Why the Dire Wolf Returned and How It Could Save the Red Wolf

The first time one hears that scientists have brought back the dire wolf can be a little surreal. While this apex predator of the Ice Age, a North American legend hailing from the Pleistocene epoch, is believed to have breathed its last 10,000 years ago, it now walks the Earth again—or at least a pretty […] The post Why the Dire Wolf Returned and How It Could Save the Red Wolf appeared first on Den of Geek.

The first time one hears that scientists have brought back the dire wolf can be a little surreal. While this apex predator of the Ice Age, a North American legend hailing from the Pleistocene epoch, is believed to have breathed its last 10,000 years ago, it now walks the Earth again—or at least a pretty uncanny approximation of it courtesy of American biotech company Colossal Biosciences. The same firm which made the internet fall in love with woolly mice just a month ago has now lived up to its “de-extinction” mission statement; it has replicated the genome of a prehistoric creature in a living animal.

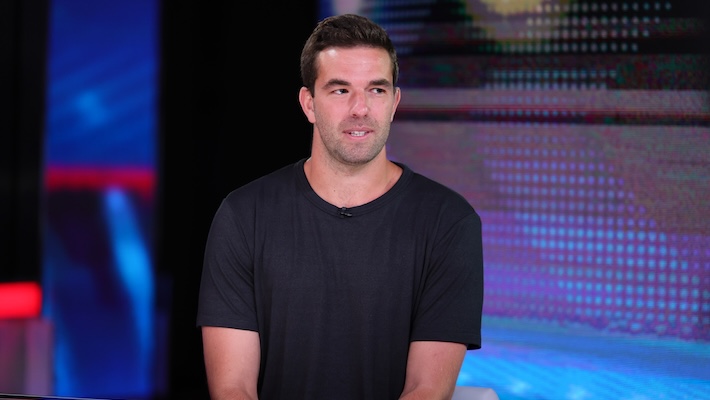

At this point, Jurassic Park comparisons start appearing passé. Nonetheless, when we catch up with Colossal CEO Ben Lamm, he allows himself to smile at the similarities between the news and that famous scene where Richard Attenborough tells Sam Neill they have a T-Rex.

“I think my John Hammond answer is I have three,” Lamm grins in reference to the trio of dire wolves Colossal has so far created: brothers Romulus and Remus, both about five months old, and little Khaleesi, who is just six weeks old as of press time. If it seems a tad audacious to welcome comparisons to a Hollywood movie, it is only because this is a moment bathed in audacity—and perhaps an opportunity for conservationists. As Lamm admits, two years ago they had no plans to resurrect the dire wolf, yet 18 months after asking themselves if they could, Romulus and Remus roared into the world. And soon enough, Colossal hopes to have seven or eight such dire wolves living on a 2,000-acre preserve in the northern U.S.

It’s a remarkable achievement, and one with applications that extend far beyond a genetically-engineered wolf pack.

Why the Dire Wolf?

Founded in 2021 by Lamm and Harvard geneticist George Church, Colossal has raised immense capital in under half a decade by operating on the ethos that de-extinction and modern wildlife preservation are intrinsically linked. They’ve also made headlines via the applications of their research into bringing back the woolly mammoth (a dream they still aim to realize by 2028), such as when Colossal led breakthroughs in combatting herpes in baby elephants.

Yet the dire wolf, which was made famous in popular culture because of fantasies like Game of Thrones, was not originally on Colossal’s radar. Nor for that matter was the current plight of the red wolf.

“We were working with some of our Indigenous partners in North Dakota, and we were giving an update on our bison population genomics map that we’ve been building [to bring back] a genetic diversity that’s been lost in the bison,” Lamm explains. After the presentation, the biotechnology leader took a meeting with Mark N. Fox, the chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes (also known as the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, or MHA Nation). While helping guide a tour through their cultural center, Fox raised a salient point: why is Colossal focused solely on extinct species from different parts of the world like the Tasmanian tiger or the woolly mammoth—which while also in North America tended to roam almost everywhere during the ice age.

“He said I just don’t understand why you’re not working more on American horses and American wolves,” Lamm remembers. “When you’re an American company, your first animal should be solely [American].” He also began telling Lamm about something Indigenous people call the great wolf. “He said it was a much larger wolf, it was a stronger wolf, it was white.” And based on how long the people of the MHA Nation have been on this land, Fox said he thought it was a Pleistocene wolf. The dire wolf.

The dire wolf is indeed believed to have mostly resided in North America between 125,000 and roughly 10,000 years ago. Furthermore, over 90 percent of their fossils have been discovered in what is modern-day U.S. territory—which takes on a bitter sense of irony when considering one of their modern lupine relatives currently on the brink of extinction in this country.

“Three months later I was in North Carolina about a completely different topic, it had nothing to do with red wolves, but the Red Wolf Recovery Program came up,” Lamm says. “They talked about how they’ve been working for 40 years and are just not really making progress.” Since the red wolf was reintroduced into the North Carolina wild, it is believed that only 17 of these animals still roam free.

