South Africa’s New Cheetah Trail Is Chance to See the ‘Big 5’ on Foot

As a South African, I grew up on safari, whether in the back of my dad’s 4×4 or bumping around the loftier heights of a hotel Jeep. Now, as an adult still living in South Africa, I still adore seeing animals in the wild. So when I heard about the new “Cheetah Trail” walking safari […]

As a South African, I grew up on safari, whether in the back of my dad’s 4×4 or bumping around the loftier heights of a hotel Jeep. Now, as an adult still living in South Africa, I still adore seeing animals in the wild. So when I heard about the new “Cheetah Trail” walking safari experience at Samara Karoo Reserve, it was a no-brainer that I wanted to be among the first to do it. Safari? Sounds good. Walking? Love it. Cheetahs? Say no more.

I left Johannesburg on a red-eye flight, headed for Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). I met my group, and we transferred by car to Samara, about a 2.5-hour drive away. We then bundled into a classic safari Jeep to be taken to Samara’s private “Plains Camp” – and that was the last we saw of vehicles for the day. We had lunch, donned our hiking boots, and set out.

Walking through Samara Karoo Reserve on foot that afternoon felt borderline transformational: “I am one with nature. I am serenity made flesh,” I thought.

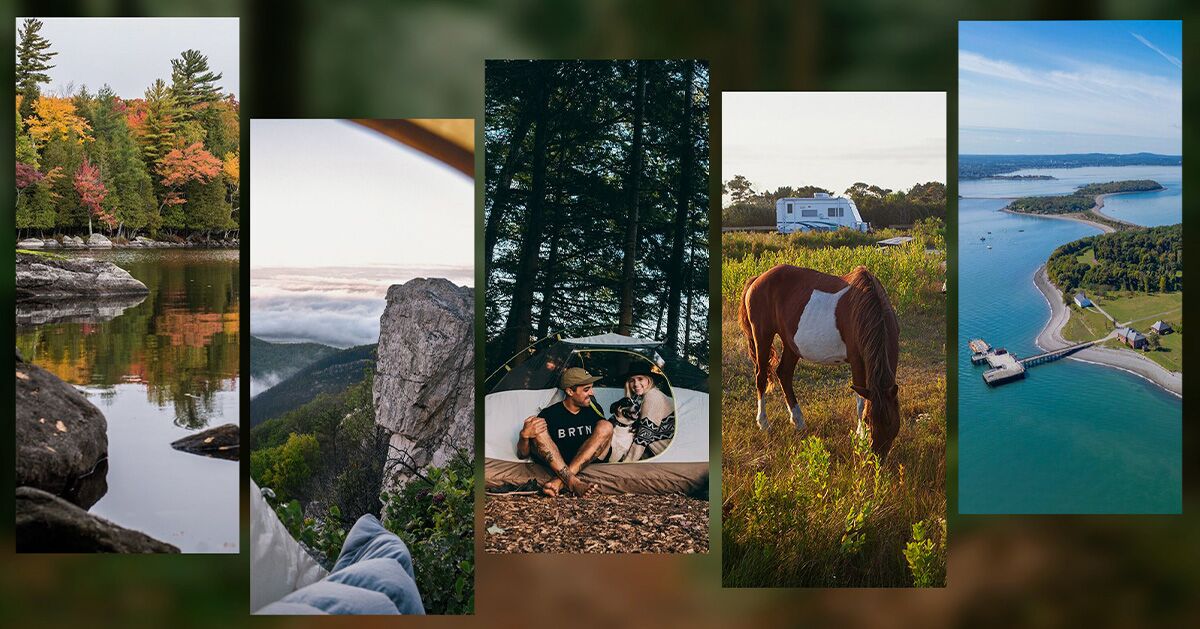

The author on safari, and the landscapes of the Karoo. Photos: Tayla Blaire and Samara Karoo Reserve

That lasted for around six hours — until we left the dining tent in the unfenced Plains Camp. We were following one of our rangers as he led us back to our tents with a high-beam flashlight.

During our safety briefing earlier in the day, he taught us nonverbal hand signals, explaining that yelling in the middle of the bush is not conducive to remaining, well, whole. So when he held up a clenched fist, it felt like a test.

