In Ancient Bulgaria, the Tombs of the Elite Were Filled With Golden Treasures

The reign of Seuthes III began with blood and strife. The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace, which made up much of the territory of modern-day Bulgaria, had been invaded by Macedon some decades prior. Now, a Macedonian governor ruled the kingdom in place of its native kings. Seuthes, a member of the Odrysian royal family, had revolted against the Macedonian governor of Thrace and, with the death of the Macedonian leader Alexander the Great in 323 BC, he took back control of his country, built a new capital in central Bulgaria, and named it after himself: Seuthopolis. He remained on the throne for more than three decades and upon his death toward the end of the fourth century BC, his descendants granted him a splendid monumental tomb. A tomb whose majesty befitted his status, but which also was constructed within a long tradition of unique Thracian royal burials. The Thracians first appeared in the territory of modern-day Bulgaria and Romania during the Late Bronze Age. They remained disparate tribes and cultures, often fighting internally for control of resources and territories. It was not until the foundation of the Odrysian Kingdom in the fifth century BC that many of the Thracian tribes came together under a single ruler. This kingdom lasted in one form or another until Thrace was conquered by the forces of Rome during the second and first centuries BC. The Thracian lands were full of valuable resources, which led many Greek city-states to set up colonies on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast and further inland. There, they signed treaties and traded with the Thracian tribes for silver, gold, timber, furs, and even Baltic amber. Some cultural exchange of beliefs and faiths naturally followed, but the Thracian afterlife beliefs remained distinct from those held by their Greek guests. In the same way that there were multiple different Thracian tribes, so too were there different beliefs about what happened to a person after death. The Gaeta, one of the largest Thracian tribes, believed that dead nobles and rulers would go and join the god Zalmoxis as immortal heroes. For common folk, the best way to achieve this desired Afterlife was to fall bravely in battle, or to win a lottery by which, every five years, one individual would be sacrificed and sent to Zalmoxis as a messenger from the world of the living. The desire for the afterlife to be a place of eternal life, banqueting, feasting, and joyful things is reflected in the burial customs of the Thracian elite. Their monumental tombs took the form of underground chambers and passages, built from stones, bricks, or wood, and covered with soil to form imposing mounds. Often built on flat ground, these monuments could reach impressive heights—the largest non-royal tomb, the Shushmanets Mound, was more than 60 feet tall—and were visible across great distances. Under the mounds, the tombs consisted of an antechamber where funerary offerings could be deposited. This area was also where horses were often sacrificed and interred to accompany their owner to the Afterlife. The antechamber connected to a burial chamber via a narrow passage. There, in the heart of the tombs, the deceased would be laid out on a couch or funerary bed. They would be dressed in their finest clothes or armor, and the burial chambers themselves were sometimes decorated with vibrant frescoes showing religious scenes, or with delicately carved stone sculptures. The builders of the monumental tomb of Seuthes III really went above and beyond. First, they selected an important religious site, a temple built near what is today the town of Kazanlak and what, in ancient times, was the main seat of Seuthes’ power, his capital of Seuthopolis. The temple had been in use for more than two centuries, but the builders repurposed it as a grave for their king. The tomb, known today as the Goliama Kosmatka Mound, consists of a long entry corridor leading to a suite of anterooms that contained, as tradition dictated, a horse burial. The burial chamber was built from large stone blocks to resemble a colossal sarcophagus, and inside it was placed a model funerary bed upon which Seuthes’ body was laid. The king did not go empty-handed to the afterlife. Far from it. His tomb contained a wealth of treasures, including the king’s helmet covered in gold leaf, his armor, sword, and spears. Wine amphorae were also placed in the tomb along with golden drinking cups and a silver-gilt scallop shell used to hold toiletries and perfumes that may have belonged to Seuthes’s queen, Berenike. Perhaps most stunning is the bronze portrait of the king with inlaid milky-white stone eyes that seem to stare fiercely back at the viewer. Many Thracian treasures were looted from their tombs long ago, but by sheer luck, the tomb of Seuthes III remained unbothered. It was discovered by archaeologists in 2004, allowing its treasures to be recorded, photographed, and properly displayed in the National Archaeological Museum in Bulgaria

The reign of Seuthes III began with blood and strife. The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace, which made up much of the territory of modern-day Bulgaria, had been invaded by Macedon some decades prior. Now, a Macedonian governor ruled the kingdom in place of its native kings. Seuthes, a member of the Odrysian royal family, had revolted against the Macedonian governor of Thrace and, with the death of the Macedonian leader Alexander the Great in 323 BC, he took back control of his country, built a new capital in central Bulgaria, and named it after himself: Seuthopolis.

He remained on the throne for more than three decades and upon his death toward the end of the fourth century BC, his descendants granted him a splendid monumental tomb. A tomb whose majesty befitted his status, but which also was constructed within a long tradition of unique Thracian royal burials.

The Thracians first appeared in the territory of modern-day Bulgaria and Romania during the Late Bronze Age. They remained disparate tribes and cultures, often fighting internally for control of resources and territories. It was not until the foundation of the Odrysian Kingdom in the fifth century BC that many of the Thracian tribes came together under a single ruler. This kingdom lasted in one form or another until Thrace was conquered by the forces of Rome during the second and first centuries BC.

