The Dream Within the Fairy Tale: Emilie Blichfeldt on “The Ugly Stepsister”

An interview with the director of Shudder's latest fractured fairy tale.

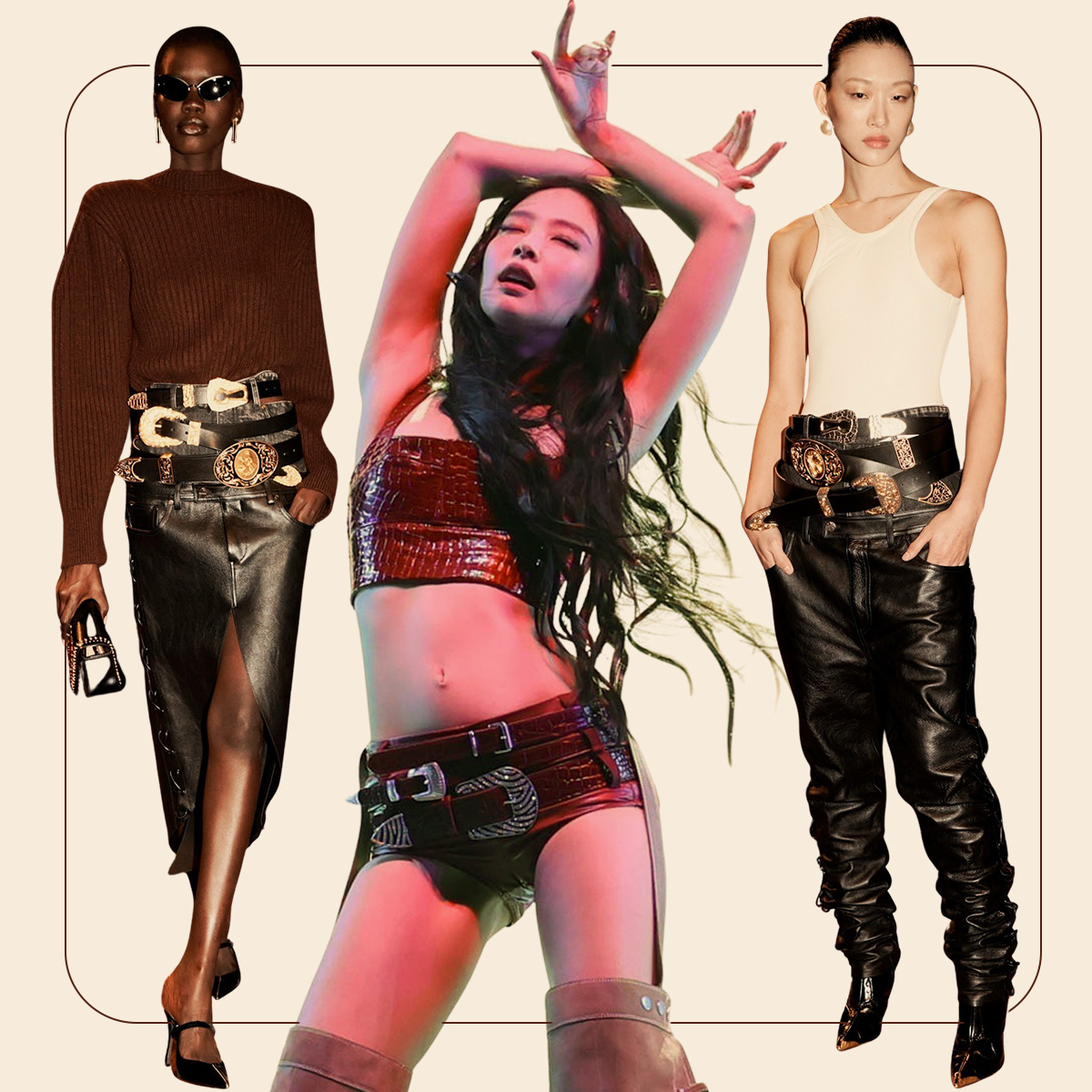

Thousands of versions of Cinderella exist throughout the world, but it’s safe to say that only one variant of the classic fairy tale features rotting flesh and maggots in place of a pumpkin carriage and mice, tapeworm diets and sewn-on eyelashes instead of magical makeovers, and a pivotal shift in perspective from the pure-hearted princess-to-be to her often-ignored stepsister, who’d do anything to win the prince’s affections.