“What is it?” I whispered, grinning. I love acing tests.

“Grumpy,” someone whispered back.

While not a strictly inaccurate assessment of my character, they weren’t talking about me. Our guide spotted “Grumpy,” a solo male white rhino, earlier on our first walk from afar. His nickname was bestowed thanks to his notably irritable temperament.

Grumpy (not pictured) is a solo male white rhino. Photo: Yulia Lakeienko

We remained in place, unwilling to budge an inch and disturb the dirt at our feet. I scanned the silhouette of our tents that sat no more than 100 feet away. “Who’s tent is the rhino blocking?” I wondered, before correcting myself that we were actually blocking him. I felt that glowing “one with nature” smugness again. “This is his home, not mine,” I thought.

But quickly, a crunch snapped my musings, replacing it with stomach-vaulting dread. “Grumpy isn’t by the tents,” I realized. “I wished Grumpy was by the tents,” I thought. But Grumpy is 10 feet away, his enormous behind towering like a boulder.

My mind helpfully replayed every headline I’ve ever read about charging rhinos, every memory where our car had gotten too close to one on safari and my dad would quickly reverse, swearing, while my brother and I shrieked from the back seat. But there’s no car to hide behind in Samara Karoo Reserve.

“Unfenced” is an adjective easy to dismiss when reading about a safari camp, but this is the reality: 5,000 pounds of Grumpy just steps away with no metal barriers or fences in sight.

I missed our guide’s next hand signal, too busy imagining who should read my eulogy. But soon, we started walking again. Refusing to look elsewhere, I watched Grumpy ignore us, blessedly finding the tasty, long grass by a thorn thicket more interesting. Our guide soon led us to safety, and I climbed the steps to my raised tent, zipping the canvas shut and collapsing on the bed before letting a strangled laugh break free.

Photo: Samara Karoo Reserve

I’ve done short bush walks and walking safaris before, spending an hour or so ambling away from my lodge, smiling beatifically at springboks, kudus, and zebras that scampered away. But this was something else.

