How Much Is a Hit Song Worth Today v. 1999? It’s Complicated

Streaming has helped the music industry generate more money than at any point since 1999, but hit songs used to drive album sales.

Whether it was Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” LiAngelo Ball’s “Tweaker,” or the six songs at the heart of Drake and Kendrick Lamar’s epic rap battle last year, Billboard has recently spent a lot of time reporting on how much money a hit song generates.

For a look back at our coverage, we estimated how much the top 10 songs of 2024 earned, what GELO’s locker room anthem has netted, and the millions made from Drake and Lamar’s diss tracks.

These stories sparked questions from readers, including one that came up repeatedly: Does a hit song today make more money than a hit did before streaming took off?

We asked this question of roughly a dozen music economists, entertainment industry bankers, and record label and streaming company executives, and they largely agreed that streaming has increased the long-term value of a hit song. However, hit songs used to drive album sales, which may have been more lucrative upfront.

It is difficult to directly compare the value of a hit song in 2024 to a hit song in 1999 — the year that record industry revenue peaked in the modern era — because the business largely moved away from issuing singles by the late 1990s. To hear a hit song, then, a fan would buy an album for as much as $18.98.

In 1999, when albums were the dominant configuration for music, 88 albums sold more than 1 million units in the U.S., according to Billboard. Albums often sold for more than their wholesale price of $12, which could mean certain older hits had a greater upfront value. However, the sources Billboard spoke with for this story all agreed that after a fan owned an album, they had little incentive to pay for that particular music again — so after about 12-18 months, the album would stop making much money.

In contrast, streaming keeps all music closer to fans’ fingertips, and hits tend to continue making money over a longer period, as opposed to a brief hype window in the album sales era.

One longtime record label executive who asked to remain anonymous estimated that a gold record in 1999 generated more than $6 million in sales, based on a wholesale price of around $12. Adjusted for inflation, that’s the equivalent of $11.3 million in 2024 dollars, according to the U.S. Federal Reserve.

In 2024, the biggest hit was Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” and Billboard estimated it generated $10.7 million from U.S. audio, video and programmed streams, digital downloads, and radio airplay spins. But due to streaming’s long tail, which has helped keep “A Bar Song” in the top five of the Billboard Hot 100, the track has continued earning significant streams in 2025: more than 140 million on-demand audio and video streams, or $192,000 in additional streaming revenue, just this year.

“[Back then], after a huge spike in revenue, a hit would have decayed over time by 60%, 70%, 80%, and eventually the song would drop to a much lower base,” says Concord CEO Bob Valentine. “Now in the streaming world, a song comes out, you get the huge pop from consumption and revenue, and because of the way algorithms keep a song in playlists and rotation, the song is much stickier. It has a higher base.”

Valentine says this is why companies like his have been able to persuade outside investors that music royalties can be securitized and sold to institutional investors like insurance companies. Concord has become the music industry’s model for raising money from such asset backed securitizations (ABS), having raised more than $5 billion to date.