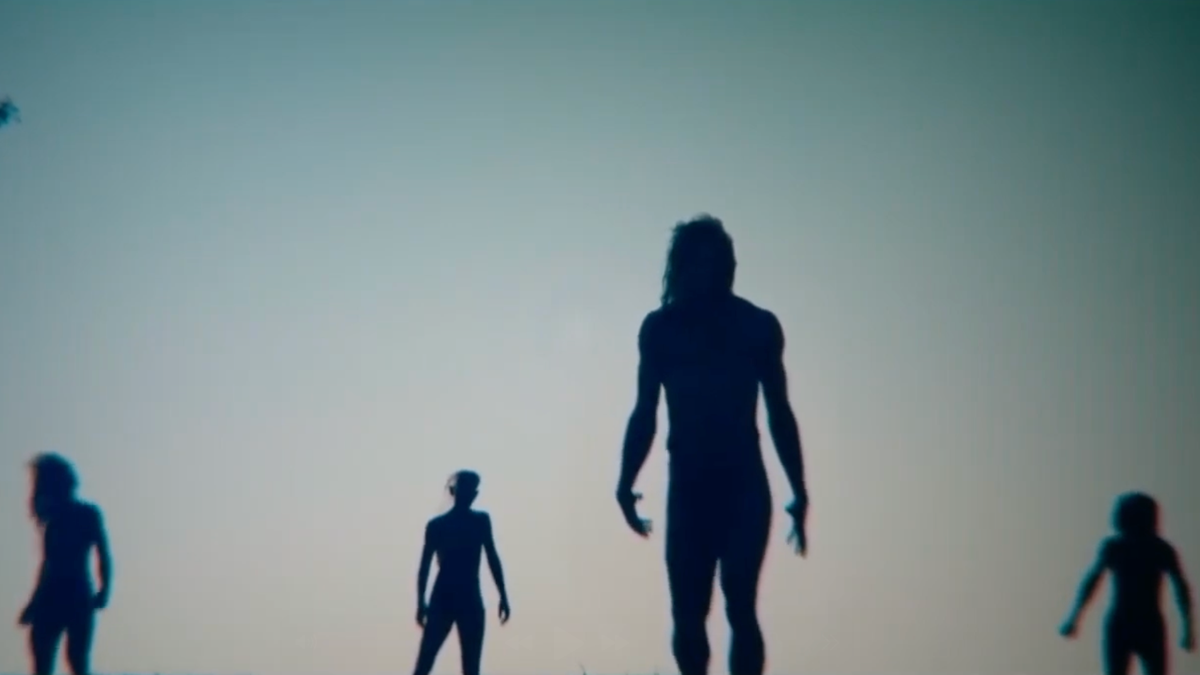

In “The Ugly Stepsister,” an impressively gruesome feature debut from Norwegian writer-director Emilie Blichfeldt (now in theaters), the titular character is Elvira (Lea Myren), the eldest child of a widowed schemer (Ane Dahl Torp) who’s determined to secure her social standing in the 18th-century kingdom of Swedlandia by marrying off her daughters—also including the more practically minded Alma (Flo Fagerli)—to wealthy suitors. Socially awkward but nevertheless dreaming of her happily-ever-after, Elvira harbors a crush on Prince Julian (Isac Calmroth), who will select his virginal bride at an upcoming ball.

With this occasion weeks away, Elvira can’t help but compare herself to new stepsister Agnes (Thea-Sofie Loch Næss), whom she sees as ethereally beautiful; what comes naturally to Agnes feels nearly impossible for Elvira. And so, at her mother’s behest, Elvira undergoes agonizing procedures by sadistic plastic surgeon Dr. Esthétique (Adam Lundgren)—for her teeth, nose, and eyes—before insecurities about her weight lead her to knowingly ingest a tapeworm. “You’re changing your outside to fit what you know is on the inside,” one tutor instructs her, though Elvira’s descent into delusion, starvation, and self-denial sets her unambiguously on a path to annihilation, not ascendance.

