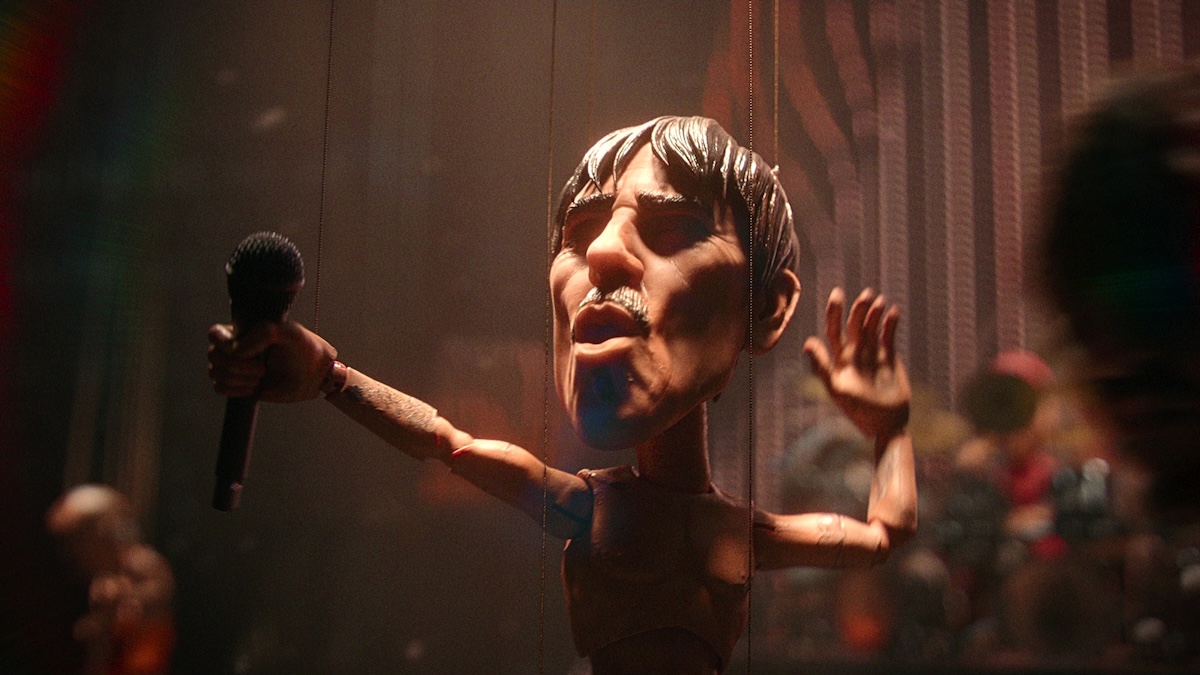

Cannes Review: Enzo is a Queer Coming-of-Age Tale Conveyed with Delicacy

The queer coming-of-age experience is one of great vulnerability: a young person must grapple with the realization they’re becoming different from both past selves and those around them. Robin Campillo’s Enzo, which opened the Directors’ Fortnight sidebar at Cannes, understands the delicacy of such subject matter and paints a fittingly subtle, light-handed portrait of its […] The post Cannes Review: Enzo is a Queer Coming-of-Age Tale Conveyed with Delicacy first appeared on The Film Stage.

The queer coming-of-age experience is one of great vulnerability: a young person must grapple with the realization they’re becoming different from both past selves and those around them. Robin Campillo’s Enzo, which opened the Directors’ Fortnight sidebar at Cannes, understands the delicacy of such subject matter and paints a fittingly subtle, light-handed portrait of its title character. If anything, it suffers from being a bit too lightweight and gives a somewhat unfocused impression initially, until a beautiful third act reveals the mystery and pain of a boy seeking his place in the world.

