Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: A Cure For the Ghosted

After a cruel break-up, a writer finds comfort and relief in Michel Gondry's offbeat 2004 romantic drama. The post Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: A Cure For the Ghosted appeared first on Little White Lies.

When my boyfriend ghosted me out of a two-year relationship, I blamed Michel Gondry. I know that it was unfair and inadmissible of me to pin it on a filmmaker I had never met, but if it wasn’t for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, I wouldn’t have had the recurring fantasy of erasing my ex from my memory. (Perhaps I was also desperate to scapegoat another Frenchman while my head was catching up with my heart in the aftermath of his disappearance.)

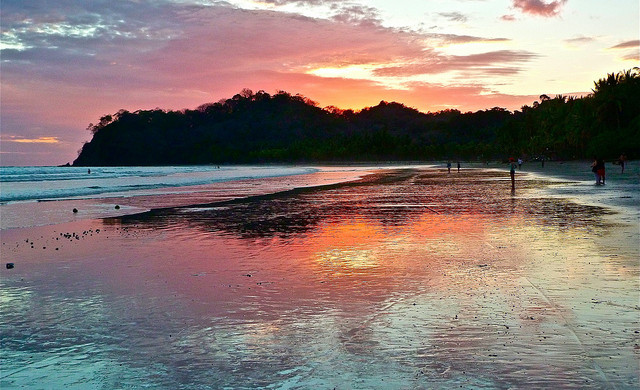

“Today is a holiday invented by greeting card companies to make people feel like crap,” declares Joel (Jim Carrey) in a voiceover at the beginning of Eternal Sunshine. His vendetta against Valentine’s Day seems perfectly reasonable, but there is a sour taste to his words, the whole monologue doused with bitterness and misdirected nostalgia. For a first-time viewer, the film’s opening sets a tone of melancholy as blue as the Montauk beach in wintertime, but if you are rewatching it – as I was, in the company of my 50 unanswered calls – you’ll more likely feel the nearby warmth emanating from a certain orange sweatshirt and the girl wearing it. Joel meets Clementine (Kate Winslet) then and there, for what they both think is the first time, but over the course of the film we learn that, in fact, they had been a couple for nearly two years until very recently.

It is on Valentine’s Day that Joel finds out that Clementine doesn’t remember him at all; what’s more, she had a procedure done to terminally remove all traces of their time together. What the medical company Lacuna Inc offers in Eternal Sunshine is a man-made miracle, using neuroplasticity and some software to relieve one of a loss (a relationship) by replacing it with another (memories). Given this paradox’s obvious appeal, it’s no wonder there’s an endless string of people lining up to use the service. Forget the pain, forget the source – what better selling point to help people get over their exes and move on? But the film makes it clear that such erasure is a deeply egoistic act, since it leaves the other partner to bear all the load alone.

While before, I would have empathised with Clem through and through (the hair colours, the volatility, the yapping), this time I felt every ounce of Joel’s pain. Being ghosted by the person I was planning to spend my life with felt like receiving an advisory Lacuna Inc card with the neat message: “X has had Y erased from their memory. Please never mention their relationship to them again. Thank you.” Gondry got the idea for such a card from conceptual artist Pierre Bismuth, and brought it to screenwriter Charlie Kaufman in 1998. It became the starting point of the script that would end up becoming Eternal Sunshine years later.

The two had already collaborated on the French director’s first feature, Human Nature, and Kafuman was a name thanks to his work on Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, so they shared a predilection for fantastical storytelling. While the procedure offered by Lacuna Inc goes beyond any kind of realism, the sci-fi element was never the real defining feature of Kaufman’s work in the first place. Nevertheless, when it comes to Gondry’s film, fantasy becomes a tool for Joel’s introspection rather than his wish-fulfilment. When Joel decided to wipe out Clementine just as she had erased him, I recognised in his childish resentment a thirst for justice that was as violent as it was disturbing.

Jim Carrey’s dimpled smile is perhaps the only thing one recognises from the actor’s comedic roles in Eternal Sunshine; here he is a muffled, monosyllabic shy man who opens up like a flower when Clementine’s around. No wonder the love story they share is in turn romantic, expansive, and explosive (thank you YouTuber therapist for a succinct analysis), but what elevated Eternal Sunshine to the point of audio-visual remedy in my eyes was how textured the object of affection was, regardless of whether it was Clementine or Joel’s memory version of her.

Winslet is effusive, quippy, and often infantile in her desire to connect; far from her “English rose” period drama typecast, she keeps Clem at a distance from the manic pixie dreamgirl archetype – even when she comes really close, as in the “Too many guys think I’m a concept” speech she gives towards the end. Even Joel himself is taken aback by the Clementine he remembers: a tangle of vulnerability and yearning tethered to a particular situation. In one memory, she shoots him a poisonous look over dinner; in another, their pillow talk makes him want to stop the procedure altogether.

As Joel’s vindictive screams – “I’m erasing you and I’m happy!” – signal a moment when one narrative layer (waking life) folds into another (dream, procedure, memories), we get a glimpse of what erasure looks like. Selfishly, I thought: This must be what it is like inside the mind of someone who would rather vanish without a trace instead of breaking up with you. Every time Clementine disappears from a scene as it unfolds, what’s traumatic about it is how seamless it is. Gondry and his team relied almost entirely on practical effects, with very little VFX and editing tricks. Yes, the occasional double exposure and fade transitions between two frames make Clem vanish, but the most memorable scenes were long takes with complex choreographies for Carrey, Winslet, and cinematographer Ellen Kuras. In-camera effects or something as simple as panning away to pan back when the character is gone, make Joel’s gradual loss of Clementine a tactile, bittersweet experience for the audience as well. For him, it became unbearable; for me, it was soothing.

Of course, it hurts to bear witness to this couple’s radical (yet non-consensual) break-up, but while Joel was there fighting tooth and nail to keep a memory of Clementine intact, I noticed my own animosity was fading. Perhaps a part of it will always nest in the deep shadows that were once the cloud-print pillow, between the aisles of Barnes and Noble (Clem’s workplace), or the frozen Charles River where Joel admits he was so happy he could “die right now.” The relationship between cinema and representation is never straightforward and simple, even when it feels liberating, but take it from me: the movie-magic of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind can make the ghosted come back to life.

The post Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind: A Cure For the Ghosted appeared first on Little White Lies.

![‘Yellowjackets’ Stars on Filming [SPOILER]’s ‘Heartbreaking’ Death in Episode 6 and Why It Needed to Happen That Way](https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Yellowjackts_306_CB_0809_1106_RT.jpg?#)

![‘Silent Hill f’ Announced for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series and PC; New Trailer and Details Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/silenthillf-1.jpg)

![‘The Astronaut’ Review: Kate Mara Is Trapped In A Sci-Fi Horror That Crashes to Earth [SXSW]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/13233357/the-astronaut-321845-kate-mara.jpg)

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.jpg)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)