Blichfeldt cites not only the Brothers Grimm version of Cinderella, in which the stepsisters mutilate their feet to fit into the slipper, but also the films of David Cronenberg—particularly “Crash,” his flesh-and-metal psychodrama about car-crash fetishists—as inspirations on her satirical “beauty horror” retelling of the fairy tale. And although the film’s gross-out gore and shocking moments of bodily metamorphosis linger palpably in the imagination, “The Ugly Stepsister” grounds these brutally funny sequences in the tortured headspace of its protagonist, portrayed by Myren in a wild performance of contortive strength, daring, and poignancy.

Following its international premiere at Sundance and bow in Berlin, Blichfeldt’s film has been picking up steam on the genre-festival circuit, winning the feature film audience award at the Overlook Film Festival and director’s choice for best feature at the Boston Underground Film Festival last month. Ahead of the film’s U.S. theatrical release on April 18, via IFC Films and Shudder, Blichfeldt spoke with RogerEbert.com about the uncanny enchanted realism of ’70s fairy-tale cinema, the dangers of internalizing a destructive gaze,

This interview has been edited and condensed.

What version of the Cinderella story did you grow up on?

Well, first of all, [in Norway] it’s a tradition to watch this Czech film version, “Three Wishes for Cinderella” [also translated as “Three Chestnuts for Cinderella”], so all families there see it every Christmas Eve. And this is not like any movie you could see at Christmas, because it’s dubbed—and we don’t really dub movies in Norway, but it’s also not just normally dubbed, because it’s dubbed by this one guy who does all the voices, which makes it even more camp. And it’s already quite camp, but that gives it this extra camp layer. My parents didn’t believe in movies; they believed in books, so I grew up without a VHS or DVD player until I was 13. I didn’t have a relationship with the Disney version—only the Brothers Grimm and then this Czech version.

The visual aesthetic of Eastern European fairytale cinema from the 1960s and ’70s, like “Three Wishes for Cinderella,” is all over “The Ugly Stepsister.” I’ve seen you describe it as this atmosphere of “uncanny enchanted realism,” which is perfectly put. Personally, I associate that feeling with Shelley Duvall’s “Faerie Tale Theatre,” and what struck me in “The Ugly Stepsister” was the way this interplay between real and unreal—in music as well as visual style—reflects a balance between historical accuracy and something more modern and unexpected.

I had to make sure that it didn’t become a costume drama. I wanted to obscure the feeling that the film was made in, the feeling of 2025, so we sent it through the lens of the ’70s. It was our gaze, through the lens of the ’70s, upon the late 1800s, to create a timeless, once-upon-a-time feeling. And, for a long time, that also guided the soundtrack. I love Goblin and everything Argento, so I knew I wanted synthesizer realness, all crazy. Still, I was also looking at them less for the giallo horror of it all than for the dreaminess of their sound, and I found really nice ambient stuff from Harold Budd in the ’70s, and some Alice Coltrane from the ’70s that uses harp so beautifully. And that, for me, was this dream element; it was very linked to Elvira’s dream. There are these two layers in the movie: the fairy tale and then the dream. I wanted to distinguish those two and to feel the dream within the fairy tale. That’s where those two sounds came from, and they came up very early.

But, then, in editing, we had a screening, and I saw this first dream [play out] with cool, romantic, synthesizer music, and I was looking around the audience, and I was like, “That was so camp!” It was so ’70s that it went pastiche; it’s not the music in there now, which has a more modern touch. I was leaning so far into the ’70s that I felt like, “Do they understand that I know this is camp, too, and that I’m not just ’70s-obsessed?” The ’70s lens had obscured me a little too entirely; you couldn’t feel that there was a woman from 2025 behind all of this, who was aware of what she was doing. That had kind of disappeared, and we wanted to give it a little bit more of a modern feeling.

