“There’s No Nostalgia for Me in This Film”: The Legend of Ochi Director Isaiah Saxon on Making His $10 Million Debut Look Bigger Than Life

Making movies is hard. This is not a revelatory observation, though a film like The Legend of Ochi underlines how much most of us take the art of filmmaking for granted. There is so much impossible skill involved in creating worlds and indelible stories told within those worlds. As I said in my review, “The […] The post “There’s No Nostalgia for Me in This Film”: The Legend of Ochi Director Isaiah Saxon on Making His $10 Million Debut Look Bigger Than Life first appeared on The Film Stage.

Making movies is hard. This is not a revelatory observation, though a film like The Legend of Ochi underlines how much most of us take the art of filmmaking for granted. There is so much impossible skill involved in creating worlds and indelible stories told within those worlds.

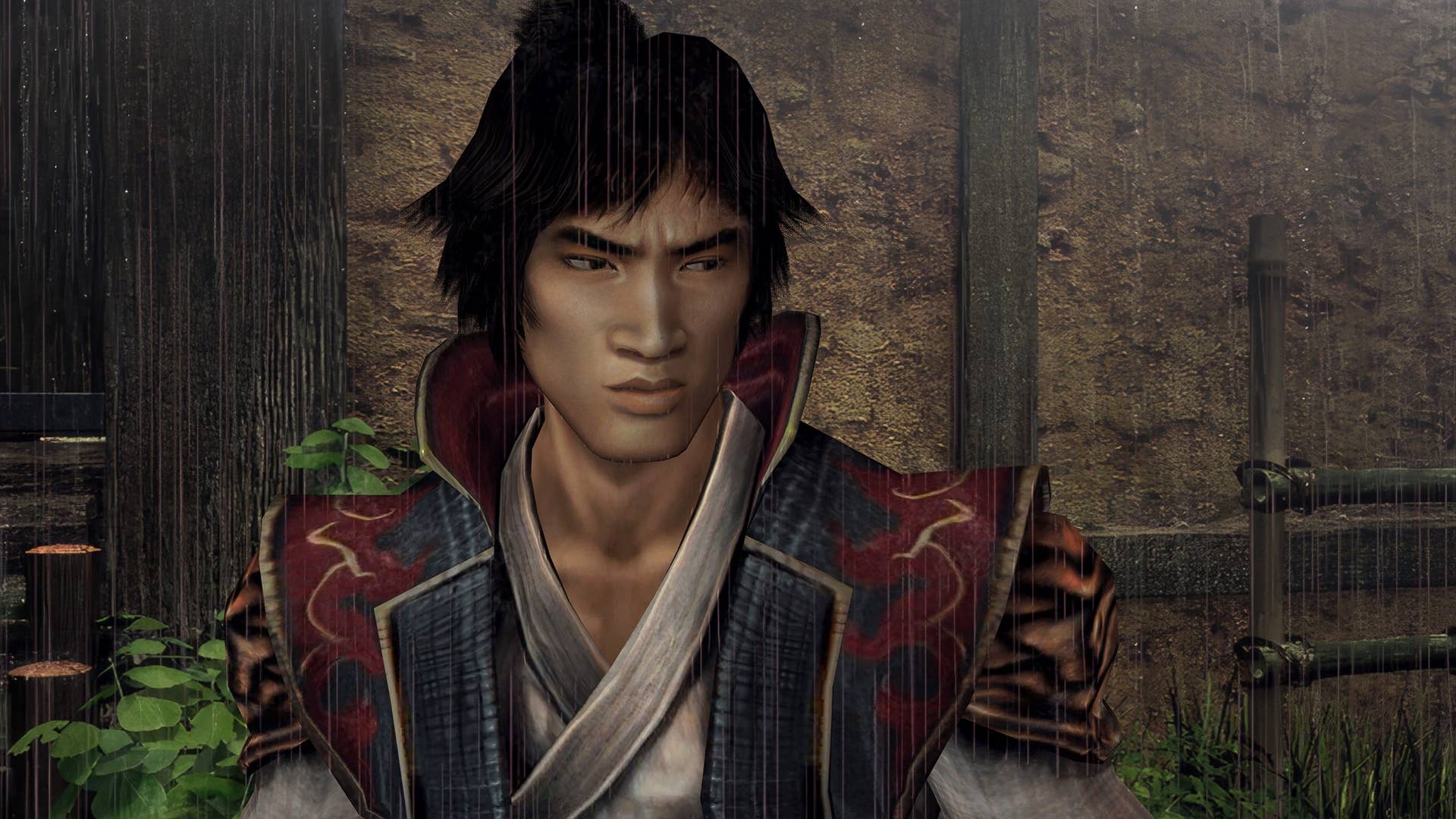

As I said in my review, “The Legend of Ochi, written and directed by Isaiah Saxon, is a lovely adventure built on imagination and skill. It certainly feels like the kind of film that will last a good long while. Short on dialogue and long on style, it tells of the small population in a village on the island of Carpathia: they live in fear of the Ochi, an apparently vicious form of primate haunting the nearby forest. Willem Dafoe plays Maxim, a warrior elder who’s been gifted the village’s children and will train them to fight the dreaded beasts. Among them is Petro (Finn Wolfhard) and Maxim’s own daughter Yuri (Helena Zengel). When Yuri comes across an injured baby ochi, she decides to care for the creature and take it back to its home. To do so, she must run from Maxim and his militaristic ways.”

With the film now in limited release and expanding wide this Friday, I spoke to Saxon about the meticulous process of crafting his feature-directing debut, scouting in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania, cinematic touchpoints, writing the role for Willem Dafoe, and more.

The Film Stage: This is your first feature and you’ve been working on it since 2018, correct?

Isaiah Saxon: [2018]-ish. That’s when I would say I was able to dedicate myself to it full-time. Before that it was kind of thoughts.

Is it a relief now that it’s releasing or is there any sadness [the process] is over?

No sadness whatsoever, no. I mean, I could have been done a long time ago. It’s a tremendous relief. I really didn’t feel that relief until about five days ago, when I first showed it in L.A. to a packed house of friends and family and filmmakers and people I respect. And I saw the film for the first time, because previous to that I’d seen it at Sundance and I was totally blacked-out and anxious. And, previous to that, I was just bug-fixing. I was seeing it every day ten times and finding problems. At that point, you hate your film. So I just saw the film for the first time like everyone else and I was so thrilled. And then I had the same experience a couple of nights ago in New York. Yeah, it’s a joyful thing to find the people that it’s for and hear what it means to them. It’s not for everyone, but it is for some people.

