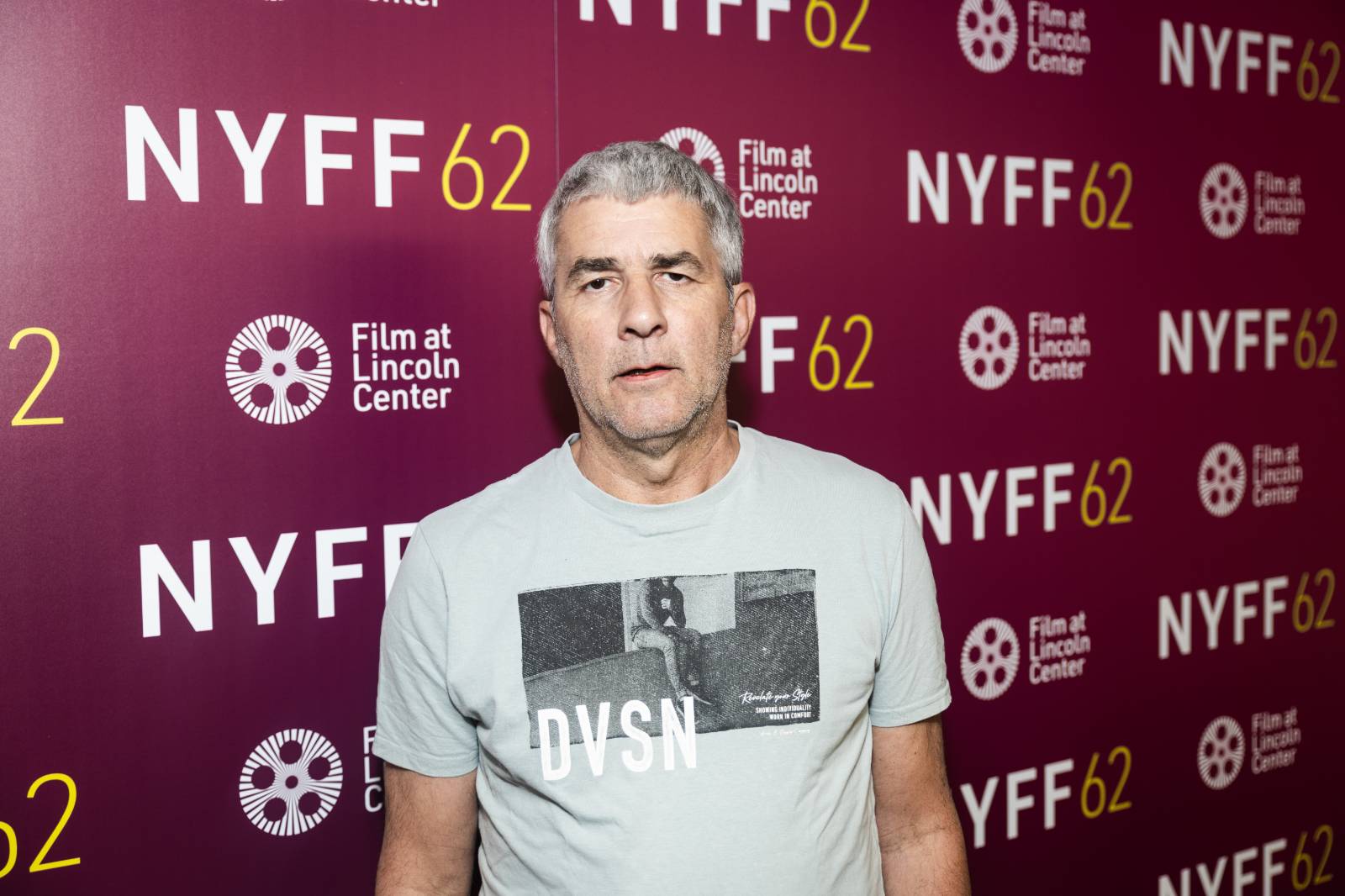

How Saba Connected With His Dream Producer No ID for ‘The Private Collection’

Saba details how he and legendary producer No ID connected for what's arguably going to be the rap album of the year with The Private Collection.

Fans of Saba have likely forged a connection with his music because of the way that he weaves spirituality and intention into his music. After earning early accolades in the mid-2000s as part of the budding indie Chicago rap scene, alongside artists like Chance The Rapper, Noname and Mick Jenkins, he independently released three albums — the aspirational Bucket List Project, the grief-stricken opus Care For Me, and the lineage studying Few Good Things — that were thematically and conceptually rich.