Enzo is 16. We meet him at a countryside construction site where he mixes concrete and lays bricks under the relentless sun. The work is hard and he seems neither good at it nor motivated to get better. When his boss takes him home to complain about the subpar performance to his parents, we find out Enzo actually comes from money. One look at the gated mansion in which he lives with his white-collar family tells you (and his boss) that Enzo doesn’t have to deal with the hardship of manual labor if he does not wish to; we later learn his father keeps asking he finish his education or do anything else that would bring happiness. But Enzo stays on the job.

Among his all-male co-workers who talk trash and compare notes on girls, there’s Vlad, a Ukrainian immigrant who took Enzo under his wing and shares the horrors of war back home. Through Enzo‘s first hour we see him chill with Vlad, Google the Ukrainian war, rebel against his father’s wishes, labor away to “do something with his hands,” and make out with a girl. While reason is given for the actions of a paradoxical hero who appears to drift through life according to whims, that all changes when Enzo, coming off another confrontation with his father, spends a night at Vlad’s place.

Enzo was initially developed by Palme winner Laurent Cantet (The Class) and completed by Campillo after the former’s death; both filmmakers left their mark on the project. Known for his sharp understanding of young people still trying to figure themselves out, Cantet crafted an intriguing protagonist full of internal struggle and unspoken desires. When movie characters of this age are rarely given deeper consideration than being somebody’s son or daughter, it’s exciting to see one treated with such care. You sense much tenderness and no hint of condescension in this portrayal of a teenager who despite––or perhaps even because of––the comfort and privilege he’s born into, feels trapped in every way.

Campillo’s greatest strength as a director is his humanist instinct to observe. One can tell through his work––the way he shoots actors restaging the Act Up protests in his Grand Prix-winning 120 BPM, or the opening scene of Eastern Boys, where his camera quietly watches a group of scammers go about their work at a Parisian train station––that he’s fascinated by people: the way we act, react, interact. Even when his films do not speak to you thematically, this pure, judgment-free fascination is palpable in every frame; it’s never a chore to observe his subjects alongside him, to spend time with them. Even when there doesn’t seem to be a narrative or emotional focal point during Enzo‘s first hour, it’s also never uninteresting to simply watch and consider this puzzle of a character.

Things pick up substantially after the fateful night at Vlad’s, Enzo forced to face truths about himself and the emotional fallout of his first heartache. With a touch both sensitive and unsentimental, Campillo finishes this story without dramatized sorrow or unrealistic joy, but something more akin to relief––the knowledge that this boy will be okay.

Enzo, like Call Me by Your Name, is about the sexual awakening of a young man. Both take place in sun-kissed locations and end around a phone call that people will remember. Next to Guadagnino’s tsunamic heartbreaker, though, Campillo provides a much lighter affair. It’s commendable that, for once, the gay character in a romance doesn’t have to end up dead or traumatized. It’s also refreshing to see a film address queerness not just within the context of sexuality, but a broader sense of alienation, of not feeling at home in one’s own life. This is a topic that still has endless potential for stories.

Enzo premiered at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

The post Cannes Review: Enzo is a Queer Coming-of-Age Tale Conveyed with Delicacy first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Pieces of Masterpieces [MEDEA & SUNDAY]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/medea.jpg)

![Invitation to the Trance [SLEEPWALK]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/sleepwalk2.png)

![Real Horror Shows [EYES WITHOUT A FACE & THE KINGDOM]](https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/eyes-without-a-face-belgian-poster.jpg)

![The Perfect Actor Wants To Play Batman Villain Clayface [Exclusive]](https://www.slashfilm.com/img/gallery/the-perfect-actor-wants-to-play-batman-villain-clayface-exclusive/l-intro-1747323240.jpg?#)

![‘The Last Class’ Trailer: American Economist Robert Reich Gets The Spotlight In New Education Documentary [Exclusive]](https://cdn.theplaylist.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/15115633/the-last-class-film.jpg)

![Air Traffic Controller Claps Back At United CEO Scott Kirby: ‘You’re The Problem At Newark’ [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/scott-kirby-on-stage.jpg?#)