“It dawned on me that the most endangered wolf in the world is this American wolf,” Lamm says. “When we think about America, you think about the bison and the wolves, and bears eating out of streams and bald eagles. And you’re telling me that we can’t save our own wolf?”

Yet by the same time Lamm was having these fateful discussions, his company’s whole-system approach for innovating in the gene-editing and CRISPR space—with Colossal handling computational analysis, embryology, genetic engineering, and even staffing an artificial womb team under one proverbial roof—had yielded positive results. Beyond raising capital and earning major Hollywood investors like Peter Jackson, the company was also seeing breakthroughs in working with edited cells.

“This is super sci-fi-ish,” Lamm prefaces, “but we had petri dishes growing mammoth hair organoids. We’ve engineered mammoth hair, so we know [the process] works… but it’s not a full complete system of an animal.” In this way, the woolly mouse was intended to be a proof of concept for the company’s aspirations. But when it came time to huddle around a whiteboard and decide what ancient animal they could actually de-extinct, the dire wolf suddenly began looking extremely attractive.

“If we do try the dire wolf, we could probably develop technologies that will have an application for conservation,” Lamm says in reference to the red wolf. “We can work with the Indigenous people groups that are excited about it; it could be a symbol of American pride; it just kind of all came together, and then the project went so much faster than we thought.”

All told, from that meeting to Romulus and Remus’ birth, a mere 18 months passed, with the project nearly beating the woolly mice into existence. Says Lamm, “Eighteen months for something that’s been gone for 12,000 years.”

Lessons Learned by Romulus and Remus

As of press time, the dire wolves called Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi are far from full-grown. Khaleesi is still a puppy, and Romulus and Remus are maybe only a third full-grown with modern gray wolves taking between 14 and 18 months to reach full maturity. Yet already, these white-haired creatures are taller than the gray wolf. Soon the dire wolves will be heavier too.

“They are insanely strong,” says Lamm. “They’re already 80 pounds. Most wolves are 75 to 100 pounds, and some could be up to 110 pounds if they just killed an elk. But without these being full, they’re over 80 pounds and they’re five months old… so we think they’re going to be 140 to 150 pounds. Some people even say they look like little ponies at this stage.”

Some of the results of their appearance is unsurprising to scientists, especially after Colossal reconstructed a dire wolf genome by extracting DNA from a 13,000-year-old fossilized tooth, found in Sheridan Pitt, Ohio, and several pieces of a dire wolf’s inner ear found in American Falls, Idaho (the ear is believed to date back to around 72,000 years ago). For instance, there was almost never any doubt that unlike the mythical “direwolves” on Game of Thrones, the real things would be exclusively white.

“There’s about 50,000 years of genetic divergence between our two samples, and they’re not regionally found, they’re separated,” Lamm explains. “So we do believe dire wolves were all white.”

Other features, however, could be learned only by birthing Romulus and Remus and watching them grow.

“They have a longer tail [than gray wolves],” Lamm points out, “and while they’re not related to foxes, it’s thicker and almost more fox-like. They’re truly beautiful.” Most striking of all, though, might be the white mane that the fossil records could never reveal.

“We didn’t know that they had that,” Lamm notes. “We knew they were white, and we identified what genes drove their coat, but we didn’t know [what they would look like] other than size and skeletal morphology.” Even their appearance as newborn pups was a surprise, with little Romulus and Remus better resembling baby polar bears than our idea of a young gray wolf pup.

Even so, there will undoubtedly be debate to come over how much Romulus, Remus, Khaleesi, and the rest of their intended pack match the ancient creature who died out millennia ago. For starters, it is impossible to directly clone an extinct species. You need a living cell. In the case of these dire wolves, this was created by editing 20 genes in gray wolf cells—a technique Lamm previously told us is part and parcel with natural speciation, albeit in this case it’s been controlled to recreate the lost, desired characteristics of a dire wolf.

Still, Lamm acknowledges there are traits we’ll never be absolutely certain on. For instance, the vocalizations of his dire wolves.

“We do know that if you look at the neck size of our dire wolves compared to normal wolves, they’re bigger, which we know affects the vocalization we hear today. Is it exactly the same vocalization as it was 10,000 years ago? We have no way of knowing what percentage of that’s learned behavior versus what percentage of that’s normal.”

Still, Colossal remains bullish about their research, which used advanced multiplex gene editing to introduce precise genetic edits at 20 loci across 14 genes. More impressive is how these techniques have innovated cloning technology. Whereas cloning previously required extensive tissue samples, including quantities of bone marrow, pieces of skin, and perhaps scraps of an ear, the less intrusive techniques Colossal has pioneered from DNA blood extractions could very well change how we protect endangered species, extinct or otherwise.

