‘Panic Room’ at 23 – Breaking into David Fincher’s Thriller and Its Novelization

If houses could talk, the one in David Fincher’s Panic Room would have both plenty and very little to say about the Altmans. In this 2002 film, Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart’s characters, a recently divorced mother and her young daughter, ended up only living in their Upper West Side “townstone” for a brief period. […] The post ‘Panic Room’ at 23 – Breaking into David Fincher’s Thriller and Its Novelization appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

If houses could talk, the one in David Fincher’s Panic Room would have both plenty and very little to say about the Altmans. In this 2002 film, Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart’s characters, a recently divorced mother and her young daughter, ended up only living in their Upper West Side “townstone” for a brief period. Nevertheless, their stay was nothing short of eventful. Bizarre and harrowing, these tenants’ domestic nightmare was manifested with technical boldness and performed with dramatic flair. Today, Fincher’s endeavor in popcorn filmmaking isn’t held anywhere in the same regard as his other works, but even so, beneath Panic Room’s polished surface lurks a story teeming with texture.

David Koepp’s script for Panic Room sounds like an update of Lady in a Cage, that 1964 film where Olivia de Havilland’s rich character becomes trapped within her home’s built-in elevator, and is then menaced by aggressive intruders as her neighbors look the other way. It’s a gruesome commentary on the unprotected legal status of women at the time. Koepp, however, was inspired by the uptick in panic rooms — or safe rooms — among the wealthy. Of course, Jodie Foster’s character Meg Altman didn’t go searching for such a safeguard. No, this foreboding add-on in hers and her daughter’s new home was as fortuitous a find as it was integral to their wellbeing.

Panic Room’s cultural timing was punctual. Even though Koepp began penning his screenplay back in 2000, Fincher’s adaptation didn’t hit screens until spring of 2002. By then, there was an undeniable and rampant sense of paranoia hanging in the air that only added to the film’s own tense atmosphere. This is not a story that’s necessarily looking to breed mistrust in a changing and unpredictable world, but most definitely, it benefitted from that post-9/11 climate. Coincidentally, Jodie Foster’s subsequent thriller, Flightplan, also covered the theme of invasion, albeit aggressively.

