Talking point: Investment choices and finding balance in North American airport concession programmes

The viability of airport concessions, the structure of retail programmes and the attractiveness of tender bids all came under the spotlight during a compelling conference session at the IAADFS Summit of the Americas in Miami last week. We present highlights.

USA. The viability of airport concessions, the structure of retail programmes and the attractiveness of tender bids all came under the spotlight during a compelling conference session at the IAADFS Summit of the Americas in Miami last week.

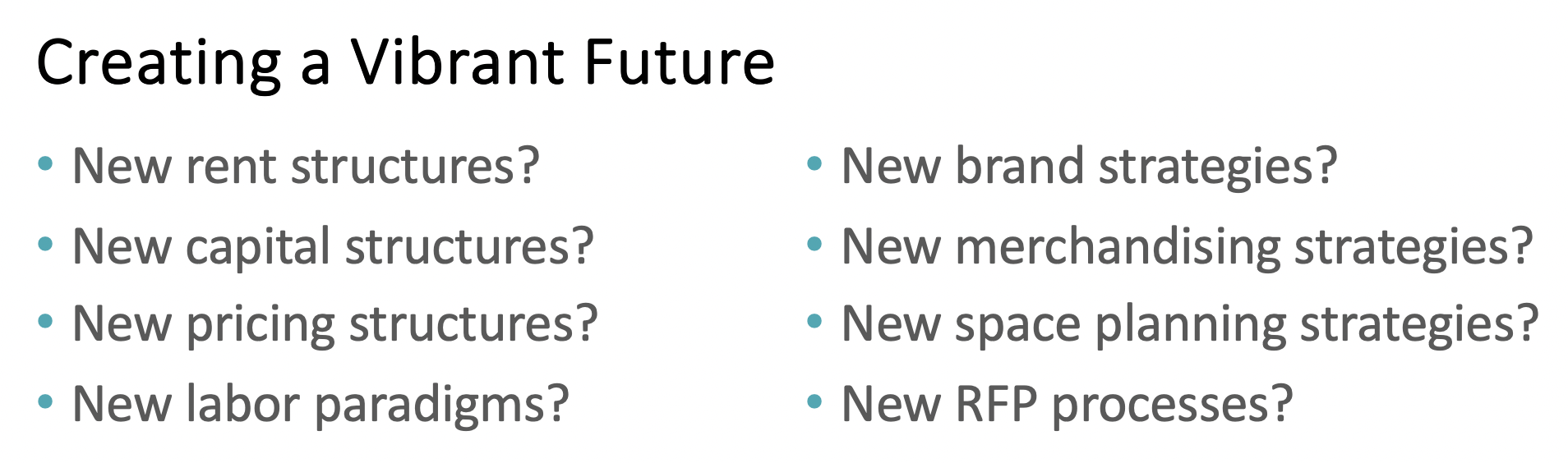

A panel discussion titled ‘Creating a Vibrant Future’ was co-organised by the Airport Restaurant & Retail Association (ARRA) and The Moodie Davitt Report and centred around a call for bold strategies and new business models to drive the future of airport retail in the region.

Speakers included Paradies Lagardère Chief Development Officer David Bisset, Byrd Retail Group President & CEO Judy Byrd, Avolta Chief Development Officer North America Derryl Benton and ARRA Executive Director Andrew Weddig, with The Moodie Davitt Report President Dermot Davitt as moderator.

Setting the scene, Weddig said: “In 2025 the US airport concessions industry is at a crossroads for all of our operators across retail, duty free, duty paid, as well as food & beverage.”

He highlighted four key facts. First, wage rates for concessionaires’ associates have climbed +57% since the pandemic.

Second, construction costs have been soaring. Some 17% of ARRA members report that their costs have climbed more than +50% in recent years.

Third, interest rates are back to levels not seen since the 2008 financial crisis. Weddig said, “It may be that the period between 2008 and COVID was in fact the abnormal period and that we are looking at 4-5% interest rate levels as standard.”

Finally, sales growth has stalled among concessionaires. From 2011 to today, the share of passenger spend on speciality retail has fallen from 18% to 11%, although food & beverage has grown its share. In summary, Weddig noted, concessionaires are struggling to keep up as increased wages, higher interest rates and stagnant sales mean they are no longer making returns on investments.

Bisset summarised the challenges through a detailed analysis of the landscape for Requests for Proposals (RFPs), and how Paradies Lagardère has responded to it.

