What Kinds of Pasta Are There in India?

This article is adapted from the April 5, 2025, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here. “It's a very interesting question to ask, right? How do you define a pasta?” says Amay Borle, a chef based in Berlin, Germany. “Would you eat, in Italy, a pasta with bread?” “Italian-Americans would,” I reply, thinking of my own family dinners. “Italian-Americans would,” Amay agrees. “But not Italians, right? For Italians it’s the primo, and the second course would normally be meat. Italian-Americans kind of mash that together, making it one big meal. So I guess, first you have to think about what pasta is. And then, okay, from there, you're thinking about boiled dough dishes.” We’re sitting at the kitchen table in my boyfriend’s family home in Vienna, Austria, and I have just asked Amay his thoughts on Indian pasta. After meeting on Instagram through our mutual interest in food history, Amay and I have been friends for about two years. He knows more about food than practically anyone I know, especially the varied regional cuisines of India, where his family comes from, and he’s particularly knowledgeable about India’s “boiled dough dishes,” having made several of them himself. In 2023, a visit to the Himalayan region of Ladakh inspired Amay to make a video about a local dish called praapu. Derived from the cuisine of the Tibetan Muslim Balti people, praapu consists of small pieces of barley-flour dough pinched into a distinctive sail-backed shape, boiled, and served in a creamy green sauce, which Amay describes as “reminiscent of a Genoese pesto.” But instead of basil, the sauce for praapu is made from a mix of herbs and green chilies, and its creaminess comes from apricot kernels and their oil, which add a sweet cherry-almond flavor. As someone who loves learning about food and grew up eating a lot of pasta (both with and without bread), I’m always curious to compare different cuisines with my own frame of reference. Praapu certainly seems like pasta, but it’s connected to Tibetan cuisine, in which boiled dough dishes play a large role. What about in the rest of India? Modern Indians have adapted Italian pastas like penne to their own tastes. Masala pasta (masala being a general term for spices or seasoning) is a highly variable fusion dish that has become a staple of Indian street food and home cooking. And while masala pasta has a distinctly Indian flavor profile, there are also simple red, white, or pink sauce pastas that favor Western ingredients while being uniquely Indian in origin. “It's just looking at pasta as a boiled starch source,” says Amay. “And it reflects how you use a starch in your own different way.” Long before Italian pasta, fine vermicelli noodles arrived in India via Arab and Persian influence. In India today, these are widely used in both sweet and savory dishes, and, as in the Middle East, they’re usually fried or toasted dry before water is added. Some Indian preparations for vermicelli are adapted from native recipes, such as upma, a buttery breakfast porridge, which can be made with various starches including semolina or short noodles. Others are modifications of foreign dishes. Indians kept the name of the Persian iced noodle dessert faloodeh, but added milk and sometimes ice cream instead of the original sorbet. Then, there are the native Indian forms of boiled dough, like praapu, the ones that first sparked my interest. I was fascinated to discover that such dishes are found all over India, and, like Italian pastas, they take on a variety of shapes. Kadubu from the southern state of Karnataka resemble orecchiette. In the west, Maharashtran shengole are curled into rings or spirals, while Gujarati dhokli are cut into flat diamonds. “Normally the dough is flavored a lot,” says Amay of these dishes, another thing which sets them apart from Italian pasta. But it’s how they’re eaten that sets them apart the most. Some Indian boiled dough dishes are served as part of a platter with other sides and starches. This is especially the case for boiled dough made from chickpea flour, since it’s technically the protein component of a vegetarian meal, rather than the starch. In the northern state of Rajasthan, boiled chickpea dough balls called gatte are served in sauce and sometimes stuffed, ravioli-like, with cheese. But gatte “are considered a form of chickpea curry,” says Amay. “And I feel like, if you want to call that pasta, sure. If you want to call that dumpling, also, okay; but it’s eaten with something. It’s eaten with bread.” Perhaps this makes them more equivalent to a vegetarian meatball than a pasta? The more I try to impose my own categories or classifications onto Indian food, the more I realize that this is not a productive exercise. The best way to understand another cuisine is to approach it from within its original context, with an awareness of the culinary grammar rules that govern it. But questions like “What kinds of pasta a

This article is adapted from the April 5, 2025, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

“It's a very interesting question to ask, right? How do you define a pasta?” says Amay Borle, a chef based in Berlin, Germany. “Would you eat, in Italy, a pasta with bread?”

“Italian-Americans would,” I reply, thinking of my own family dinners.

“Italian-Americans would,” Amay agrees. “But not Italians, right? For Italians it’s the primo, and the second course would normally be meat. Italian-Americans kind of mash that together, making it one big meal. So I guess, first you have to think about what pasta is. And then, okay, from there, you're thinking about boiled dough dishes.”

We’re sitting at the kitchen table in my boyfriend’s family home in Vienna, Austria, and I have just asked Amay his thoughts on Indian pasta. After meeting on Instagram through our mutual interest in food history, Amay and I have been friends for about two years. He knows more about food than practically anyone I know, especially the varied regional cuisines of India, where his family comes from, and he’s particularly knowledgeable about India’s “boiled dough dishes,” having made several of them himself.

In 2023, a visit to the Himalayan region of Ladakh inspired Amay to make a video about a local dish called praapu. Derived from the cuisine of the Tibetan Muslim Balti people, praapu consists of small pieces of barley-flour dough pinched into a distinctive sail-backed shape, boiled, and served in a creamy green sauce, which Amay describes as “reminiscent of a Genoese pesto.” But instead of basil, the sauce for praapu is made from a mix of herbs and green chilies, and its creaminess comes from apricot kernels and their oil, which add a sweet cherry-almond flavor.