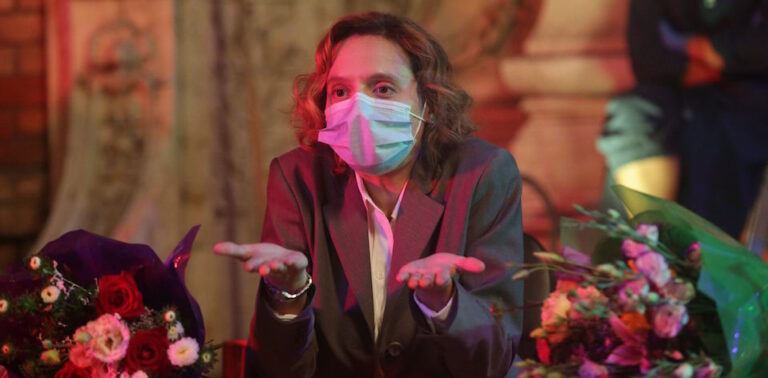

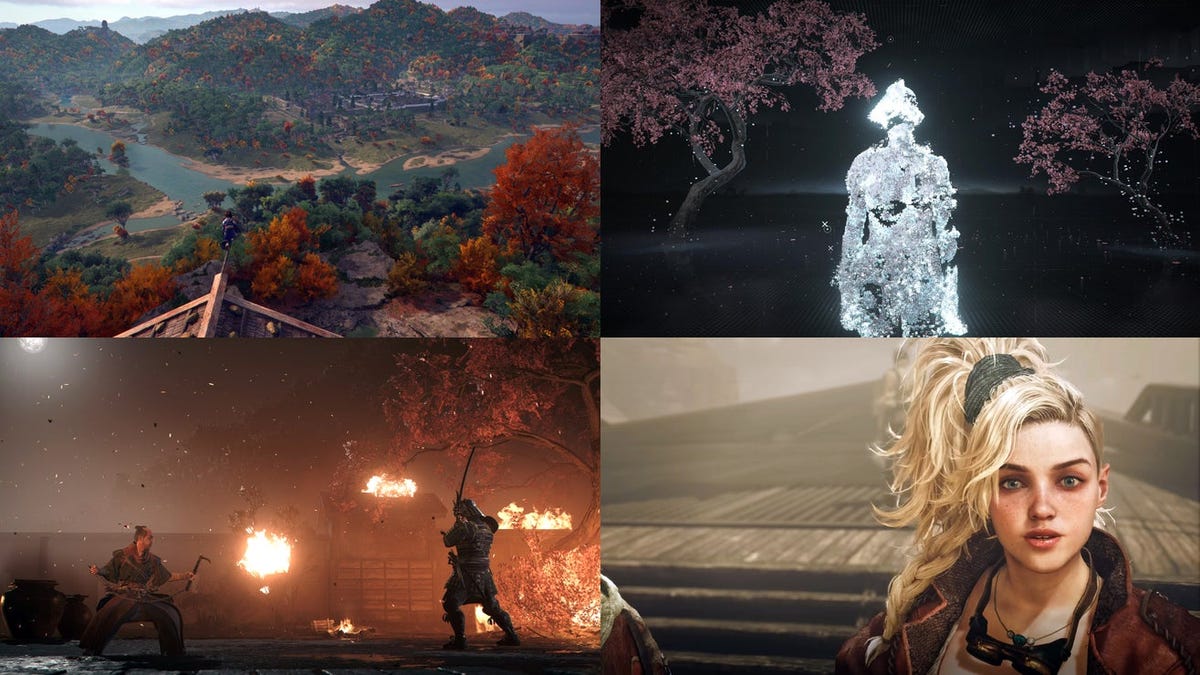

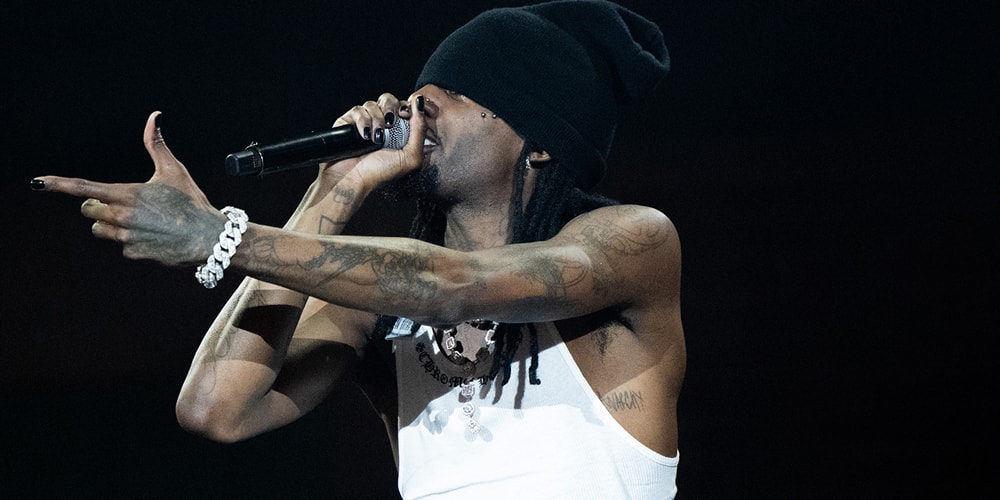

Image: Forest Whitaker and Kristen Stewart in Panic Room (2002).

Home invasion, as a subgenre, is overflowing with tales of forced entry, but Panic Room stands out in how it processes that universal fear. For all that initial boasting heard early on in this film, courtesy of two pushy real estate agents, the titular room doesn’t provide long-lasting relief for Foster’s character once she and her child take refuge. On the contrary, they are now more distressed. In addition to their prowlers refusing to vacate, there are oversights that the two women didn’t think to consider; they are not only trapped in the meantime, they still have no say in how the scenario will play out. So while the technological measures in place may not have literally failed, they never deliver as promised. It’s a rather nasty instance of “results may vary.”

As much as Panic Room wants its characters, along with the audience, to believe money can’t buy them security in the long run, that philosophy means nothing to the story’s antagonists. With the exception of Jared Leto’s Junior, the money-grubbing grandson of the house’s former owner and the panic room’s implementer, the other two burglars would only benefit from their windfall. Forest Whitaker’s Burnham, who helped install the panic room he’s now trying to break into, and Dwight Yoakam’s wildcard character Raoul are each hurting for money. Yet, in their effort to cut to the chase, Fincher and Koepp didn’t delve into personal motives or histories. The Panic Room novelization, on the other hand, has the luxury of time. In its unhurriedness, James Ellison’s literary tie-in fleshes out characters on either side of that impenetrable door.

