A Desert Review: Neo-Noir Debut Can Only Coast on Vibes For So Long

Anything weird, offbeat, or psychosexual seems to elicit the world “Lynchian” in descriptions, reviews, or marketing material. It’s become a shorthand and ultimately a reduction––more than of an influential filmmaker, a style that pushes against norms of narrative storytelling. Something that is Lynchian is also, by extension, a little beguiling and hard to pin down. […] The post A Desert Review: Neo-Noir Debut Can Only Coast on Vibes For So Long first appeared on The Film Stage.

Anything weird, offbeat, or psychosexual seems to elicit the world “Lynchian” in descriptions, reviews, or marketing material. It’s become a shorthand and ultimately a reduction––more than of an influential filmmaker, a style that pushes against norms of narrative storytelling. Something that is Lynchian is also, by extension, a little beguiling and hard to pin down.

Expect people to describe Joshua Erkman’s feature debut A Desert as such. On the surface, it fits all criteria. Not only does the narrative concern itself with middle and rural America; it’s also preoccupied with an Oz-like journey and––finally doubling back on itself, in snake-like fashion––lands on an ending that can best be described as opaque, at worst nonsensical.

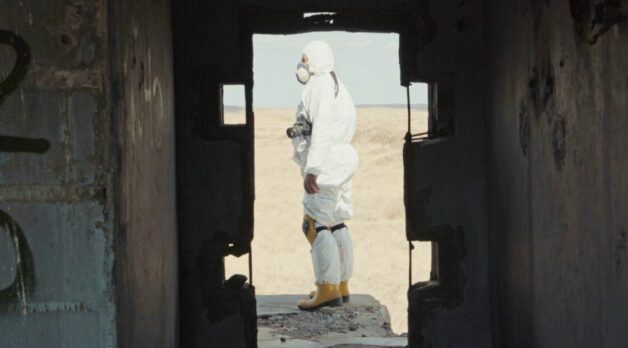

While the ending––a weird collage that attempts to recontextualize the story that came before it––will probably be the main talking point, it’s also the least-interesting component of Erkman’s feature. Instead, it’s the bifurcated structure that lends itself to a compelling, albeit frustrating narrative. At first the film is about washed-up photographer Alex (Kai Lennox) traveling through the fly-over states in an attempt to revisit his most commercially successful work. Shedding his phone and relying on strangers to guide him, he photographs the rust belt with an antique camera, documenting the dilapidation and decay of the American West, a theme that put him on the map too many years ago to count.

A chance encounter at a seedy motel with Renny (Zachary Ray Sherman) and Susie Q (Ashley B. Smith), who claim to be brother and sister but are more likely a pimp and prostitute, abruptly ends his story. After complaining that they’re being too loud, Alex nevertheless invites them into his room for a portrait and to party. The experience has Alex fall back on the hedonistic tendencies he’d pushed down long ago.

While we know what happens to Alex when he goes missing––a choice that takes the air out the story somewhat––his wife Sam (Sarah Lind) does not. From there A Desert switches to the private detective Harold (David Yow) she hires to track him down. Washed-up in a different way, Harold has a cynical worldview to inform his investigation. He’s at home in the motels and abandoned buildings that Alex fetishized with his camera, and his search is ultimately less-interesting than the film’s other thread. Erkmann uses these two men as foils, juxtaposing how they navigate the world––one with an outsider’s eye that only sees the decaying towns as an aesthetic object, the other someone who sees the darkness in humanity everywhere he turns.

That’s all well and good, but doesn’t exactly make for the most propulsive narrative. We know what happened to Alex, and the mysteries surrounding why ultimately aren’t a strong-enough hook. Though occasional flashes to a dark room of monitors showing grungy porn foreshadow the weird nightmarish descent that Harold and Sam go through at the end, it’s all in service of a mood rather than some coherent viewpoint.

This isn’t helped by the fact that Alex and Harold make some awfully dumb decisions throughout. While A Desert is being described as somewhat horror-adjacent, it’s more the characters’ baffling choices than actual story that seem informed by genre. Alex inviting Renny and Susie Q into his room, only to drink their weird liquor, is the type of decision that leads to one screaming at the screen; that he continues allowing Renny to take him deeper into the desert in hopes of finding more objects to photograph is even more confounding. The same goes for Harold’s decision to party with Susie Q when her entire persona gives I’m-going-to-drug-you energy. One imagines a former cop, even so washed-up as Harold, would know better.

It’s obvious that Erkman is striving to emulate Lost Highway. And, to a certain extent, he excels at creating a simulacrum, coasting on vibes, narrative teases at a larger meaning, and hazy, neon-lit cinematography. Yet once the style settles in, we are left with a compelling but frustratingly ambiguous film.

A Desert is now in limited release.

The post A Desert Review: Neo-Noir Debut Can Only Coast on Vibes For So Long first appeared on The Film Stage.

![‘Omukade’ Trailer – Thai Monster Movie Unleashes an Insane Giant Centipede Nightmare! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-30.jpg?fit=1713%2C931&ssl=1)

![‘Sally’ Trailer: Acclaimed Sundance Doc About Trailblazing First Woman To Blast Into Space [Ned]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/02065833/unnamed-2025-05-02T065720.586.jpg)