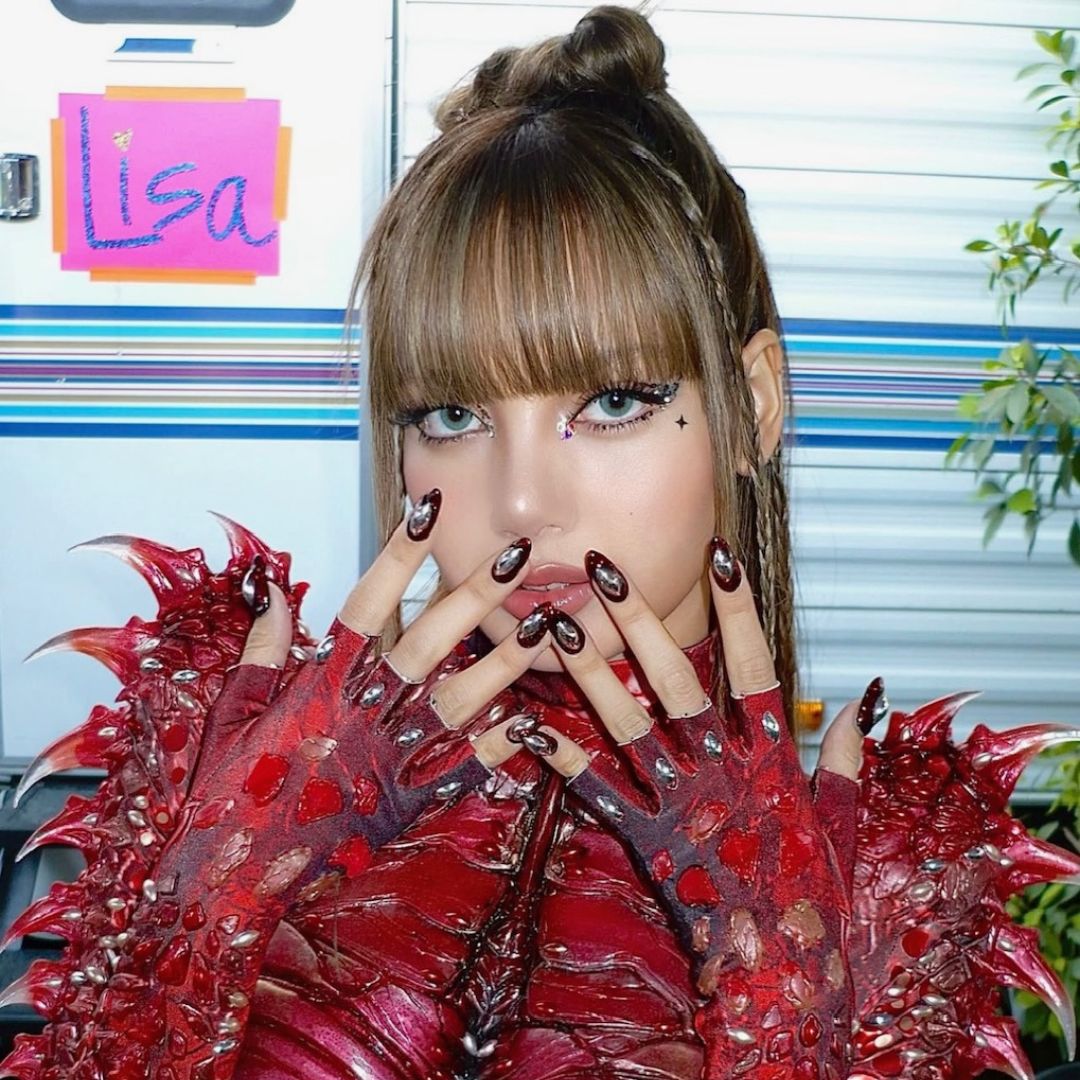

Isiah Saxon on Set

Something that fascinated me: how does scouting a movie like this go? Because you’re in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania?

Yeah, the first bits of money I got for development I immediately spent on prototyping creatures and scouting the Carpathian Mountains of Romania. And drove around for, like, two months––first just with my wife and then second month with my producers and with Castel Films, the Romanian production company. We wanted to look at every little small village through the Carpathians, to find the most mythical, mysterious settings and we would just be often trespassing on people’s land, and they would whistle at us and invite us into their home and feed us the bounty of their wild foraged farm, give us bread and cheese and make us blueberry wine. It’s just an incredible place. It’s where there are still horse-drawn carriages everywhere and people scything their fields by hand. And there’s bears and lynx and wolves everywhere. We called the scout “the adventure scout” because it was a pure adventure.

Blueberry wine, how was that? Was it good?

This is the best alcoholic beverage I’ve had. Not just for its taste, which is amazing, or its texture, which is essentially a bunch of solid blueberries that are just in almost like a syrup of their own fermentation. But the effect, the physical effect of it, is not like any other spirit I’ve had. And I would say it has a minor psychedelic effect and a deeply euphoric effect. So you are just, like, beyond happy. And one of the things you’ll realize if you walk around the Carpathian Mountains is the twinkle in everyone’s eye is alcohol-related.

It sounds like a lovely place! You’ve done a lot of animation in every manner. What I’m curious about is that with animation, you technically have full control to make whatever is in your mind. Whereas now you are making a live-action movie with all the variables. Was that hard to transition to?