Saving the Red Wolf and Beyond

The choice of naming Colossal’s first two dire wolves Romulus and Remus is a telling one. Some debate went on internally over whether one of the two brothers should be dubbed Ghost, in reference to the most famous direwolf on Game of Thrones, but the decision was made to save that for down the road as the pack grows. In the meantime, no single dire wolf in Colossal’s first crop would stand out over another. Instead the names they did settle on would harken back to an ancient, and more wolf-friendly, set of values.

While during the last several thousand years, wolves have regularly been associated with evil and dangerous imagery in the popular (and largely Christian) imagination, there was a time when the creature’s likeness carried different connotations, and it hadn’t been hunted to extinction in Europe and near enough that in North America. In fact, Romulus and Remus were the mythological figures credited with founding Rome, the ancient city that would become an empire—and which was supposedly nurtured by the literal mother’s milk of a she-wolf who fed and raised these two brothers.

“Romulus and Remus were the founders of Rome,” Lamm muses, “so we thought of Romulus and Remus as the founders of the de-extinction movement. They are brothers, so we thought that the mythology made a lot of sense. We thought of them as being a form of ancient wisdom and protectors.”

Like more recent popular fiction such as Game of Thrones, these names also point to a future where the wolf is no longer treated as a monster hunted to the verge of extinction. Which might echo the most impressive implications of this new Romulus and Remus.

“In addition to making the three dire wolves… we actually cloned four red wolves,” Lamm reveals, “which is pretty cool.”

Indeed, one of the reasons the Red Wolf Recovery Program has struggled in North Carolina is due to the lack of biodiversity in the handful of recognized red wolves still living in the wild. However, by embracing the same speciation mindset that allows Lamm to assert his dire wolves are a recreation of the animal that went extinct 10,000 years ago, Colossal researchers partnered with Bridgett vonHoldt, a leading wolf geneticist at Princeton University. Together they used the new cloning techniques derived purely from blood samples to isolate ancient red wolf DNA found in the genetic code of modern-day coyote-red wolf admixed populations located in Louisiana and parts of Texas.

“They have a lot more of the lost red wolf genome data than the ones in the North Carolina population,” Lamm explains. “So we went out and sampled all of them, did a big comparative genomics to prove that, and then we actually took some frozen [DNA] from a founder line of red wolves that’s extinct, that’s dead, and we brought it back using our cloning techniques.”

The Colossal CEO also acknowledged he had a recent meeting with the U.S. Secretary of Interior Doug Burgum and that “if they want me to make a thousand red wolves that are genetically diverse, we could do that for them.” He later adds, “We’ll make all of our technologies available for free for conservation. It’s part of our mandate.”

Since our conversation with Lamm, Burgum issued a statement on X praising de-extinction technology, although perhaps worrisomely for some conservationists, the secretary framed it via his eagerness to minimize the endangered species list.

Burgum wrote, “It’s time to fundamentally change how we think about species conservation. Going forward, we must celebrate removals from the endangered species list — not additions. The only thing we’d like to see go extinct is the need for an endangered species list to exist. We need to continue improving recovery efforts to make that a reality, and the marvel of ‘de-extinction’ technology can help forge a future where populations are never at risk.”

Still, support for improving biodiversity in mammalian wildlife, especially those on the brink of extinction, would be a great legacy for Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi. As for the dire wolves themselves, they currently are living on an undisclosed nature preserve of 2,000 acres with a staff of 10, an animal hospital, and a daily diet of six pounds of meat and three cups of dry feed—a mixture of beef, horse, and deer meat. “They have a good setup right now,” says Lamm. But beyond growing them to a full-sized wolf pack of seven or eight wolves, the Colossal leader is more circumspect about the larger future of this resurrected dire wolf.

“I will tell you over time, there is potential interest right now from some of the Indigenous people groups to put them back ancestrally on their land,” Lamm says. “But once again, a lot of people have a say in that. That’s not our say. So if people want that, then we’d probably pursue that. But as you know, any rewilding program has to be met with a very thoughtful managed rollout.”

For the time being, these wolves still have a 2,000-acre park. Meanwhile their existence points to a better future for their distant American cousins. It’s a promising start for a technology that also aims to aid other species on the edge of extinction like the white rhinoceros, or bring back those humanity wiped out, such as the dodo.

Says Lamm, “I’m pretty proud of what we’re doing, but I do think that de-extinction goes hand in hand with species preservation. It’s just a new tool in our conservation tool belt.”

The post Why the Dire Wolf Returned and How It Could Save the Red Wolf appeared first on Den of Geek.

![Never Too Late [on a Carl Dreyer retrospective]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/dayofwrath2.jpg)

![Prole Models [CITIZEN RUTH & INVENTING THE ABBOTTS]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/citizenruthposter1-209x300.jpg)

![Delta Seat Snaps, Passenger Vomits, Rushed to ER—Ceiling Panels Collapse on Two Other Flights [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/delta-air-lines-ceiling-panel.webp?#)