That’s when we found this great soundtrack from Vilde Tuv, a Norwegian composer and singer-songwriter, called “Melting Songs.” We used a lot of tracks from that EP; she’s more into the ’90s electronic sound, which is a bit harder and almost techno. When we put that on, suddenly, the humor found its place, because people could feel both that it’s very sincere in yearning, that music, but it’s also ironic, because it’s too much. That was where, when that music came on, the audience could be like, “Okay, I get how she feels, but I’m also on board that this is overboard. [laughs] This is too much, and it’s satire.”

To circle back to your gaze on the late 1800s, this was an exceptionally punishing time to be a woman in society. And you illustrate through “The Ugly Stepsister” the violence and self-hatred that stems from Elvira’s belief that she has to be this idealized version of herself to exist in the world. Can you talk a little about deciding that Elvira would internalize the violence of that gaze in such a visceral way?

It’s a great question. For me, it’s partially a personal story, because I’ve been self-objectifying and had internalized a confident gaze on myself that was very destructive for many years of my life. Luckily, I could get out of that, and the idea of what I wanted to make was simple. I wanted to make a story where people would sympathize, or at least empathize, and understand why someone would chop off her toes to fit the shoe. I wanted people to know what they’re doing, what they’re doing, and understand that emotion, where that comes from, because I could relate to being ready to do almost anything to try to fit within this appearance of an ideal.

When I created this character, it was all about, “But how do you get there?” Are you born with such a gaze on yourself that you think that you have to do this? Are you born with the idea that your body or appearance is where your value lies most? How does that happen? I think that’s something put on you, so how were you before that? I’ve been interested in this kind of transition, trying to make people understand how that happens. One thing is when people start telling you that you are not good enough, but then the other thing is the shift, when you start believing in that and doing it to yourself, as she does toward the end.

For me, the strongest image is the tapeworm, because when she takes the tapeworm and swallows it, that’s the first time she’s the perpetrator herself. It’s a “red pill, blue pill” moment for her. What reality do you choose? She chooses to internalize this gaze on herself and, in that, starts self-objectifying. This self-objectification then eats her up from the inside out, both physically and mentally. That’s such a strong image, because that’s what self-objectifying does to you. It erodes you from the inside, and it makes you a bit crazy. [laughs]

You start looking at your reflection in other people’s eyes. That’s what I wanted for Elvira, when she becomes the stepsister: she’s just looking at Cinderella. It’s not that Cinderella is doing something to her, or that she’s doing something to Cinderella; it’s just that she’s comparing herself constantly. It means she cannot empathize with Agnes because she’s self-obsessed.

Her getting help at the end to get [the tapeworm] out was very true. I wanted her to get it out, but she wouldn’t have the strength to do that herself. She wouldn’t be like, “Oh, I didn’t get the prince; let’s get the worm out.” That’s not how it happens. For me, there’s a deeper truth there that I didn’t know or see before I understood Alma needed to help her. Afterward, I was like, “Shit, that makes me emotional. If it hadn’t been for the people who had told me, “What you’re doing to yourself is not healthy; please, I will lend you my gaze to see the world differently, because how you’re seeing it is hurtful to you…” That is so important. And this is not something we can overcome by ourselves, although it feels like a personal, private thing to deal with. It’s a much bigger theme that we as a society must tackle together.

The tapeworm is grotesque and fascinating, Elvira intentionally ingesting this parasite that eats away at her from the inside. When it’s expelled, you also find this phallic resonance within the tapeworm, amplified by the last scene with the stepmother. Of all the medical procedures and beauty standards to invoke from the 1800s, when did the tapeworm come into this story?

It came in early. When constructing the outline, I researched different kinds of methods that had been tried in the history of time to see which ones I would put in. I’m a big body-horror fan, and what I love about body horror is that it always carries meaning or imagery, somehow, that’s bigger than just the gore itself.