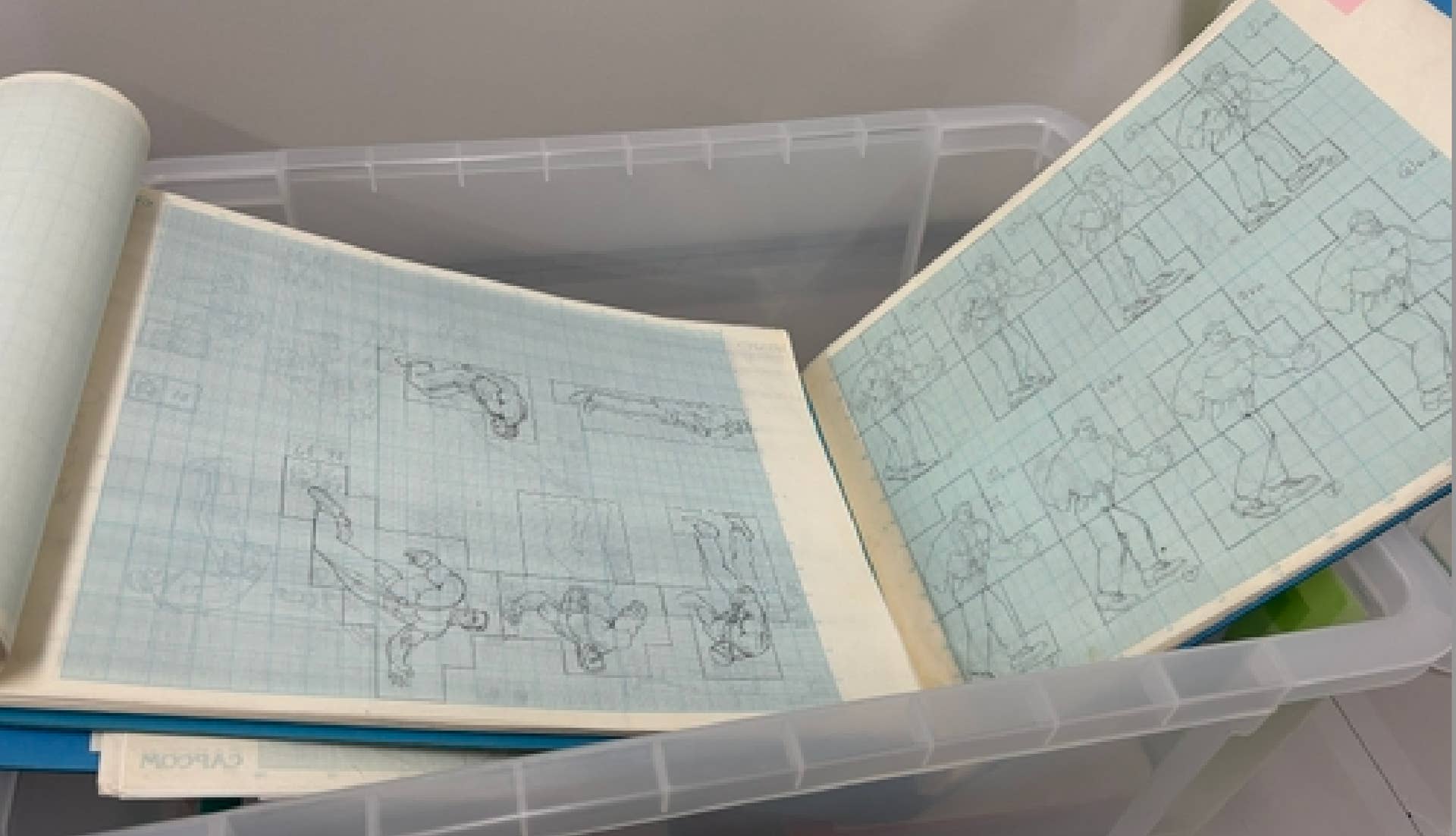

Well, I got my start in live-action. So my trajectory was: I drew a lot of pictures as a kid; I started sculpting stuff and building stuff; and then I realized I could make films that use that at its center, just following my fun of what I wanted to be doing with my hands. So when I started making films, it was always music videos and shorts that were live-action, but I would have puppets or creatures or prosthetics and painted backdrops and sets. It’s so challenging, but it’s so intoxicating and fun, doing stuff with your friends and building stuff. By the time I had finished the Björk “Wanderlust” video, I was like 24, 25 and I had just completely exhausted myself doing this. It’s so hard, this approach.

And so my route into animation was actually to just take a break. It’s chill to sit there and tweak things on a computer and there’s not a gun to your head and Murphy’s Law of the realm of physics stopping you at every turn, making your shooting day and all the challenges. So animation is, for me, like a lifestyle choice. But then it also let me level-up all these skills over those years of making animation, of hiring small teams of visual-effects artists and CG people and learning the software myself and learning how to make really compelling concept art in Photoshop and just leveling-up my digital skills so that when it came time to do this movie, I could leverage all of the skills and make something that was $10,000,000 look bigger than it is.

In terms of the experience of shooting this: this was, like, the most brutal eight weeks of my life. This was absolutely exhausting and painful and excruciatingly stressful. And then we get three years of post-production to very slowly make it right and to do 200 matte paintings and take these incredible Carpathian locations, and if the weather wasn’t right, paint in the fog, paint in the clouds––get everything to feel the way that I needed it to feel, to tell the story, to keep the mood, to keep the tone.