And so far, it’s hard to argue against his approach: He’s earned gold and platinum plaques for both his solo work (“Photosynthesis”) and collaborations (“Sacrifices,” alongside J. Cole and Smino for Dreamville’s Revenge of the Dreamers III compilation), he’s worked with some of the greatest ever and he’s moved from the Midwest to live in Los Angeles full-time.

But on From The Private Collection of Saba and No ID, he intentionally aimed to make a project that was less structured than his other solo albums. No ID earned much of his reputation in the ‘90s and ‘00s by making classics with fellow Chi-Town greats like Common and Ye, but over the last decade-plus, he earned a reputation for getting his collaborators to bare their souls — whether it’s Jay-Z opening up about infidelities and insecurities on 4:44, or Killer Mike coalescing bits from his childhood and southern heritage into his Grammy-winning album Michael.

Years after meeting the legendary producer for the first time, Saba planned to simply make a mixtape with him. He now refers to the final product as an album after switching his original batch of songs for new cuts, but he still made a point to keep the free spirit that he originally had in mind. The result is a self-described “tasting menu” of songs that find him ruminating on his career accomplishments, love, Black hair, and perhaps most notably, just how confident he is in his skills.

While sitting down at the Billboard offices in New York City in early January, Saba detailed the various familial and musical threads that led to him working with No ID, memorable studio sessions with the likes of Raphael Saadiq and Kelly Rowland, and how he decides to keep working on a record despite having songs in the can already.

“An album like this, I get to showcase my bag in a lot of ways, all these styles that I feel capable of,” Saba says. “You gotta be the most comfortable version of yourself, because that’s how you get the most confident version of yourself. I think that’s who I got to meet on this record.”

How did you and No ID meet?

We met in 2018, before I dropped my second album Care for Me. He flew me out for a meeting, with the intent on signing me. This is when he was at Capitol Records (as the label’s executive vice president). My dad has been doing music pretty much forever, and he knew him from the ‘90s. So my dad had been trying to connect us for a long time, but they fell out of touch. A friend of my dad had been putting the bug in the air, and eventually it made its way to No ID.

I didn’t end up signing to him, but we stayed in communication. When he was no longer with the label, it opened up the possibility of our working relationship. It didn’t have to be so by-the-book; we were able to get creative.

Before I moved out to LA, I was just going out there for meetings and trying to squeeze in a bunch of studio sessions. Our first time getting in the studio was in 2019. I had never worked with him, so I got to just see how he approaches his craft. He’s a talker, and then he backs up what he talks about. He’s like, “I’ll make 20 beats in one session.” He sat in the corner, he made 20 beats, gave them to me on the hard drive, and then left. I’m like, “Damn. I’ve never seen that done.”

And that’s the first time where we actually worked. I had been to the studio where I’ll pull up, and he’ll just chop it up with me. That’s one thing that is important: He gets to know the artists that he’s working with. I realized the value of that in his production style, because it’s for artists to tell a story. Down the line, when we actually started working on this project in 2022, those conversations were monumental. It sets the energy and the intent to do something amazing.

That reminds me of a story he told about working with Jay-Z on 4:44. He played the Hannah Williams sample for him from the title track, and as soon as Jay heard it, he’s basically like, “Oh, so we’re doing this now, huh?” It felt like they had kicked it enough to be able to communicate through a sample like that.

That’s 100, because it’s such a vulnerable process. Getting in the studio and sharing parts of your life in any any capacity is something that you gotta feel safe and protected enough to commit to. That producer/artist relationship transcends the studio. It’s another level of trust: When you get in the studio, you can access it without a second guess. You just go in there, fully you.

My understanding is that on your previous albums you had a very hands-on role in your production. Was that the same here, or did you trust No ID to do everything himself?

No ID gave me a lot of free reign to kind of treat this album how I make music, which I think was a big learning curve. I’m very hands-on when it comes to what I’m making. I like to change drum sounds, swap samples out; I like to produce, to be a part of the song. He would let me produce around some of his ideas, which was really cool.

It was something that I didn’t even think about asking, so maybe I stepped on some toes. But it was just my process, so I didn’t even think about it that way — like, “Damn, this motherf–ker gave me all of these beats, and I’m sitting here deconstructing them.” He sent over 100 ideas my way. So I’m taking parts that I thought were the best parts of these beats, and then some of them were just perfect already, where I didn’t have to touch nothing. It was a collaborative process, but it was also like a real trust-building process.

First you said that he made 20 beats when he was sitting with you that day. Then he just said that he gave you 100.