I wanted to include [the tapeworm] because, for many women, trying to fit into this ideal is a lot about weight, but for a while, I couldn’t find where it fit. And I was like, “She takes it, she gets skinny, and she’s maybe sick,” but it wasn’t enough. It wasn’t satisfying enough that she had this thing in her; suddenly, I was like, “Oh my God. What comes in must come out.” [sinister laugh]

I saw the potential for that at the end of the story, and I hoped that it would be the most emotional moment, because there is some catharsis in her getting it out. There’s hope. It’s quite a bleak movie, but it was important for me that there’s some kind of hope toward the end. It’s bittersweet. She didn’t get what she wanted, and that was maybe okay. [laughs]

What were your biggest considerations when it came to casting Lea Myren in the lead role? Even without everything we’ve discussed, it’s an extraordinarily vulnerable, demanding part to play.

It was a very nerve-wracking process. What would this movie have been without a performance like Lea’s, to be honest?

It’s a very complex role for a young actress going through all those emotions, that physicality, and that change, both in looks and in manner. When it came to casting the stepsister, I had this idea, as long as she wasn’t a model or considered a great beauty or an ideal, that she could look like whatever. The casting was color-blind, for example. The only thing that she couldn’t be is naturally chubby, because I wouldn’t ask an actress to lose weight. I just wouldn’t do that, especially to a young one. And that was a sorrow, but that’s what I needed to do to tell the story.

We started casting, and I think we saw 500 girls, mostly quite young girls who didn’t have any experience. I was hoping to hit gold, but it didn’t happen. And then we started taking in older girls with more experience and one day, Lea came in. I was floored from the first audition. I was like, “Is this real?” I’d seen her in a really cool TV show called “Kids in Crime,” but I thought she’d been typecast for that role; in the audition, I got to see her as this full-fledged actor, doing all the things she can do. She was so funny, so endearing, so charming, so free to express herself with her marvelous face that can do so much.

And I think that’s the most beautiful paradox I’ve encountered with this filming, is how I needed to find someone who was the opposite of Elvira to play her. Lea grew up with a feminist mother, and she’s not self-objectifying; she’s not doing that. She’s so free to express herself through fashion, through her body, and that’s also what allows her to do this role—and to do it so magnificently, because she’s never looking at herself through the gaze of others and thinking, “Will they like me if I do this? What will people think if I look like that?” She’s just in the moment and doing it, which makes her such an incredible actor. She’s just a gift that keeps giving.

I just knew from the first audition: “Okay, that’s her.” She was on the floor for minutes in the second audition, crawling around like a lizard. Physically, it looks really good, and she’s telling me, “I did this for a whole day at the Lecoq school of physical theatre in Paris, okay? I’m so ready for all of this.” [laughs] I thought that was so cool.

On set, she wouldn’t stop screaming until I said cut. Sometimes, I thought she’d go down, and then I’d say cut, but she would just continue doing it. I found it fascinating how she was so entirely in it, and even experimenting on that journey of, “How does this evolve?” I had to hold back, not to take advantage of that, though I did sometimes, because it was so cool, and it ended up in the movie every time.

There were hard, long days, and I put her through a lot. Suddenly, one day, after she had done the first and second part of the stunt of Elvira falling down the stairs, I found her crying outside, and I thought, “Oh, no. Now, she’s broken—my strong girl, I pushed her to the limit.” But then I went over to her and asked if she was okay, and she said, crying, “Yeah, it’s not me. It’s Elvira. It’s just so hard for Elvira.” I was like, “Oh, this is insane. She’s so cool.”

She’s highly committed. It’s those reactions that give the film its most blood-curdling moments. I’m curious how you build a performance like that, to provide that sense of an emotional and psychological trajectory, in a fairy-tale atmosphere.

We just decided to let Elvira go, somehow. Lea is an actress who can go big. And I told her, “You should feel no shame in that, because that means you have range. And so, whenever I tell you to rein it in, it’s never because going big is bad. It’s just that, for this moment, we need to.”