As someone who loves learning about food and grew up eating a lot of pasta (both with and without bread), I’m always curious to compare different cuisines with my own frame of reference. Praapu certainly seems like pasta, but it’s connected to Tibetan cuisine, in which boiled dough dishes play a large role. What about in the rest of India?

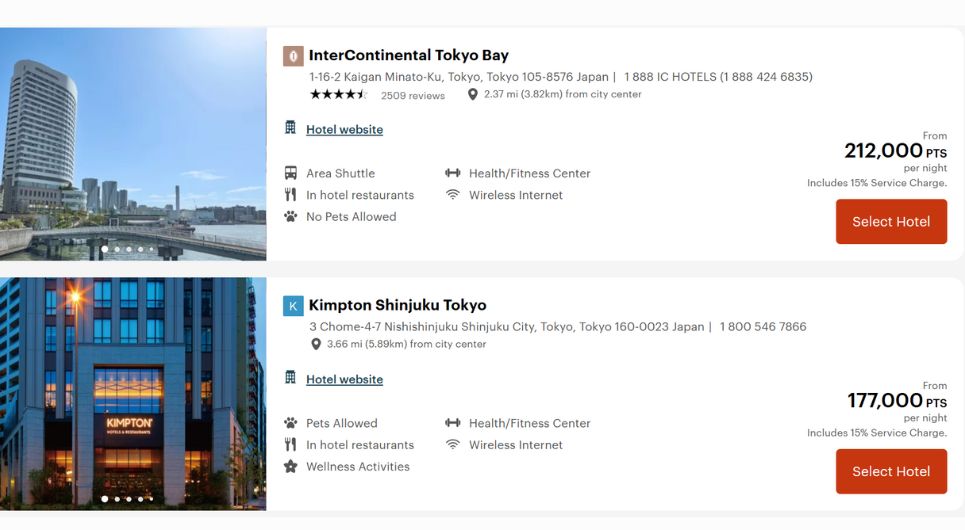

Modern Indians have adapted Italian pastas like penne to their own tastes. Masala pasta (masala being a general term for spices or seasoning) is a highly variable fusion dish that has become a staple of Indian street food and home cooking. And while masala pasta has a distinctly Indian flavor profile, there are also simple red, white, or pink sauce pastas that favor Western ingredients while being uniquely Indian in origin. “It's just looking at pasta as a boiled starch source,” says Amay. “And it reflects how you use a starch in your own different way.”

Long before Italian pasta, fine vermicelli noodles arrived in India via Arab and Persian influence. In India today, these are widely used in both sweet and savory dishes, and, as in the Middle East, they’re usually fried or toasted dry before water is added. Some Indian preparations for vermicelli are adapted from native recipes, such as upma, a buttery breakfast porridge, which can be made with various starches including semolina or short noodles. Others are modifications of foreign dishes. Indians kept the name of the Persian iced noodle dessert faloodeh, but added milk and sometimes ice cream instead of the original sorbet.

Then, there are the native Indian forms of boiled dough, like praapu, the ones that first sparked my interest. I was fascinated to discover that such dishes are found all over India, and, like Italian pastas, they take on a variety of shapes. Kadubu from the southern state of Karnataka resemble orecchiette. In the west, Maharashtran shengole are curled into rings or spirals, while Gujarati dhokli are cut into flat diamonds. “Normally the dough is flavored a lot,” says Amay of these dishes, another thing which sets them apart from Italian pasta. But it’s how they’re eaten that sets them apart the most.

Some Indian boiled dough dishes are served as part of a platter with other sides and starches. This is especially the case for boiled dough made from chickpea flour, since it’s technically the protein component of a vegetarian meal, rather than the starch. In the northern state of Rajasthan, boiled chickpea dough balls called gatte are served in sauce and sometimes stuffed, ravioli-like, with cheese. But gatte “are considered a form of chickpea curry,” says Amay. “And I feel like, if you want to call that pasta, sure. If you want to call that dumpling, also, okay; but it’s eaten with something. It’s eaten with bread.”

Perhaps this makes them more equivalent to a vegetarian meatball than a pasta? The more I try to impose my own categories or classifications onto Indian food, the more I realize that this is not a productive exercise. The best way to understand another cuisine is to approach it from within its original context, with an awareness of the culinary grammar rules that govern it. But questions like “What kinds of pasta are there in India?” can serve as a jumping-off point from which to explore a vast realm of culinary diversity.

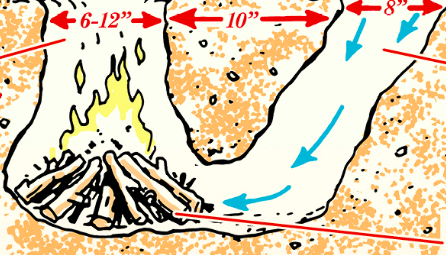

After all this talk about pasta and not-pasta, of course I wanted to cook something myself. So Amay sent me his mom’s recipe for a dish called namkeen jave, from the North Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Haryana. Jave are a slightly thicker cousin of vermicelli, and store-bought vermicelli may be substituted, but I really enjoyed the process of rolling, shaping, and drying them. This dish is traditionally eaten for breakfast, but makes for a hearty dinner as well.

![Isabelle Fuhrman Teases ‘Orphan 3’; “Wilder and Crazier” [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/first-kill-111.png)

![Declarations of Independents: The Masterpiece You Missed [DOOMED LOVE]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/doomed-love.jpg)

![A Delta One Server at LAX Handed Me a Laminated Venmo Tip Card—With the Airline’s Logo on It [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-one-lounge-lax.jpeg?#)

(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpeg?#)

.png?#)