The Thracian lands were full of valuable resources, which led many Greek city-states to set up colonies on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast and further inland. There, they signed treaties and traded with the Thracian tribes for silver, gold, timber, furs, and even Baltic amber. Some cultural exchange of beliefs and faiths naturally followed, but the Thracian afterlife beliefs remained distinct from those held by their Greek guests.

In the same way that there were multiple different Thracian tribes, so too were there different beliefs about what happened to a person after death. The Gaeta, one of the largest Thracian tribes, believed that dead nobles and rulers would go and join the god Zalmoxis as immortal heroes. For common folk, the best way to achieve this desired Afterlife was to fall bravely in battle, or to win a lottery by which, every five years, one individual would be sacrificed and sent to Zalmoxis as a messenger from the world of the living.

The desire for the afterlife to be a place of eternal life, banqueting, feasting, and joyful things is reflected in the burial customs of the Thracian elite. Their monumental tombs took the form of underground chambers and passages, built from stones, bricks, or wood, and covered with soil to form imposing mounds. Often built on flat ground, these monuments could reach impressive heights—the largest non-royal tomb, the Shushmanets Mound, was more than 60 feet tall—and were visible across great distances.

Under the mounds, the tombs consisted of an antechamber where funerary offerings could be deposited. This area was also where horses were often sacrificed and interred to accompany their owner to the Afterlife. The antechamber connected to a burial chamber via a narrow passage. There, in the heart of the tombs, the deceased would be laid out on a couch or funerary bed. They would be dressed in their finest clothes or armor, and the burial chambers themselves were sometimes decorated with vibrant frescoes showing religious scenes, or with delicately carved stone sculptures.

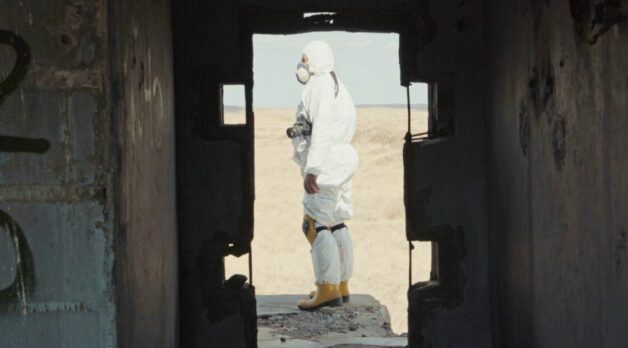

The builders of the monumental tomb of Seuthes III really went above and beyond. First, they selected an important religious site, a temple built near what is today the town of Kazanlak and what, in ancient times, was the main seat of Seuthes’ power, his capital of Seuthopolis. The temple had been in use for more than two centuries, but the builders repurposed it as a grave for their king.

The tomb, known today as the Goliama Kosmatka Mound, consists of a long entry corridor leading to a suite of anterooms that contained, as tradition dictated, a horse burial. The burial chamber was built from large stone blocks to resemble a colossal sarcophagus, and inside it was placed a model funerary bed upon which Seuthes’ body was laid.

The king did not go empty-handed to the afterlife. Far from it. His tomb contained a wealth of treasures, including the king’s helmet covered in gold leaf, his armor, sword, and spears. Wine amphorae were also placed in the tomb along with golden drinking cups and a silver-gilt scallop shell used to hold toiletries and perfumes that may have belonged to Seuthes’s queen, Berenike. Perhaps most stunning is the bronze portrait of the king with inlaid milky-white stone eyes that seem to stare fiercely back at the viewer.

Many Thracian treasures were looted from their tombs long ago, but by sheer luck, the tomb of Seuthes III remained unbothered. It was discovered by archaeologists in 2004, allowing its treasures to be recorded, photographed, and properly displayed in the National Archaeological Museum in Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia.

The Thracian cultures may be less famous than their Greek and Roman contemporaries, but the hundreds of monumental tombs dotted across the Balkans show very clearly that they were powerful, wealthy, and well-organized societies. Eventually, they—along with much of Europe—came under the control of Rome. While the independent Thracian power structures became reduced to client kingdoms of Rome, the Thracian people continued to occasionally trouble their new Roman masters with their fierce desire for independence. That desire was exemplified by arguably one of the most famous Thracians: The gladiator Spartacus, who sparked a rebellion that would lead to one of the largest slave uprisings in Roman history.

![Mother Nature Strikes Back in ‘The Feast’ [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/The-Feast.png)

![Director Haylie Duff’s ‘I Am Your Biggest Fan’ Is a Predictable But Watchable Kidnapping Thriller [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/I-am-Your-Biggest-Fan-2025.jpeg)

![Demo Available for ‘Besmirch’, a ‘FAITH’-Inspired Farming Sim Coming This October [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/besmirch.jpg)

![100K strategy and powering up with the right cards [Week in Review]](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/powering-up-credit-cards-1.jpg?#)

![2025 Best Credit Card Bonus Offers [May]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/credit-cards.jpg?#)