What could have been mistaken for a throwaway line is actually a bit of crafty foreshadowing. By mentioning the previous owner’s missing fortune and the conflict among his potential inheritors, the thieves’ arrival in the story is less abrupt. Pre-announcing their entrance removes the element of randomness that makes home invasions so dreaded, but Panic Room eventually finds its thrills elsewhere. And in the cinematic version, that morsel of info is just enough to excuse the implausible encounter in store. The novelization behaves likewise, although there is more plot padding around the heist. In particular, author Ellison goes into how Junior teamed up with Burnham and Raoul.

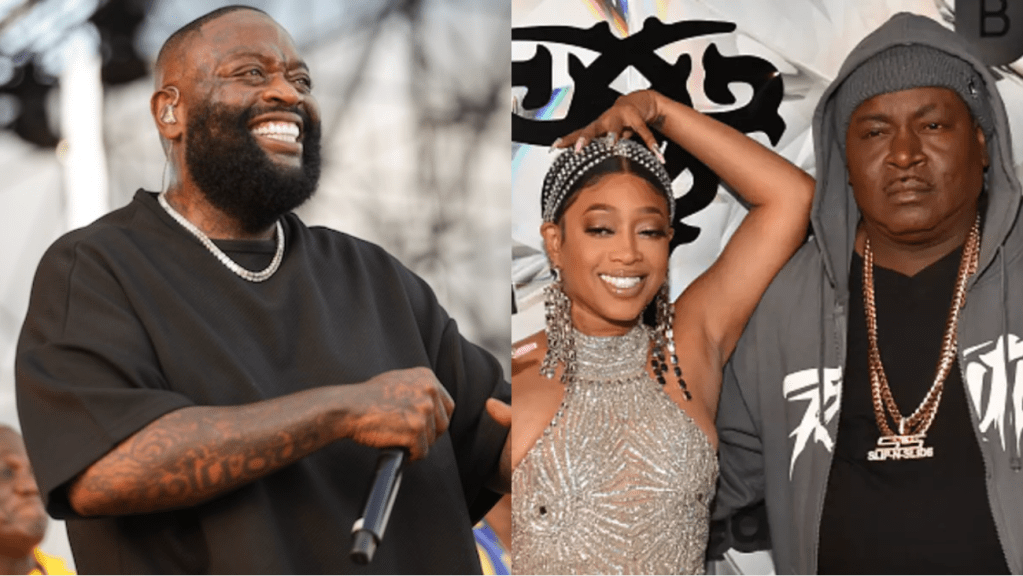

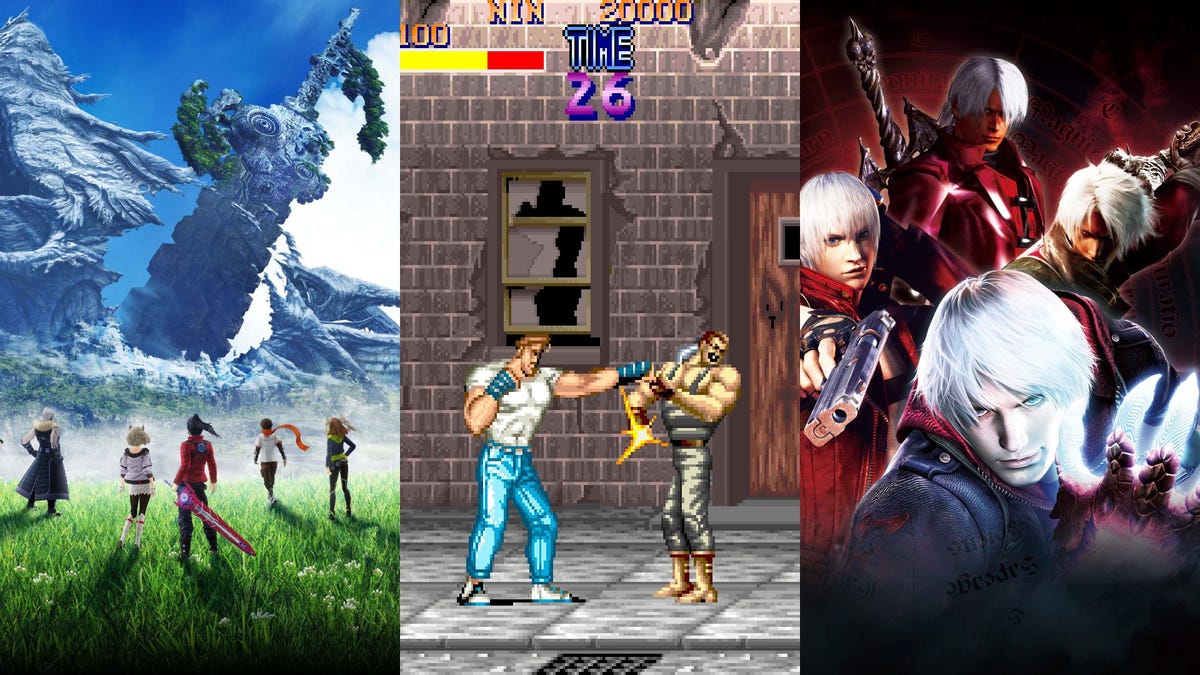

Image: Forest Whitaker and Jared Leto in Panic Room (2002).

