designed solely to encourage Parisians to go on road trips, and thus need more tires.

Fast forward to today, and people are still gallivanting on road trips across France – but Michelin isn’t the only guide around. Nowadays, there’s also the Vallée de la Gastronomie, a newer compilation of more than 400 vetted culinary experiences travelers can explore at their leisure. The full route covers 385 miles from Burgundy, in the northeast, down to the country’s Mediterranean coast in the south.

It’s more than just restaurant recommendations: the list of culinary excursions also includes farmers’ markets, wine tastings at vineyards, and even opportunities to spelunk in caves where avant garde winemakers age their wine. It’s perfect fodder for curious gourmands hoping to plan the perfect road trip through France.

Northern Burgundy, from condiments to cassis

The “Maille” boutique at Dijon (La Maison Maille). Photo: Joao Paulo V Tinoco/Shutterstock

The name Burgundy is synonymous with wine, with more than 3,000 domaines in the region. The terroir is ideal for pinot noir (the most-grown red grape in the region), chardonnay (the most grown grape overall), and smaller amounts of gamay, aligoté, and others.

Northern Burgundy is also home to the city of Dijon, the northernmost point on the Vallée de la Gastronomie, which has a completely different association. Mustard is what put the city on the map, and when you’re there, it’s not just a condiment. It’s an ingredient in many dishes, on charcuterie boards, and even in some cocktails at Monsieur Moutarde.

You won’t have any luck finding Grey Poupon in Dijon. Local French mustard mills like Reine de Dijon and Edmond Fallot produce authentic Dijon mustards, and, like wines, their flavor nuances are influenced by the specific blend.

A good place to sample the gamut of Dijon’s famed accoutrement is at the Cité Internationale de la Gastronomie, a sprawling museum and culinary market, where mustard tastings are as obligatory as wine tastings (as is sampling their perfect complement: cheese).

Say cheese (c’est “fromage”)

Epoisses (and other cheeses) from Fromagerie Gaudry. Photo: Erik Trinidad

Burgundy’s most iconic type of cheese is Époisses, a pungent but dynamically flavorful soft cheese made with cow’s milk. Famed Fromagerie Gaudry has been crafting the centuries-old recipe since the 1970s, and its cheese-making facility in Brochon is an excellent pitstop for turophiles heading south from Dijon along the Vallée de la Gastronomie route.

But the flavor profile of a French foodie road trip need not be solely savory, salty, bitter, or sour. Sweetening the palate nearby is another Burgundy specialty: crème de cassis, a smooth, sweet liqueur made from local blackcurrant berries. Burgundy’s blackcurrant berries are considered to be among the best in France. Makers of liquor, like the family-run Jean-Baptiste Joannet in Arcenant, have tastings to appease your sweet tooth as you continue your way south.

Beaujolais, beef, and bees

Charolais beef from Maison Doucet. Photo: Erik Trinidad

Southern Burgundy is where the wine region of Beaujolais lies. Wine from Beaujolais is distinct from the majority of wines in the north, as most are fermentations of the gamay grape. It’s lighter and fruitier than pinot noir grapes.

The freshest and perhaps most well-known expression of Beaujolais wine is Beaujolais nouveau, which is shipped and celebrated worldwide on the third Thursday of each November on the same year it was harvested, per local industry rules. Whether or not a wine aged only three months is preferable, or just a gimmick, is a continual argument. But it does warrant at least a taste at wineries like Château de La Chaize in Odenas, if it’s in season. If it’s not to your liking, at least you’ve visited this magnificent, wine-producing estate, designed by the same architect as the Palace of Versailles.

However, a three-year aged Beaujolais cru might be a better pairing for another gastronomic speciality of southern Burgundy: beef. Charolais cattle, from the pastures around the town of Charolles, are desirable for their lean, flavor-forward meat. It’s on par with Angus or Wagyu beef in tenderness, but without the fat marbling. It’s masterfully prepared in a few gourmet restaurants in town, like Maison Doucet, which has a dedicated set menu honoring boeuf Charolais. The restaurant has its own herb and vegetable garden, and buys the rest from purveyors in the surrounding Beaujolais region.

Playing beekeeper in Burgundy. Photo: Thomas Chabrieres

The region also has a local heritage of nut oils, like those made from peanut and hazelnut, and they’re still being produced in small batches the old-fashioned way at Huilerie Beaujolaise in Beaujeu. For something sweeter, try the region’s honey derived from endemic flora. Beaujolais’ beekeepers, like those at the La Grappe et Le Rucher apiary in Fleurie, have plenty of ways to keep guests entertained. It’s an amusing road trip pitstop, especially if you want to don a beekeeper suit and see the honey-producing bee hives yourself.

Lyon, land of the bouchons

Pâté-en-croûte in Lyon. Photo: Erik Trinidad

The midpoint of the Vallée de la Gastronomie route is generally Lyon, the culinary capital of France: . It’s where the legendary celebrated chef Paul Bocuse elevated French fare into artful nouveau cuisine. In fact, he’s the posthumous namesake of Lyon’s gourmet food hall, immortalizing his innovative spirit. However, old culinary methods still flourish in the city’s thriving restaurant scene.