“The environment we see today is really a by-product of unnatural delays in the market coming from COVID-19,” said Bisset “There was really no RFP development from 2020 all the way to 2022 and even in most of 2023 most airports were just trying to get their traffic back to 2019 levels. It was not an optimal time to launch an RFP in North America.

“Last year, from our tracking, there were 147 RFP packages across duty-free and duty-paid retail and food & beverage in North America. That was three times higher than the averages the market has typically seen before.

“That is an extraordinary number but what’s also interesting is that it will continue through to 2027, if not at this rate then at least at double the normal business development cycle. And what makes this cycle very different is that we are now facing interest rates that have doubled, and capex rates today are also +40% higher than before.

“So we have this immense business development opportunity but on very different economics. I believe we are in a situation today where for the first time, there are more opportunities than there is available capital in the market.”

Bisset revealed a key number, saying that even in an environment with more RFP opportunities than ever, Paradies Lagardère had passed up 40% of them.

“We passed on those opportunities because the economics don’t add up. We want to be able to get that rate of participation up in our business so that we can get a healthy and competitive market.”

This ARRA video outlines the challenges facing concessionaires today. Click here for more ARRA comment on the challenges facing airport concessionaires; for more content see the ARRA website.

Derryl Benton laid out the challenge by displaying a US$1 bill and outlining how this breaks down with a new business opportunity.

“I kick off my business with a Dollar, but if I’m paying a royalty, whether that’s in F&B or speciality retail, then really I’m starting with 95 cents, if we take the royalty fee as 5%. Then I’ve got to fund my costs of goods – whatever I sell I have to pay for – so let’s call that 30 cents.

“Now the landlord wants rent, so let’s say occupancy in this example to cover rent, the electric bill and other expenses will be 25 cents.

“The on top of that we have labour which has gone up, according to ARRA, by +57%.

“With all of that in mind, of the 100-plus RFPs that went out last year, the return of responding to those is not feasible.”

Judy Byrd said the sector had already reached an “inflection point” before the pandemic and was facing crisis with rising rents, construction costs, tight pricing policies and other factors.

“Since then it has only got more acute,” she added. “I come to this as someone who is investing in opportunities at airports and who has consulted to over 100 airports across many projects. As a small business partnering with global companies, when they catch a cold we catch pneumonia. We face the same cost base but we have less ability to sustain those costs, plus we have debt accumulated from the COVID years and far less access to financing than the major players.”

She added, “We are at a point where airports have got to lean in and look for a more equitable allocation of the risk-reward model in their RFPs. If you treat it as a one-way street, you are either not going to get responses to your RFPs or the responses that you get are going to be sub-optimal, and you’ll be trying to fix it down the road or renegotiate deals, which is not the scenario that we want to have. Ultimately in that case, the biggest loser is the passenger.”

Speakers addressed the “elephant in the room” – the topic of labour, as wage rates continue to rise.

Weddig noted: “We see a marked increase in the number of mandated minimum wages through city ordinances or contracts that have gone far above market conditions.”

Bisset said, “We care about our business and we care about our employees. And every employee is entitled to a fair wage and a quality of life.

“If I was to ask everyone in the room what their salary increase was in 2024, most would probably say it was around +2-3%, in line with inflation.

“Many of our large airports in North America saw increases of between +6% and +11%, but that is not for one year, it’s for five consecutive years.

“How do you pay for that? There is a myth in our industry somehow that the top-line figures we see translate to some unnatural or super-high profitability. It’s not the case. Most airport contracts sit between 5% and 10% profitability.”

He noted that if wage increases rise at the above rates over five years, the profit line for a concessionaire is likely to narrow to almost zero.

“How do we address that? There are really four levers you can use here. You can raise prices to the consumer. But the challenge here is that from the second half of 2024 there was an observable decline in spending from consumers in North American airports, so with economic pressure on consumers, it’s difficult to continue to use pricing as a way to pay for your cost pressures.

“The second option is reduced rents but obviously airports depend on those rents to pay the bills.

“Then you have profits, an area in which concessionaires are taking a hit, which means they are also very concerned about whether they proceed with an RFP or whether they stay or leave a market when the contract elapses.

“And lastly, as brands will be aware, there is the conversation with concessionaires about the need for more margin.

“Now all four of those represent unpleasant outcomes. Today, when we are choosing to pass on 40% of RFPs, the number one challenge is typically term. But we have seen good things happening in term recently, extended in some cases by airports in their RFPs. And following that, the number one cause of whether we would go for an RFP or not is the extreme staff cost involved.”