What did you shoot on?

So the idea was we want it to feel like the movies we like feel, which are [Carroll Ballard]’s The Black Stallion ––

The one you mentioned recently in an interview, and I kept thinking about, is Quest for Fire.

Oh, fuck yeah, bro!

The simplicity of narrative in your story…

Yeah, it’s non-verbal storytelling…

Exactly.

It’s about ancient forms of communication that are deeper than words. Quest for Fire is where our primate motion choreographer, Peter Elliott, got his start. As a young man he was one of the great ape suits, and he tells an incredible story where they had some elephants from the London Zoo dressed up as wooly mammoths. And he and other apes are supposed to get out of the way and scatter as there’s a mammoth stampede, and there’s a take in the film in which these elephants, who are not very direct-able, they start running, and the apes are supposed to scatter on all fours, of course––they’re quadrupedal––and you just see all the performers in ape suits go upright and start to run, including him.

[Both laugh]

But yeah: we could spend the rest of the interview just talking about Peter Elliott, who’s the most interesting man alive. He’s been in the ape suit for every primate film, from [Quest for Fire] to the [Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes] to Gorillas in the Mist and Congo. He got in the ape suit for our movie, but really he was the primate motion choreographer. He’s in his 60s now so he’s making all of our puppeteers and our suit performers dial in to real primate behavior.

Anyways, the look of the film: the reference points being our favorite cinematography, like Black Stallion and There Will Be Blood. Things which are obviously shot on film, have natural lighting, have high-contrast silhouettes, and have this balance between grand cinematic scale and lived-in, grounded, dirty specificity and they’re small and subtle and big at the same time. We knew because of the approach––that would include matte paintings and even 3D environments towards the end of the film––that the film aesthetic would need to come at the end. I don’t want it to start dirty. We shot on large format ALEXA, our acquisition medium, but with 1930s glass, the original Baltars, which were the first U.S.-produced lenses. And then, at the very end, we print to film, after all the matte paintings and everything, we print film stock and rescan it. And that’s the look of the movie.

Wow, that’s interesting. The company you have with Daren Rabinovitch and Sean Hellfritsch, Encyclopedia Pictura, you guys are so essential to the early-00s music video aesthetic. If you’re thinking about Panda Bear, Björk, that feels classical now. Thinking of your film, Labyrinth probably comes to mind, Return to Oz, Quest for Fire, these movies from the ‘80s. What I find fascinating about your film is that it is this dual nostalgia thing: it’s like these tricks, these processes you learned making music videos 20 years ago, loving movies 20 years before that, and it’s all in the movie. And I don’t think there’s another movie like that yet, combining all of these things, and I was trying to think of another example of what would be like that. I don’t know if there is another. Right?

I don’t know. That’s for other people to say. I mean, maybe Spike Jonze was trying to do that with Where the Wild Things Are or Everything Everywhere All at Once––they have a similar approach. Those guys are my friends.

Right, those are two good examples. It’s an interesting subset of movies. You and I being similar ages, I feel like I’m seeing my whole life.

Yeah, I see what you mean. In some ways, this is equal-parts like that moment in time where the [Michel] Gondry, [Chris] Cunningham, Spike [Jonze] DVDs came and were all like, “Fuck, we need to make magic tricks out of movies,” And then also the previous generation of magic tricks that were happening in the ’80s practical effects films. I mean, look, the thing is: there’s no nostalgia for me in this film. I’m not going, “What films meant to me when I was a kid.” Like, I didn’t see E.T. until I was 25; I’ve never seen Gremlins. But yeah: Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches, that deeply shaped me when I was in fifth grade.

But also the films of Powell and Pressburger shaped me and Kwaidan shaped me and Ugetsu shaped me and Miyazaki shaped me and, more recently, PTA. The sea of influences is kind of infinite. And it’s also just in paintings and sculpture and art. And so it’s funny for people to be like, “This must be pulling from The Dark Crystal and The NeverEnding Story.” I’m like, “I don’t think I even saw those movies as a kid. And then, when I did, I was mostly like, “These are narratively weak, but aesthetically gorgeous.” So they’re just not influences whatsoever, but they’re other people’s touchpoints for when the last time they felt some feeling.