She’s told me that that made her feel very safe, that she could never do wrong. A lot of actors who have that in them can feel they’re overacting; some directors, I know, can be hard on them for that, but I just wanted to give her love for that, especially for this movie. It was all about finding people who wanted to play.

It’s a fairy tale, and I didn’t want it to end up like a psychological drama or a period piece. It was not my idea when [Adam Lundgren, who played Dr. Esthétique,] came to audition and spoke in this pretentious, almost-French Swedish. I was a bit like, “Is that taking it too far?” And then, in costume rehearsal, he did it again, and I was just so endeared by it. And I was like, “Let’s go. Let’s not hold back. Let’s go big or go home and have fun doing it.”

Lea and I call Elvira our “love child.” We were very pressured for time on set, but it took just a few days before Lea and I needed only to look at each other, and we knew. I almost didn’t give her direction. At the wrap party. I was like, “Are you fine? Have I given you enough attention?” I was giving so much attention to so many other things, because I knew I could trust her. And she said, “Yes, I understood that. I felt you were there for me when I needed you, but it was also a great experience to be set free in that way and not over-directed.” Total love child, yes.

This is a film of grotesque images and strong ideas. What was the trickiest stunt to pull off in “The Ugly Stepsister,” whether conceptualizing it within the story or executing it on set?

In terms of the stunts, that moment on the stairs was definitely the biggest stunt for the stuntwoman who doubled for Lea, and it was horrible for me. They were like, “Do you want us to do it again?” And I was like, “Is she safe? Can she do it? I don’t know if I want to ask for another one; what if she gets hurt?” But she was so cool doing it, you know? And the last shot we got there, where she’s falling down the stairs, so cool, was written like that; it was written that she would break her nose at the bottom.

I had to be quite specific about it. I love that, though, when you get the pros on set and are confronted with your idea, you have to be specific about it, because that’s when you start making the story. [Marcel Zyskind,] my cinematographer, got in the mix because, in the script, she cracks her nose when she hits the wall, then she tumbles down. And he was like, “She should break it at the end of the staircase.” And I was like, “No, she should do it there, at the wall.” And he was like, “Does she have to?” I said it had to do with rhythm. But at the end, after he’d agreed with that, we got the shot with Lea, and he asked, “Can we do just one take where she breaks it there?” In editing, we found out I was right about rhythm, and he was right about where she should break it. [laughs]

Last question. You’ve cited David Cronenberg’s “Crash,” which you saw while studying in film school, as a film that opened your mind to horror as a genre that could allow you to explore the body and the mind in the ways you do in “The Ugly Stepsister.” Your film is in theaters this Friday, and so is “The Shrouds,” his latest…

I’ll tell you a secret story: I was invited, to my surprise, to the Criterion Closet, to pick out some movies when I was in New York, and have my photograph taken. I felt honored. Very random, but so cool. I came back two days later—also to my surprise, because I became friends with Sean Price Williams, who sees films there sometimes, so he invited me to go—and someone told me that David Cronenberg would be there two days later. I thought, “How cool would it be to use the Criterion Closet as a post-box between filmmakers?” So, I wrote a little Post-It note, just a little greeting for him, and stuck it to my picture, in case he sees it.

If you go to a cabin in the woods, there’s a book to sign, usually, right? The Criterion Closet should have a cabin book so that filmmakers can write greetings to each other. And the staff can be like, “Mr. Cronenberg, you’ve received 15 greetings since the last time you were here.” Wouldn’t that be great?

They should sincerely take you up on this.

Filmmakers talking to each other. That’s what we do with the films, but it would feel so much cooler, actually, to do it with that intention.

“The Ugly Stepsister” opens in theaters April 18, via IFC Films and Shudder.

![You'll Probably Never Guess What Live Musical Performance Blew This Sinners Star Away [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/youll-probably-never-guess-what-live-musical-performance-left-a-mark-on-this-sinners-star/l-intro-1745021921.jpg?#)

![It’s Unfair to Pay 100% for 50% of a Seat—Why Airlines Must Start Refunding Customers When They Fail To Deliver [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/broken-american-airlines-seat.jpeg?#)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)