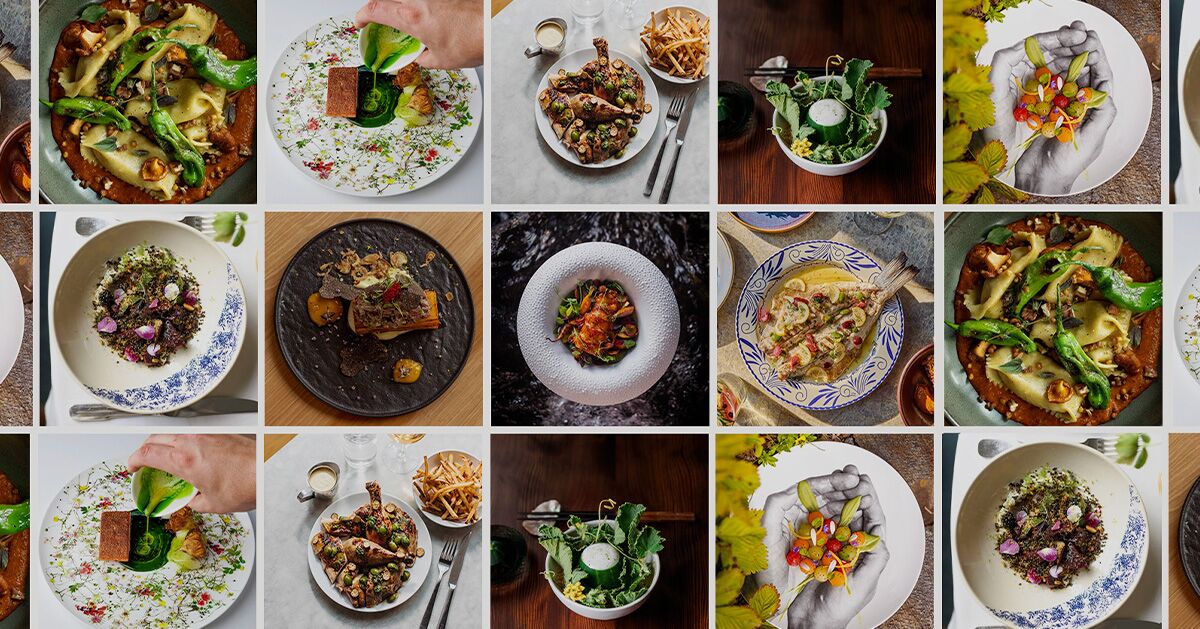

Samara’s newly launched Cheetah Trail is a three-night, four-day trip perfect for someone who feels like they’re “over” the traditional safari game drives. It’s slackpacking, meaning you only need to carry your snacks, water and sunscreen in a bag each day, rather than lugging a tent, clothes, pots and pans, and more with you. The base is Plains Camp, an off-the-grid, unfenced tented camp in a Big Five reserve with views of the distant, blue-tinged mountains and sprawling orange-earthed plains. Walks average about eight miles each day and depart from camp, accompanied by expert guides.

Plains Camp is the base for the Cheetah Trail, though hikers also stay at more rugged bushcamps. Photo: Samra Karoo Reserve

With a minimum age of 16, Samara seemed to take safety seriously, though I still found myself wishing for my sense of long-lost teenage invincibility. There’s nothing like nearly walking up the backside of a rhino to remind you how fragile you are. Walking safaris are inherently risky, and our encounter with Grumpy was a sobering reminder of what it means to walk on the wild side.

On my second day, we left the safety of our tents and headed for the mobile camp. We set out into the wilderness again, backpacks carrying just water and light snacks as we sent a change of clothes and some overnight toiletries ahead with a support vehicle.

As I stepped over eroded soil and thorns, it blew my mind that I was on safari in the Karoo, an area now known for lamb farming and the occasional windmill. That wasn’t always the case in the Karoo, however. It once teemed with wildlife, such as black-maned lions, rhinos, elephants, cheetahs, and even the now-extinct quagga.

Hunting and overfarming destroyed the animal population (and planet), but in 1997, South African Sarah Tompkins and her husband Mark heard a story about the Karoo’s former glory days, and said their their hearts broke at the tragic loss of species. But it planted an idea. Sarah and Mark bought Apieskloof, a farm in the heart of what’s now Samara Reserve, and expanded from there. They restored 67,000 acres of land in the Karoo and slowly implemented a rehabilitation program with wildlife reintroductions. Lions, leopards, black and white rhinos, and elephants now roam Samara.

Sibella caring for one of her cubs in the Karoo. Photo: Samra Karoo Reserve

Despite the myriad wildlife, Samara has become synonymous with cheetahs, largely because of the legacy of Sibella. Sibella was a wild cheetah who survived a brutal attack by hunters and their dogs. Clinging to life, she was rescued by the De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Trust, and brought to Samara for rehabilitation. In 2004, she stepped onto the soil as the first wild cheetah in the Karoo in 130 years. More followed, and despite her injuries, Sibella became known as the “Mother to the Karoo.” She thrived, birthing 19 cubs in her lifetime. Through this, she contributed 2.4 percent to South Africa’s wild cheetah population: a testament to how crucial cheetah conservation efforts are. Sibella died of natural causes in 2015 at the age of 14.

Elroy Pietersen, one of our trackers, remembered Sibella well. “For a few months, I followed her every day on foot,” he said, recalling her rehabilitation and how she began to hunt for herself after healing. “After her first litter, she brought her cubs to the Karoo Lodge, as if to show appreciation. She and her litter lay there, right in front, for a whole morning.” Pietersen has been at Samara since he was a teenager, now using his decades of experience to mentor younger guides and trackers — and look after city slickers like me.

I kept my eyes peeled for Samara’s famous cheetahs, though it felt like the landscape was mocking me by offering countless tortoise sightings instead. We keep to a brisk pace, moving past the sun-bleached bones of antelope carcasses. Some were intact with horns spiraling from the skulls, others scattered by predators long past.