In the book, Junior didn’t simply find the man who built the reclusive Sidney Pearlstine’s panic room; he already knew him, seeing as how he and Burnham first crossed paths during the construction, then became reacquainted following the old man’s funeral. As for Raoul, he wasn’t discovered “through some people,” as Junior loosely explained in the film. Raoul is Junior’s drug dealer, fresh out of prison, and endures living with his good-for-nothing mother. Regarding their exact motivations, Burnham wants to clear substantial gambling debts and reconcile with his wife, whereas Raoul craves a clean slate, preferably somewhere tropical. Junior is still an entitled screwup in Ellison’s take, but now he resents his grandfather for being kinder to Burnham — that “staunch left-winger” preferred the company of “a working-class Black man” — than his own family.

Race and class come up in Panic Room even when the film doesn’t explicitly address these topics. The novelization is less inclined to skip the dialogue, even if it’s still done indirectly, and as expected, the author uses Frank Burnham and Raoul Avila to make his points. The matters of systemic poverty and racial discrimination are raised now, thanks to that extra attention paid to both men’s backgrounds.

Jodie Foster took over after Nicole Kidman dropped out, on account of an injury. The change ultimately pushed Fincher to approach the film and its protagonist differently, however, that divorcée-turned-hero is still shown to be quite vulnerable. The novelization runs away with that pathos, emphasizing Meg Altman’s inner battle with herself. Ellison expounded on Koepp’s design and offered a character whose whole life, up until now, has been something of a panic room in itself. The Meg found in the novelization goes through the same situational hurdles as her on-screen counterpart, yet the printed version of her catharsis is granted a bit more emotional oomph. This Meg realizes the weight of her ordeal, and in a way, is thankful for it. Ellison summed it up best by writing: “It had taken her thirty-six years of living, but Meg finally lost her innocence.”

Streamlining Panic Room comes at the cost of some exposition, but the blanks aren’t too hard to fill in, even without reading the novelization. It’s the sort of film where actions speak louder than words. And while the technical components and the high-concept setting evidently received top priority, David Fincher’s eye for detail only enhanced the story of this pulse-pounding and singular thriller.

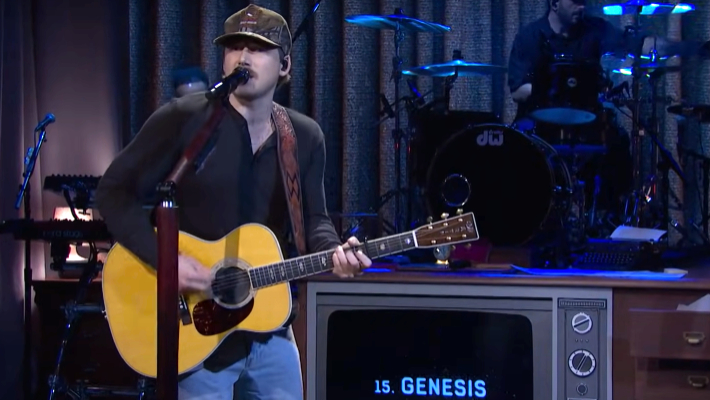

Image: The novelization of Panic Room (2002).

The post ‘Panic Room’ at 23 – Breaking into David Fincher’s Thriller and Its Novelization appeared first on Bloody Disgusting!.

![‘Zombie Army VR’ Shuffles to a May 22 Release; Pre-Orders Open Now [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/zombiearmy.jpg)

![Tubi’s ‘Ex Door Neighbor’ Cleverly Plays on Expectations [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Ex-Door-Neighbor-2025.jpeg)

![Uncovering the True Villains of Gore Verbinski’s ‘The Ring’ [The Lady Killers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-27-at-8.00.32-AM.png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

OSAMU-NAKAMURA.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?#)

![‘Cam’ Puts the “Work” in “Sex Work” [Horror Queers Podcast]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cam-Movie.jpg)