Even the matte painting of it all. You said you did over 200?

I did over 200, but I mean––I haven’t sat down to count them all. There were 700 VFX shots, so at least 200 of those, I was providing the element for my compositing team to build around.

You talk about Powell and Pressburger and you think about Black Narcissus, my God. What’s so great about a film like this getting a proper release, to your point, the 16-year-old, 14-, 13-year-old kid who sees this, it will be such a springboard into so many other imaginative things.

I hope so.

When you are casting this, you have the most interesting faces. You’ve got Dafoe, Watson, Finn Wolfhard, obviously Helena Zengel. Is it just an obvious thing when you’re casting, “I just want people who look like they could only be there”?

I’m sure the look is a part of it, but it’s also just who the human is. What are their capabilities and their particular skills? With Willem, early on in the writing I’m like, “It can really only be Willem.” And then it’s the Willem I can conjure and bring into the writing room with me, who is writing the movie, who is writing all of this stuff because I know he has a superpower. You know, he can be devastatingly scary and severe and then vulnerable and cute and adorable and kind of a sad sack. And he can kind of waver between and articulate between like nobody else. So nobody else could play the role. And I had kind of written myself into a corner because that’s what I wrote, because I knew he could do that, and that’s what I wanted to express with him. Then with Emily Watson, it’s the same like. Maybe Björk could have done it, but Emily Watson and Björk, there’s like an internal heart of gold. You can’t act that.

But also like a hardness, though.

Yeah, the severity of nature is in them as well.

Right, exactly. That’s what makes it harder because it’s like you see her and you’re like, “Oh, thank goodness.” But then within five minutes you’re like, “Oh well, okay.” Specifically, Dafoe and Watson, they really represent the idea of researcher-protector and warrior-protector being this opposites-attract thing. That is common in life, right?

As a plausible couple, 100%. You know, you see the wedding picture in the film and I think that’s the most believable wedding picture I’ve ever seen.

Yeah, there is some weird elemental, like: she would be attracted to this guy who would have a curiosity that he would then betray.

I’m glad you’re doing the work to think about this stuff because, you know, I gotta say: the one frustration of hearing people’s responses––the people who, I think, as soon as they have it in their head, “This is a fantasy-adventure movie that plays on the nostalgia kid movies.” That’s what they think it is. They think that’s more of, like, a lean-back experience for kids and that it’s going to come to them. It’s going to say all the things it needs to say and it’s going to do all the things. And you just sit back and it’ll come to you.

But that’s not what I’m interested in in filmmaking. I really want to say as little explicitly as I can, but to give you all the breadcrumbs to do the work, to lean in, to create the meaning yourself. That’s not how this genre normally operates. I’m hoping there’s just deep subtlety. And if you are tracking all the things and you’re curious and doing work, then it’s a complete work. But it’s not a complete work unless you complete it. But that’s the thrill of watching, to me. My favorite work is, like, Paris, Texas. You have to do so much work to make that emotionally sound. And it’s the most emotionally sound film, but it demands so much of you. But that’s the thrill. That’s the whole thrill of the chase.

Yeah, that’s a good reference. It’s well-said. The Legend of Ochi does toe the line between scary but with an inviting nature to it as well. As we wrap up, I have two young boys, and I’ve been thinking: what age could they watch? My oldest is four years old.

They can handle it! My producer has a three-and-a-half-year-old.

You think so?

I can tell you have an advanced four-year-old because of who you are, so they can handle it.

The Legend of Ochi is now in limited release and expands this Friday, April 25.

The post “There’s No Nostalgia for Me in This Film”: The Legend of Ochi Director Isaiah Saxon on Making His $10 Million Debut Look Bigger Than Life first appeared on The Film Stage.

![Fear Has No Cure on ‘The Remedy’ Poster [Exclusive]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/TheRemedy-poster-2.jpg)

![Mouse Invades United Club at LaGuardia on the Eve of $1,400 Fee Hike [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/united-club-lga.jpg?#)

![Caught on Video: “He Busted Through!” Frontier Airlines Passenger Storms Closed Las Vegas Gate [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-20-140707.png?#)

-All-will-be-revealed-00-35-05.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png)

![[Podcast] Unlocking Innovation: How Play & Creativity Drive Success with Melissa Dinwiddie](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/melissa-dinwiddie-youtube.png)