Outdoor showers at Plains Camp put visitors in the heart if the wilderness (while naked). Photo: Samara Karoo Reserve

It’s another cat that snatched my attention soon after reaching our mobile camp, when I heard a lion’s low rumble. I was washing off beneath a tree, but we’d seen the tracks from several lions while walking earlier. After some swift mental calculations, I determined the lion to be approximately “way too close” and proceeded to take the world’s fastest bucket shower before returning to the bonfire wild-eyed (and still damp). No one else had heard the lions, meaning I am either paranoid, or the de facto best tracker in camp. I choose the latter, settling into a camper chair with a G&T.

After a delectable braaied (barbecue) dinner, I fell into my camping cot, remarkably comfortable with a mattress, covered by mosquito nets hanging from gnarled branches twisting in front of the sparkling constellations overhead. It feels utterly exposed to be under the open air in the Reserve, yet I sank into sleep, grateful to my guides for keeping watch in shifts.

Camping under the stars on the Cheetah Trail. Photo: Tayla Blaire

The next day, we returned to the wind-whipped Plains Camp, when we heard that the Kalahari Boys, a well-known duo of male cheetahs, had been spotted not far from us. Unwilling to miss our shot at seeing these exquisite, vulnerable animals during the last dregs of daylight, we opted to jump in the game vehicle. My feet whimpered their thanks at the respite, though it was mere minutes before we were climbing out again.

The plain ahead was empty, with low, grey clouds skimming the distant hilltops. Pietersen waved to our vehicle in the far distance, and we jumped out, walking single-file to him with another guide at our backs. It’s a well-rehearsed dance at this point, designed to have us emulate a wide, multi-limbed (if fairly short) tree. (I’m one with nature. I am a tree.)

I strained to spot the cheetahs on the horizon and was startled when one of the Kalahari Boys suddenly stood up, a bright, bloodied carcass dangling from his jaws. Once again, I’d been looking too far when I should have been looking just yards away. His brother stood up, too, snapping his jaws to grip what was left of the baby gemsbok. They teamed up, just as they likely did for their kill, see-sawing to rip the meat further. One thin, unravelled intestine was dangling close enough for us to touch.

Cheetah Trail visitors may be lucky enough to see the reserves resident cheetahs from a close distance. Photo: Samara Karoo Reserve

We resisted the urge. We are trees, after all.

According to Samara Karoo Reserve co-owner and founder Sarah Tompkins, the Cheetah Trail was designed to drive awareness of the plight of this endangered species. “Tracking cheetahs on foot is a deeply humbling experience that showcases the majesty of these animals and their vulnerability in the face of a changing world,” she said.

“Humbling” does seem like the correct word. Between bites, the Kalahari Boys scoped us out. Our guides remained alert, but unflappable. The cheetahs at Samara are habituated and used to humans being close, but not too close. It’s a legacy left by Sibella, who had a unique relationship with humans.

Photo: Samara Karoo Reserve

The cheetahs are far from tame and it’s essential to respect their space, but it’s the closest I’ve ever been to the endangered, magnificent animals. A thin tracking collar sat around one’s neck, serving as a reminder of the careful efforts to protect Samara’s current cheetah population of 13.

We stood there for more than an hour, watching them plough their way deeper into the carcass, blood staining their jaws and contrasting with the black tear marks running from their inner eyes to their whiskers. When we started losing light, we picked our way through the brush back to the vehicle. I’d lost sight of them already when I looked back, their camouflaged spots blending into the Karoo.

But I knew they were still there. For now, at least.

How to visit

Photo: Samara Karoo Reserve

Samara’s Cheetah Trail is a three-night, four-day trek, available between September and May. Camps have no Wi-Fi, electricity, or cell service, and hikers need to be ready to walk eight to 10 miles a day on variable terrain.

Samara also operates the Karoo Lodge, for travelers interested in visiting but not keen on bush camping. Stays include lodging, meals, and game drives. ![]()

![First-Person Psychological Horror Title ‘The Cecil: The Journey Begins’ Arrives on Steam April 3 [Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cecil.jpg?fit=900%2C580&ssl=1)

![‘It Ends’ Review: The Kids Are Not Alright In Alex Ullom’s Evocative Existential Horror Debut [SXSW]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/12223138/it-ends-sxsw.jpg)

![Silver Airways Can’t Pay for Planes—So It’s Firing Pilots Instead [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/silver-airways.jpg?#)

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)