Moving the conversation forward about what solutions would help concessionaires, and in turn drive enhanced investment, Benton said: “The headwinds are real so the question is what do we need to keep doing business?

“The airports can still borrow money at a cheaper cost and longer term than we can so I need the space I’m moving into fully ready as a ‘white box’ for me to build it. I’ve got to build out the space and merchandise the space. What I cannot do any longer is fund airport infrastructure upgrades. I can’t upgrade their piping. I can’t upgrade their data lines.

“I need a clean white box with all of my utilities included so I can put that luxury bag, that fragrance and those confectionery items into it. I can build from the white box in, but I cannot build from the white box out.”

Offering a further pointed proposal, Benton said that airports could consider halting the issuing of RFPs for a period until the industry normalises.

“The pandemic came and caught us all off guard. In turn, our federal government gave our airport partners three buckets of money. 90% of their staff payroll was paid, which kept those employees out of the unemployment line. Brilliant. It saved a lot of money and kept people’s pay cheques flowing.

“The second thing is the government paid the airport’s debt service. The third thing they did was to say, if you have an airport project coming out of the ground, we will fund that project.

“So if I’m an airport, they paid the mortgage, funded my payroll and they allowed me to continue the renovation of my home.

“Then three years later, all these employees came back to work and we had pent-up demand for RFPs that would normally have been spread over three to four years.

“It was not a natural situation. So today, we cannot cover the headwinds we are facing and invest at the same time. So I say let’s slow down the RFPs for now. We can still renovate and modernise but we don’t need a flood of tenders. Let me allocate that capital toward operations, because I can’t build the house plus cover the cost of running the house.

“Plus most of our bids have 30% small business participation. That rule requires that partner to put in 30% of the risk. It’s difficult to put these partners in that deal right now. The headwinds are strong so my view is that we should hunker down.”

Reacting to that proposal to slow down or halt RFPs, Byrd said: “The market will continue to act and RFPs will keep coming.

“What I would flag is that the airports need to do better analysis on the cost of doing business. The airport team, or the consultancy team, needs to fully understand the cost of doing business at the airport, and knowing the economics of each deal.

“You have got all these levers that you can play with. There is rent over here, construction costs over there, pricing policies, labour and more. When the math does not compute, something has got to give. Every airport in America needs to run their programmes through that analysis and test before any RFP hits the street.

“The other thing that is an issue is the over-building of programmes. You should not just say I will fill the space I have.

“I also believe we have too many third-party developers in the market. I have long experience working with Avolta, Paradies Lagardère and others, and they have great know-how in their teams. They know what sells and what doesn’t sell. They know how to build beautiful stores. They know how to put together marketing programmes.

“Yet airports feel they need to have another ‘middle man’ in the model, incentivised to set the rents as high as they can because that’s how they get paid. At the same time airports are telling us they want the most exciting concepts and designs and they want the small businesses to thrive. They want it all but it doesn’t pencil.”

Addressing how to reinvigorate the RFPs process, Bisset homed in on some of the 60% of tenders that the company responded to, highlighting some groundbreaking, progressive thinking among airports.

“Profit sharing and joint venture is not a model you see very often in North American airports but we have one that is very successful at Charlotte Airport since 2011. What was reassuring in 2024 was that two other airports approached us to understand that model in greater detail. It’s clear there are airports seeing this as a viable way forward and who want to be aligned as true partners versus the landlord model.”

He also addressed how space is allocated. “We know from studies that 60% of North American airport sales are food & beverage in airports, 30% is duty-paid retail and about 10% is duty free. So does the square footage in airports typically replicate their sales percentage?

“No it does not, but what we are seeing today in a lot of successful RFPs is that square footage is starting to reflect those sales much better than before. And for people in a duty-free mindset, it raises the question of how to have more hybrid opportunities, get more F&B experiences inside duty free, and slow the passenger down by creating an overall hybrid environment.”

Another encouraging signal has come from engagement with the handful of major consultancies that advise most North American airports on their RFPs, added Bisset.

“We are seeing these consultancies starting to reach out to ask concessionaires about the cost of capital per square foot at certain locations. Last year, we completed 271 construction projects so there are very few companies – beyond perhaps us and Avolta – that have more benchmarks in capital right now for our industry, so it gives me a lot of confidence seeing consultancies asking that information.”

Term of contract is another factor where some evolution is taking shape.

Bisset said: “We started talking about the pressure around capital in a big way about 18 months ago, and already we see now that F&B RFPs are typically coming out with terms not at seven to ten years, but 12 to 15 years. We are also seeing ten years quickly becoming the norm for a retail contract. That means that people are listening to these conversations and are recognising that addressing term improves response rates.”