Yeah, so the 20 beats were in 2019. That was our first session, but we weren’t working on an album. Years down the line, when we reconnected once the deal had fallen through, the relationship had become something else. I ran into him when we were in Atlanta for (Dreamville Records’ 2019 compilation) Revenge of the Dreamers Vol 3. I was actually about to go do a deal, and by the end of our conversation, I didn’t want to do the deal. But he wasn’t talking me out of the deal; we were just talking about a new possibility, something that hadn’t been on the table yet. And I’m like, “Well that’s what I want to do.”

Pandemic happens, a lot of life is happening at the same time while all of this music s–t is happening. But right before I leave for the Few Good Things Tour, I’m visiting him at the studio. He’s like, “I made a hundred beats this week. How many of them do you want me to send you?” Being who I am, where I’m from, I don’t know when I’m gonna have an opportunity like that. So I’m like, “If you made a hundred beats, send me all 100.” Just to see what would happen. I didn’t expect him to, but he made a link and he put all 100 in there.

I was just treating it like homework: Here’s somebody who’s well established, well respected and a legend. And I’m from Chicago, so it’s a big deal to me that he trusted me with 100 beats. So I want to take it serious, even though I’m on tour. That was my first time we would turn every room into a studio, and we left that tour with 14 songs. The goal was to do a mixtape at first — but I’m getting back home and we hadn’t even gotten in the studio together yet. So I’m like, “I could drop [what I’ve already made], or I could really lock in.” My plan was to release it that year, but the music kept getting better. I’m like, “I guess I gotta just trust the process and see where this goes.”

You’ve reached the point in your career where you’ve been able to work with people that you respect on individual songs — Krazyie Bone, Black Thought, J. Cole. This is different though, locking in with No ID in an extended way. How much did you look up to him before you guys had worked together?

I mean he’s No ID, so you don’t fully know what he’s responsible for. When I think of what he did in the city, I think of Ye and Common, knowing the sonic texture of what they brought to hip-hop. It was always the North Star; the trajectory of what we were doing sonically was always inspired by the soul sample, the chops, the musicianship and the feeling of that music. Twista, Do Or Die, Crucial Conflict also, but that’s a big part of it.

And making the music, you don’t know what a motherf–ker like this is capable of until you see them in action. Being around him, he’s still working like he didn’t accomplish anything. He’s still calling me talking about (studio) plugins; he’s working like a 15-year-old producer or some s–t. Learning that and being around it, it’s really contagious. You want to give more, you want to do more, you want to do better.

You’ve shown a willingness before to record something and start an album over. You did that with Few Good Things, right?

Yeah, I had a similar plan for a Few Good Things. I originally wanted to follow Care for Me with a mixtape and just do 10 to 15 songs at the end of that year. I’ll go into a project with an idea of what I’m gonna make, but time has always been the greatest storyteller. So there’s always a matter of caution that I proceed with when it comes to identifying where the projects are; just because I had an intent doesn’t necessarily mean that I gotta marry myself to it.

That’s a benefit of how we’ve put out art in the past: the people who are really tapped in with us, they grow with the music. You don’t have to rush it, because they’ll spend time in the world that you create. So you might as well make sure it’s as detailed, lush, and vivid as possible. Looking at the chessboard, the s–t is completely different from when we originally started. It’s pieces falling off, it’s people dying. It’s all type of s–t that happened, where I’m like, “I gotta stand on all of the music that I’m making right now.” And it just led me to a new place.

What is it like to finish an album, and you hear it and it’s like, “Nah, let’s do something else?”

That just means it wasn’t finished to me. I never reached that moment of “The album is finished – let me do something else.” It’s more like, “It’s still in the oven. Let me swap that song out for a different one, or let me add something to that, because that’s missing an ingredient.” I think when I was looking at the mixtape version of it, it was a great mixtape. The goalpost didn’t move, I still wanted to have that energy where I get my s–t off and say whatever I gotta say. But I also wanted to have songs that I can stand on, live with, grow with. And I think the [presence of] songs is what really changed, that became a focus.

It feels like each of your albums before this has a very clear theme. Bucket List feels like “I’m right there, I’m on the cusp of popping.” Care for Me is about grief and loss. Few Good Things is about retracing your family history, and recognizing your role in that lineage. Do you think that this album has a theme?

I would say that this idea of The Private Collection is almost like snapshots; each song has its own texture. They all feel different, so I guess they’re only connected in the sense that it is a private collection. I think all of these songs are like small worlds of their own. That’s part of the mixtape nature of it; it’s an album now, but I didn’t want it to be like my other albums that are so concept-based. This one, the concept is just me and No ID having fun through the artform, showcasing how we hear hip-hop in 2025.