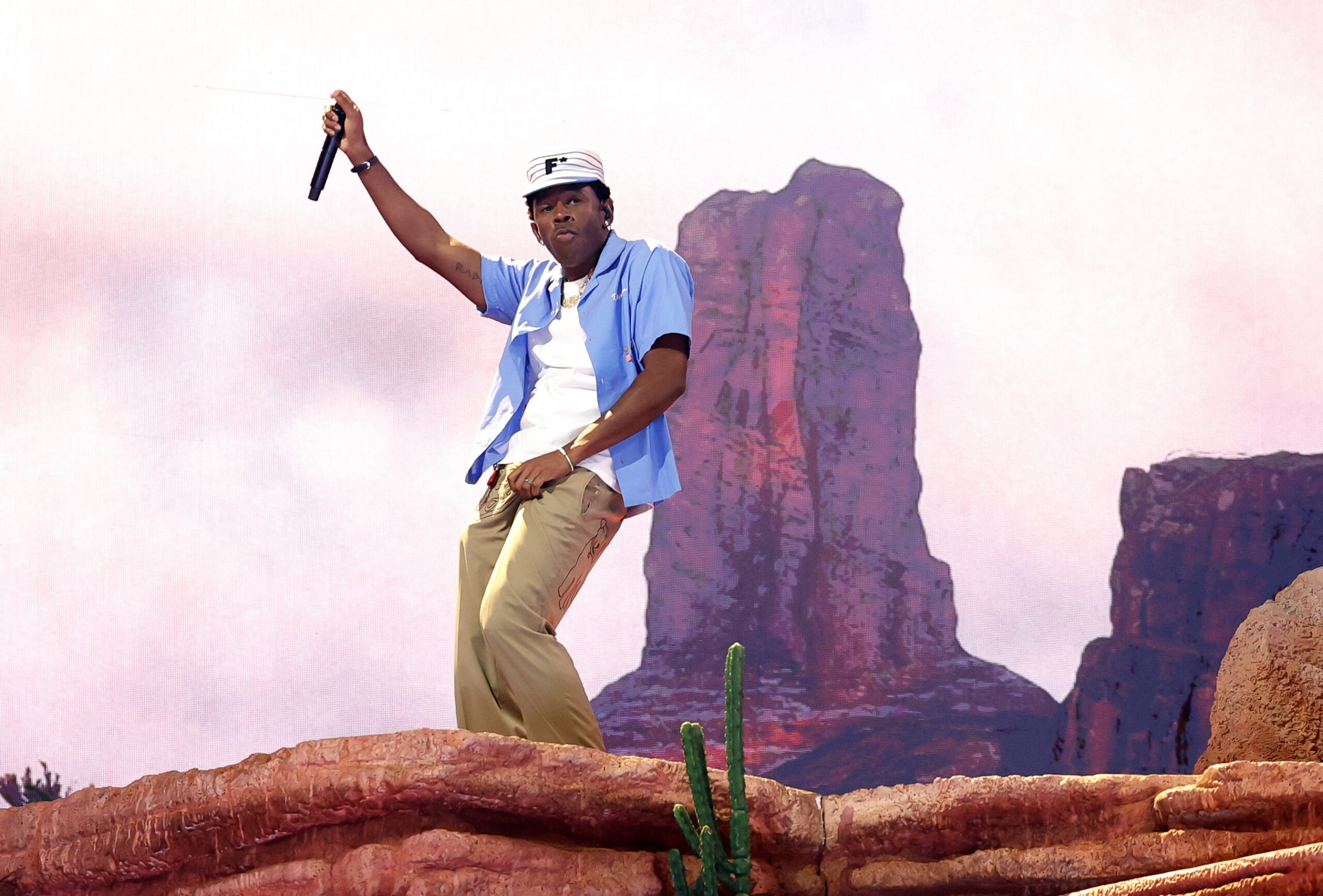

While Concord is known for owning famous catalogs from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, it scored a top 10 hit in 2024 with Tommy Richman’s “Million Dollar Baby,” which Billboard estimates generated around $7.4 million.

If Concord’s catalogs are like bonds — generating consistent revenue that can be relied on for decades — hits are more like venture capital. After an initial investment, a hit can present substantial upside, Valentine says. Concord is now comfortably the fourth or fifth largest music company thanks to the strength of its publishing division and catalog, so it can afford to take risks to get more hits, which is why it’s pushing to develop its front-line business to release more songs like “Million Dollar Baby.”

The music industry globally made $41.3 billion in 2023, according to the most recent data from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and the Confédération Internationale des Sociétés d´Auteurs et Compositeurs (CISAC).

The IFPI, which reports figures on an absolute dollar basis, not adjusted for inflation, says global recorded music revenues are at their highest level since it began tracking them in 1999.

Several sources interviewed for this story noted that, despite record-high revenues in the music industry, not everyone who contributes to making or performing a hit song makes more money today, and that many songwriters may have made more money in 1999.

For one thing, the number of songwriters credited on a hit song has increased significantly in the last decade, according to an analysis by Chris Dalla Riva in 2023. Dalla Riva found that the average number of songwriters per Hot 100 No. 1 hit rose from 1.8 during the 1970s to 5.3 in the 2010s. He noted that with interpolations, many songs credit far more songwriters: For example, Beyoncé’s Renaissance song “Alien Superstar” listed 24 songwriters.

“There is more money, we can all agree, but there are way more mouths to feed,” former Spotify chief economist and author Will Page said in an interview with the BBC in January.

Songwriters don’t just make less money because more of them work on major hits; they also make less because of the way streaming changed payouts, sources say. When the industry revolved around album sales, a songwriter on a less popular song earned the same as a songwriter on the album’s most popular song.

The rising tide effect no longer applies today because fans stream songs on a mostly a la carte basis.

Additional reporting was contributed by Ed Christman.

![Battle Hordes of Alien Horrors in Survival Shooter ‘Let Them Come: Onslaught’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/letthemcome.jpg)

![Please Watch Carefully [THE HEART OF THE WORLD]](http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/the-heart-of-the-world-5-300x166.jpg)

![Passenger Pops Open Champagne Mid-Flight—That Didn’t Go Over Quietly [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/passenger-pops-champagne.jpg?#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven Bours](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube-1.png)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)