Lili Reinhart’s ‘American Sweatshop’ Exposes Social Media’s Dark Side

Merle Cooper Her latest film, the SXSW thriller 'American Sweatshop,' inspired her to get rid of the app on her phone: "It's just a toxic, shitty place."

For Lili Reinhart, who rose to fame on the CW’s long-running teen drama, Riverdale, existing online was always the norm. Even as her peers – Maya Hawke and, more recently, Scarlett Johansson – have spoken out about the part follower counts play in franchise casting or getting indie projects off the ground, she’s always had a realistic view of social media and how useful it can be. Would it be nice, less exhausting even, to be someone like Emma Stone or Jennifer Lawrence, actors who don’t have a platform where people can peek at intimate pieces of their life? Sure.

“But I think I was just born and raised in the era where you had it and didn’t think otherwise,” Reinhart tells UPROXX. “I joined Instagram when I was 16. I think in hindsight, I would still choose to have it because it’s led to a lot of connections and a lot of good, but there is a weird balance there.”

She’s thinking more about that balance lately thanks to her recent indie project, a thriller titled American Sweatshop that premiered at SXSW over the weekend. In it, Reinhart plays Daisy, a twenty-something young woman working as a social media content moderator who is forced to witness the very worst of human nature, one flagged media post at a time. Directed by Uta Briesewitz (Severance, Black Mirror), the film argues that, yes, the internet is a cesspool, but it could be worse. It could exist without these real-life digital sin-eaters who wade through the amoral muck so we can enjoy our doom-scrolling without so much post traumatic stress.

Even before the film, Reinhart was rethinking her social media habits. She recently launched her own skincare brand, Personal Day, and her own production company, an entrepreneurial pivot that’s changed her persona online.

“I had to lean into being a founder and an influencer more than an actor online. And that’s been weird,” she explains. “I don’t love being more of a personality online than an acting figure, but it’s sort of what I’ve had to do to cultivate a business that I founded. So sometimes you just got to roll with the punches and know that it’s for the sake of a company or the sake of a film.”

Despite that, there’s one app she’s happy to have deleted from her phone: Twitter.

“[X] is just a toxic, shitty place,” she says.

Though American Sweatshop doesn’t explicitly name any social media platforms, Briesewitz and Reinhart drew inspiration from real-life stories of Facebook, YouTube, and X content moderators who toil long hours in warehouse-sized cubicles as they sift through the junk their Silicon Valley counterparts can’t be bothered to clean up. From German documentaries and peer-reviewed studies to investigative reports and multi-million dollar class action lawsuits, the pair didn’t have to dig too hard to realize the human cost of the internet’s dirtiest secret. A simple search can turn up dozens of stories on minimum-wage workers in places like Texas, California, and Florida (where Briesewitz’s film is based) who review millions of disturbing images, videos, and instances of hate speech – flagged content called “tickets” – per day. According to a report by NYU Stern, just one Facebook moderator examines 200 posts in an 8-hour shift or one post every 2.5 minutes. Graphic violence, pornography, and conspiracy theories can make up the bulk of that content. No wonder then that so many who take on the job begin suffering panic attacks, anxiety spikes, nightmares, insomnia, depression, and PTSD just months after onboarding.

“These people are suffering,” Briesewitz says.

For Daisy, the darkness begins to creep in after a particular ticket, one involving an off-camera act of sexual violence, causes her to faint on the warehouse floor. Most of Briesewitz’s film hinges on Reinhart’s physical reactions to content the audience is (thankfully) shielded from. She trusts viewers can draw conclusions without any spoonfeeding. Muffled moans might be porn, screams and gunshots might allude to an act of mass violence and we make educated guesses at the outcome based on Reinhart’s expressions. She’s the film’s emotional fulcrum.

“It’s not gore porn,” Reinhart says of the decision to keep some of the film’s violence vague. “It’s not something that an audience will walk away feeling like they can’t get those images out of their head. We don’t want to traumatize an audience by talking about the trauma of what’s online. Ultimately, the movie’s about how these things affect us as human beings.”