I don’t think I went into those other albums with the theme in mind. Over time, the projects reveal themselves to you. I don’t necessarily need a concept to start an album, but I do need a direction. I’m in the studio searching for a feeling; I’m not just looking to make good music. Good music is like, you rap good and the beat is good. But I think it’s so much good, that good is boring to me. Did it accomplish the feeling that you was looking for? Once that feeling happens, it’s like you’ve got the first pin on the map.

On “Acts 1.5” you said, “Every verse is a classic.” On “Westside Bound,” you said, “In’t a rap n—a that I idolize.” On “Woes of the World,” you were talking about wanting to go “toe to toe with the GOAT, because you’re second to none.” Was there a moment when you realized, “oh s–t, I really, I really feel this way”?

I’ve been popping s–t throughout my career, but most of my albums have been created from a moment of circumstance — these somewhat tragic events that happened in my life — and then I need to go to the studio and have my therapy session. It’s circumstance providing an inspiration, as opposed to, “Well, what if you just made what you wanted to make and said what you wanted to say?” My confidence has always been there throughout the other albums. But I think this one, it’s just having that mixtape start. The first versions of all of these songs were just go in the studio and rap well, have some fun, drop some bars. Songs like “Back In Office,” “hue_man nature,” songs from that first version of the tape, that was the intent behind them. Just the sport of it.

I’m always searching to make what only I can make, to say what only I could say. Some of that is in perspective, because I feel differently than how the next person might feel. If I can think of an interesting way to say how I feel, you can turn anything into a bar. But it’d be crazy to spend my life doing this and not be confident. It’s years of practice. I’m 30 years old, I’ve been rapping since I was nine. If I’m not confident by now…

I want to talk about a couple songs. “Every Painting Has a Price,” it seems like you’re talking about the evolving relationship between you and your listeners. How did that song come together?

“Every Painting Has a Price” is a title that was from my last album. It meant something different to me two, three years ago. I posted one of the early Few Good Things tracklists that had songs that didn’t make it, and a friend of mine was like, “‘Every Painting Has a Price’ is a crazy title.” I’m like, “D–n, I should reintroduce this concept into the next thing that I do.” That’s kind of where my idea to pocket things [comes from]; sometimes the idea’s gotta load.

Working on that record, that was the day Kelly Rowland was in the studio, so it was such a special moment. She came in to just ask No ID something, because she was in the studio next door. I had BJ the Chicago Kid there, (longtime collaborator/producer) Daoud was there, Eryn Allen Kane was there. Everybody was in that b–ch, just doing what they were there to do. The song happens, and Kelly pulls me to the side. We still don’t got the hook, we don’t got certain lyrics down yet. She’s asking me about the song, like, “What is this to you? What does it mean?” And it was crazy to have this heart-to-heart moment with somebody like her, and she’s extracting the song. For what became a few days, weeks down the line, I’m playing a song that used to be the outro, and Raphael Sadiq is like, “Make that the intro. Get that point across early.”

I feel like it is an update to my listeners, because they haven’t gotten a full body of work from me since 2022. So I think there’s a lot to update them on in terms of how my perspective has shifted where I’m at in life. I wanted to offer context before we get into all of the rest of the s–t that I’m gonna talk and what I’m gonna say. When I say “Every Painting Has a Price,” it’s very literal. The work, the craft, the amount of time, the dedication, the sacrifice that goes into all of this f–king work is often underappreciated. Because culturally, the value of music has shifted. So I don’t think people know what all goes into it sometimes. motherf–kers out here losing their mind, motherf–kers give everything that they have to it. Knowing that, I want to give people context before you hear where I’m at.

You said that “How to Impress God” was a song that you waited your whole life to make. What made that song that means so much to you?

“How to Impress God” was actually written pretty quickly. It wasn’t that deep, because my first version was just popping s–t. The first version is just, let me flex off all of my accomplishments. But then it’s like, “How do I add an extra layer to it?”

People see what we’re doing and base their lives off of that. I’ve done all of this stuff, and I just wanted to offer people perspective that sometimes, as an artist, it doesn’t really feel like much has changed. You still gotta do all of the self work, all of the mindfulness. You gotta really hold yourself down, because no external validation can offer that to you like you can. You can be the biggest artist in the world, but if you don’t handle this part of it, none of that s–t is gonna matter.

![Battle Hordes of Alien Horrors in Survival Shooter ‘Let Them Come: Onslaught’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/letthemcome.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)