Lyon is famous for its bouchons. Historically, these eateries fed much of the working class, and inadvertently brought organ meats to the forefront of Lyonnaise cuisine, as nothing in a bouchon went to waste. Duck foie gras and veal sweetbreads are common ingredients still used today, and both are integral to pâté en croûte, a savory pastry and local specialty. It’s a dish so iconic to Lyon that there are annual competitions for its best rendition. It’s essentially a layered terrine (loaf) of various meats and offal (edible organs). It’s wrapped in dough, baked until flaky, and served like sliced bread. Bouchons also serve quenelles (a creamed, dumpling-esque dish) made with pike, a freshwater fish from the nearby Saône and Rhône rivers. It’s often smothered in a crawfish-based nantua sauce and is a recipe that originated in Lyon.

Praline brioche are a staple of bakeries in Lyon. Photo: ElisabettaCavagnino/Shutterstock

Lyon is a restaurant hub and packed with markets to explore, warranting an extended pitstop of at least a few days for any true gourmand wanting to try all the local specialities. And that includes dessert. Lyon’s boulangeries always have flaky French croissants; however, praline brioche is the more typical breakfast. Pralines are also the main ingredient of another iconic baked good – the unmistakably pink tarte aux prâlines, found in virtually every patisserie, in case you need a sweet snack before heading south.

Caves and confectionaries of Ardèche and the Rhône Valley

Spelunking in Ardèch Gorge. Photo: Erik Trinidad

The Rhône Valley is yet another important wine region of France, characterized by full-bodied red wines made from grenache, mourvèdre, and syrah grapes, all of which thrive in the region’s terroir. Those are the primary grape varieties (though many more are involved in smaller amounts) meticulously crafted into wine by the region’s 6,000-plus winemakers.

That includes one eccentric Raphaël Pommier of Domaine de Cousinac in Bourg-Saint-Andéol, who bills himself as a “wine composer.” Among his unorthodox production methods is the playing of different jazz and classical songs to affect aging, and bottles that go through this process have a QR code to link the song used. Based on his research, he swears it makes the wine more smooth and balanced, although there’s no empirical evidence to this. He also ages his wine in caves in the nearby Ardèche River Gorge to see how different bacteria in different caves will impact the taste. While many visitors to the gorge come to hike, mountain bike, rock climb, or kayak the Ardèche River, adventurous foodies can book a spelunking excursion to not only see where the wine is aging, but also sample it during a unique, sensory-deprived tasting experience.

Nougat at Arnaud-Soubeyran Confectioner

A far less taxing activity involves exercising your sweet tooth in the town of Montélimar. It may seem like any ordinary town of houses and small strip malls, save for all the artisanal confectioneries producing what the town is known for: nougat. The sweet, semi-hard treat comprises just four core ingredients (almonds, honey, egg whites, and sugar), though they’re hardly all the same. Visitors can see bakers making it in person through the observation windows at the Musée du Nougat, a permanent exhibition in the Arnaud Soubeyran nougat factory, with a history dating to 1837.

Lavender and bouillabaisse in Provence

Photo: iacomino FRiMAGES/Shutterstock

The postcard image of Provence is often a bright field of lavender shrubs, with the light purple flowers that give the region its name swaying in the breeze. And yes, many lavender farms harvest the iconic blossoms to extract their essential oils for cosmetics, creams, and lotions. However, the flowers and extracts of the harvest also have a purpose in the Provençal kitchen, where they’re used as herbs to add floral and aromatic notes to a dish. Lavender ice cream is one example. Coincidentally, it’s the dessert during picnic lunches at L’Essentiel de Lavande, organic lavender producer in La Bégude-de-Mazenc.

As you continue south toward the coast, cuisine becomes less floral and more Mediterranean, with more seafood and more influences from outside France. The dynamic port city of Marseille, the southernmost town in the Vallée de la Gastronomie, has a long history as a trading center, which made it a crossroads of international cultures. This diversity transcends into its culinary scene more than any other French city outside Paris.

Photo: GreenArt/Shutterstock

Marseille’s restaurant offerings include cuisine from Corsica, mainland Italy, Lebanon, Turkiye, the Congo, and more. However, it’s impossible to ignore the city’s most iconic French dish, especially as it’s ubiquitous on restaurant menus. Bouillabaisse, a traditional fish and seafood stew, is about as common in Marseille as rosé wine — which means you’ll find both everywhere. Rosé is the most-produced wine in Provence, but if you’re not an oenophile, you may want to try pastis. It’s a locally made, anise-flavored aperitif that has also become part of the fabric of Marseillais culture.

It’s easy to put together an indulgent (and fitting) final meal to close out a road trip along the Vallée de la Gastronomie. Start by sipping on pastis while people-watching in Marseille’s Old Port, then have a hearty serving of bouillabaisse (or perhaps a platter of Mediterranean oysters), paired with a Provençal rosé, of course. However, if you’re still hungry afterwards, you can always hit the road back north towards Burgundy. With so much culinary heritage along the way, you’re bound to have a completely different experience — provided you still have room in your stomach. ![]()

![First-Person Psychological Horror Title ‘The Cecil: The Journey Begins’ Arrives on Steam April 3 [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cecil.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![‘It Ends’ Review: The Kids Are Not Alright In Alex Ullom’s Evocative Existential Horror Debut [SXSW]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/12223138/it-ends-sxsw.jpg)

![Silver Airways Can’t Pay for Planes—So It’s Firing Pilots Instead [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/silver-airways.jpg?#)

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)