That’s why, halfway through the film, once the psychological slog of Daisy’s every day makes its impact, Briesewitz flips the script, turning her drama into a thrilling experiment in back swamp noir that sees Reinhart risking it all to track down the man in the video that’s started to haunt her waking hours.

“Seeing this video changes her,” Briesewitz says. “She talks about it, how she sees a lot of violent videos and it makes her want to be violent. It’s almost like downloading these images – everything that she sees and takes in – is changing her DNA, changing who she is.”

And this is where Florida comes in.

While most of the movie was shot abroad, Briesewitz clung to the idea of setting her film in the panhandle for two reasons. First and foremost, there’s something primal and wild about the place, at least according to the German filmmaker: “Let’s face it, Florida is just a weird place.”

But, as Briesewitz was researching stories of content moderators in the states, a wetlands mascot caught her eye.

“The gator was part of a magazine article about places like this,” Briesewitz says of the massive reptile in the film that floats in a nearby pond where Daisy spends her smoke breaks. “Workers were talking about how they could look out the window and they would see this alligator that had moved in into a little body of water near the parking lot and nobody would really fully acknowledge the danger of him; everybody would just go back to their work. That is a beautiful metaphor for it all. The danger of saying, “I’m not fully acknowledging and just living with it. It’s all okay and it’s normal.’”

Reinhart hopes her film will make audiences reconsider their chronically online status in the same way she has. Moderation is, after all, the whole point.

“As much good as there is from an online community where people can gather and share experiences and stories that are accessible to anybody, I think the spread of misinformation is so much more harmful,” she says. “I think the bad unfortunately outweighs the good. And I try to tap into the good by being more involved in the good communities. But I think as we’ve seen, if there’s going to be a community of people lifting each other up, there’s going to be the opposite. And unfortunately, I think that community is a thousand times larger and more aggressive and violent. And so that has bred a lot of fear and hate and violence, especially in America. I hope we reach a point one day where we can all collectively say, ‘Let’s be done.’”

![‘Silent Hill f’ Announced for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series and PC; New Trailer and Details Revealed [Watch]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/silenthillf-1.jpg)

![Final Pre-Sale Campaign Launched for ‘TerrorBytes: The Evolution of Horror Gaming’ [Trailer]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/terrorbyteslogo.jpg)

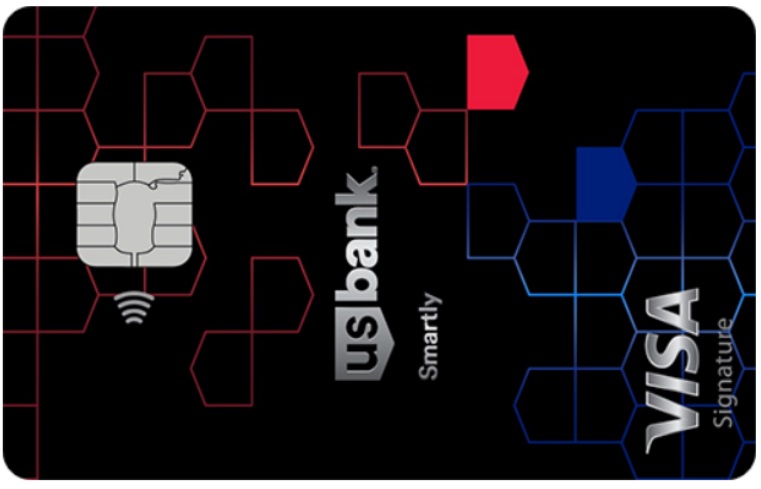

![[FINAL WEEK] Platinum Status And 170,000 Points: IHG’s New $99 Credit Card Offer Worth Getting And Keeping](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMG_3311.jpg?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![[Podcast] Should Brands Get Political? The Risks & Rewards of Taking a Stand with Jeroen Reuven](https://justcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jeroen-reuven-youtube.png)