Citing one example of an airport company that has done something fresh and exciting with its RFP, Bisset named San José International Airport, which ran a process in late 2024, with results announced recently.

“The head of the concessions programme is Rebecca Bray, who is an outstanding industry executive. She did three things that made that RFP unique that we had not seen before.

“One, local products are something that are very hotly demanded by stakeholders of airports. Unfortunately, our data confirms that sales being generated from those products are quite low. So what the airport said is, we understand that this is not the most profitable category for everybody, but we require it for sense of place. So they did the obvious thing that no one else has done: they placed lower rent on local products.”

The second idea related to the industry practice of centralised receiving and distribution centres (CRDCs). Bisset noted, “Airports cannot manage the amount of truck traffic and product movement that occurs airside, so they give the contract to a company to run this for them. The problem is that the cost is quite high, and gets passed onto concessionaires and ultimately onto suppliers for higher margins.

“So the airport granted everybody an automatic two-year contract extension. They realised that they needed to keep everybody happy and the overall financials economically viable.”

Third, the airport examined the productivity of the retail programme and made dramatic changes by removing some individual stores, combining them into larger department-style outlets.

“By doing that, you are optimising capex, reducing the overall labour cost of running these individual stores and getting synergies at a higher level, and in return, the airport was able to increase rent.”

Byrd reinforced the importance of flexibility among airports. “As they are writing these RFPs, they should think about all the different areas that they can touch to make this business feasible. Turn the space over in a usable condition with utilities stubbed in.

“It’s also time for airport RFPs to be really responsive to the cost of doing business at their airport. If concessionaires are saying, our numbers don’t pencil, maybe airports need to be looking at stepping up percentage rent instead. All of this gets to a sharing of the risk.”

Bisset returned to a theme he raised during a compelling session at the Airport Food & Beverage + Hospitality (FAB+) Conference in Ontario, California last June, around the balance of brands in a retail programme. At the time he noted a disconnect between airports demanding local concepts in their RFPs and the ability of many of those local concepts to deliver commercially.

In Miami last week he said: “Recently we have seen a rebalancing between national, local and proprietary airport brands. We started to see a lot more of that happening in the back half of 2024 and I would like to think that might have been due to some of the things that we are talking about now, and did at FAB+ 2024, while revealing some of these costs and the overall direction of the market.”

Elaborating, Bisset said: “In the past 18 months I have sensed that if we talk about the issues and we find solutions together, it does create change. It is happening with capital and term as I said. We can see it.

“But we cannot manage what we don’t measure. So having these open conversations proves to me that people are listening and we are seeing the change. Let’s keep having these conversations and sharing information.”

Weddig said that “change has to come from some place”, with closer alignment between airports and concessionaires on how programmes are financed an important contributor.

“When the airports understand and are involved in the income statement and the balance sheet, they better understand how to develop programmes.

“Today, if you are being paid a percentage of sales, your main focus is the top line, the revenue line, and that’s the case with many airports. So a 20,000sq ft programme may have the best economics overall, but from my perspective as an airport, 24,000sq ft is even better, because that is 4,000sq ft more generating revenue, generating rent, except for the fact that you pay no attention to the rest of the balance sheet.

“We may be getting to a point where some programmes are becoming too big. When Judy and I were doing consulting for airports building their programmes 20 years ago, we had a metric that was around 6-7sq ft per 1,000 enplanements as the ideal size. Just the other day, I spoke with a current consultant in the industry who said that 10-12sq ft is ideal.

“So you have a big step up in the costs of building that programme, a big increase in labour to support that programme, but you are not generating that same increase in sales. Some programmes have too many stores and concepts, which do not support themselves.”

Concluding, he said: “What these things we have discussed do – the profit-sharing model, extending the term, building out the ‘white box’ – is enhance the partnership value in this industry, and align where the airports and the operators are together, instead of where they are apart.”

![‘Final Destination’ at 25 – Director James Wong Reflects on Cheating Death [Interview]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/finaldestination-alilarter.jpg)

![‘Cam’ Puts the “Work” in “Sex Work” [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cam-Movie.jpg)

![Form Counts [MIX-UP, ANATOMY OF A RELATIONSHIP, & GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/mix-up.jpg)

![JFK’s Soho Lounge Staff Suggests Guests Share A Shower—No, Really [Roundup]](https://boardingarea.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/f463f380236d69d7f868c9386a4c7ff7.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)